by John David: Can you begin by telling us something about Ramana Maharshi’s early life? How he woke up as a young boy in Madurai…

David Godman: His given name was Venkataraman and he was born into a family of South Indian brahmins in Tiruchuzhi, a small town in Tamil Nadu. He came from a pious, middle-class family. His father, Sundaram Iyer, was, by profession, an ‘uncertified pleader’. He represented people in legal matters, but he had no acknowledged qualifications to practice as a lawyer. Despite this handicap, he seemed to have a good practice, and he was well respected in his community.

Venkataraman had a normal childhood that showed no signs of future greatness. He was good at sports, lazy at school, indulged in an average amount of mischief, and exhibited little interest in religious matters. He did, though, have a few unusual traits. When he slept, he went into such a deep state of unconsciousness, his friends could physically assault him without waking him up. He also had an extraordinary amount of luck. In team games, whichever side he played for always won. This earned him the nickname ‘Tangakai’, which means ‘golden hand’. It is a title given to people who exhibit a far-above-average amount of good fortune. Venkataraman also had a natural talent for the intricacies of literary Tamil. In his early teens he knew enough to correct his Tamil school teacher if he made any mistakes.

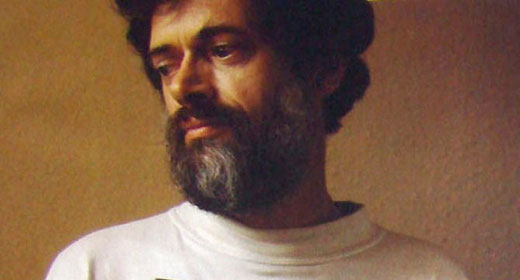

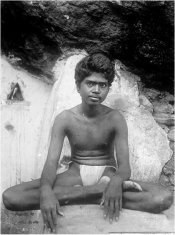

Sri Ramana Maharshi, the earliest photo taken in 1902

His father died when he was twelve and the family moved to Madurai, a city in southern Tamil Nadu. Sometime in 1896, when he was sixteen years of age, he had a remarkable spiritual awakening. He was sitting in his uncle’s house when the thought occurred to him that he was about to die. He became afraid, but instead of panicking he lay down on the ground and began to analyze what was happening. He began to investigate what constituted death: what would die and what would survive that death. He spontaneously initiated a process of self-enquiry that culminated, within a few minutes, in his own permanent awakening.

In one of his rare written comments on this process he wrote: ‘Enquiring within ”Who is the seer?” I saw the seer disappear leaving That alone which stands forever. No thought arose to say ”I saw”. How then could the thought arise to say ”I did not see”.’ In those few moments his individual identity disappeared and was replaced by a full awareness of the Self. That experience, that awareness, remained with him for the rest of his life. He had no need to do any more practice or meditation because this death-experience left him in a state of complete and final liberation. This is something very rare in the spiritual world: that someone who had no interest in the spiritual life should, within the space of a few minutes, and without any effort or prior practice, reach a state that other seekers spend lifetimes trying to attain.

I say ‘without effort’ because this re-enactment of death and the subsequent self-enquiry seemed to be something that happened to him, rather than something he did. When he described this event for his Telugu biographer, the pronoun ‘I’ never appeared. He said, ‘The body lay on the ground, the limbs stretched themselves out,’ and so on. That particular description really leaves the reader with the feeling that this event was utterly impersonal. Some power took over the boy Venkataraman, made him lie on the floor and finally made him understand that death is for the body and for the sense of individuality, and that it cannot touch the underlying reality in which they both appear.

When the boy Venkataraman got up, he was a fully enlightened sage, but he had no cultural or spiritual context to evaluate properly what had happened to him. He had read some biographies of ancient Tamil saints and he had attended many temple rituals, but none of this seemed to relate to the new state that he found himself in.

jd: What was his first reaction? What did he think had happened to him?

DG: Years later, when he was recollecting this experience he said that he thought at the time that he had caught some strange disease. However, he thought that it was such a nice disease, he hoped he wouldn’t recover from it. At one time, soon after the experience, he also speculated that he might have been possessed. When he discussed the events with Narasimhaswami, his first English biographer, he repeatedly used the Tamil word avesam, which means possession by a spirit, to describe his initial reactions to the event.

jd: Did he discuss it with anyone? Did he try to find out what had happened to him?

DG: Venkataraman told no one in his family what had happened to him. He tried to carry on as if nothing unusual had occurred. He continued to attend school and kept up a veneer of normality for his family, but as the weeks went by he found it harder and harder to keep up this façade because he was pulled inside more and more. At the end of August 1896 he fell into a deep state of absorption in the Self when he should have been writing out a text he had been given as a punishment for not doing his schoolwork properly.

His brother scornfully said, ‘What is the use of all this for one like this?’ meaning, ‘What use is family life for someone spends all his time behaving like a yogi?’

The justice of the remark struck Venkataraman, making him decide to leave home forever. The following day he left, without telling anyone where he was going, or what had happened to him. He merely left a note saying that he was off on a ‘virtuous enterprise’ and that no money should be spent searching for him. His destination was Arunachala, a major pilgrimage center a few hundred miles to the north. In his note to his family he wrote ‘I have, in search of my father and in obedience to his command, started from here’. His father was Arunachala, and in abandoning his home and family he was following an internal summons from the mountain of Arunachala.

He had an adventurous trip to Tiruvannamalai, taking three days for a journey that, with better information, he could have completed in less than a day. He arrived on September 1st 1896 and spent the rest of his life here.

jd: For someone who doesn’t know much about Arunachala, could you paint a picture of what this place is like, and what it signifies? Perhaps also say what it would have been like when Ramana Maharshi first arrived.

DG: The town of Tiruvannamalai, with its associated mountain, Arunachala, has always been a major pilgrimage center. The town’s heart and soul haven’t changed that much in recent times despite the presence of auto-rickshaws, TV aerials and a vast expanse of suburbs. The basic culture and way of life of people in Tiruvannamalai have probably been the same for centuries. Marco Polo came to Tamil Nadu in the 1200s on his way home from China. His description of what people were doing and how they were living are very recognizable to people who live here today.

Tiruvannamalai has one of the principal Siva-lingam temples in South India. There are five temples, each corresponding to one of the elements: earth, water, fire, air and space. Tiruvannamalai is the fire lingam.

The earliest records of this place go back to about AD 500, at which point it’s already famous. Saints were touring around Tamil Nadu in those days, praising Arunachala as the place where Siva resides, and recommending everyone to go there. Before that, there aren’t really any records because local people didn’t start writing things down or making stone buildings that would last.

There’s a much older tradition that suddenly appears in the historical record about 1,500 years ago, simply because a major cultural change resulted in people making proper monuments and writing things down. I would say that Ramana Maharshi was, in this historical context, the most recent and probably the most famous representative of a whole stream of extraordinary saints who have been drawn by the power of this place for at least, I would guess, 2000 years.

jd: When was the big temple built?

DG: It grew in layers, in squares, from the inside out. Once upon a time there was probably a shrine about the size of a small room. You can date all these things because the walls of temples here are public record offices. Whenever a king wins a war with his neighbor, he gets someone to chisel the fact on the side of a temple wall. Or, if he gives 500 acres to someone he likes, that fact also is chiseled on the temple wall. That’s where you go to see who’s winning the battles and what the king is giving away, and to whom.

The earliest inscriptions, they’re called epigraphs, on the inner shrine date from the ninth century, so that’s probably the time it was built. Progressively, up to about the 1600s the temple got bigger and bigger and bigger. It reached its current dimensions in the seventeenth century. For people who have never seen this building, I should say that it’s huge. I would guess that each of the four sides is about 200 yards long, and the main tower is over 200 feet high.

jd: And that’s where Bhagavan came to when he arrived?

DG: When Bhagavan was very young he intuitively knew that Arunachala signified God in some way. In one of his verses he wrote, ‘From my unthinking childhood the immensity of Arunachala had shone in my awareness’. He didn’t know then that it was a place that he could go to; he just had this association with the word Arunachala. He felt, ‘this is the holiest place, this is the holiest state, this is God himself’. He was in awe of Arunachala and what it represented without ever really understanding that it was a pilgrimage place that he could actually go to. It wasn’t until he was a teenager that one of his relatives actually came back from here and said, ‘I’ve been to Arunachala’. Bhagavan said it was an anti-climax. Before, he had imagined it to be some great heavenly realm that holy, enlightened people went to when they died. To find he could go there on a train was a bit of a let down.

His first reaction to the word Arunachala was absolute awe. Later there was a brief period of anticlimax when he realized it was just a place on the map. Later still, after his enlightenment experience, he understood that it was the power of Arunachala that had precipitated the experience and pulled him physically to this place.

The verse I just quoted from chronicles the early stages of his relationship with the mountain:

Look, there [Arunachala] stands as if insentient. Mysterious is the way it works, beyond all human understanding. From my unthinking childhood, the immensity of Arunachala had shone in my awareness, but even when I learned from someone that it was only Tiruvannamalai, I did not realize its meaning. When it stilled my mind and drew me to itself and I came near, I saw that it was stillness absolute.

The last line contains a very nice pun. Achala is Sanskrit for ‘mountain’ and it also means ‘absolute stillness’. On one level this poem is describing Bhagavan’s physical pilgrimage to Tiruvannamalai, but in another sense he is talking about his mind going back into the heart and becoming totally silent and still.

When he arrived, and this is something you won’t find in any of the standard biographies, he said he stood in front of the temple. It was closed at the time, but all the doors, right through to the innermost shrine, spontaneously opened for him. He walked straight in, went up to the lingam and hugged it.

He didn’t really want this version of events publicized for two reasons. First, he didn’t like letting people know that miracles were happening around him. When such events happened, he tried to play them down. Second, he knew that the temple priests would get very upset if they found out that he had touched theirlingam. Even though he was a brahmin, the temple priests would take his act to be a contaminating one, and they would have had to order a special elaborate puja to reconsecrate the lingam. Not wanting to upset them, he kept quiet.

jd: Yes, we’ve just come from the temple just now and there’s a huge lock on the door.

DG: Yes. Ordinarily, no outsider can get anywhere near the lingam. Looking after it is a hereditary profession. No one from outside this lineage is allowed over the metal bar that is about ten feet in front of the lingam.

There is another interesting aspect to this story. From the moment of his enlightenment in Madurai there was a strong burning sensation in Bhagavan’s body that only went away when he hugged the lingam. Touching the lingam grounded or dissipated the energy. The lingam in the temple is not just a representation of Arunachala. It is held to be Arunachala himself. The hugging of the lingam was the final act of physical union between Bhagavan and his Guru, Arunachala.

I have not read of any other visit by Bhagavan to the inner shrine. This may have been the only time he went. One visit was enough to transact this particular piece of business.

Bhagavan always loved the physical form of the mountain Arunachala and spent as much time as he could on its slopes, but his business with the templelingam was completed within a few minutes of his arrival in 1896.

jd: Am I right in thinking that from then on he pretty much stayed within the confines of the temple?

DG: After this dramatic arrival, he stayed in various parts of the temple for several months. The day he arrived he threw away all his money into a local tank; he shaved his head, which is a sign of physical renunciation; he threw away all his clothes and he just sat quietly, often in a deep samadhi in which he was completely unaware of his body or his surroundings. It was his destiny to stay alive and become a great teacher, so people force-fed him and looked after him in other ways. Without that particular destiny to fulfill, he would have probably given up his body or died from physical neglect. For the first three or four years he was here, he was mostly unaware of anything around him. He rarely ate, and at one time his body started to rot. Portions of his legs became open, festering sores, but he didn’t even notice.

jd: This is when he was sitting down in that kind of basement?

DG: Yes. have you been there? It’s called Patala Lingam. He was in that place for about six weeks. At the end of that period he had to be physically carried out and cleaned up.

In his early years here he said that he would open his eyes, without knowing how long he had been oblivious to the world. He would stand up and try to take a few steps. If his legs were reasonably strong, he would infer that he had been unaware of his body for a relatively short period – perhaps a day or two. If his legs buckled when he stood to walk, he would realize that he had probably been in a deep samadhi for many days, possibly weeks. Sometimes he would open his eyes and discover that he was not in the place where he had sat when he closed his eyes. He had no recollection of his body moving from one place to another within one of the temple mantapams.

jd: Did anyone recognize him as a great saint, or at least as someone special?

DG: There were a few. Seshadri Swami, who was also a local saint, spotted him while he was sitting in the Patala Lingam. He tried to look after him and protect him, but without much success. Bhagavan has spoken of one or two other people who intuitively knew that he was in a very elevated state, but in those days, they were very few in numbers.

jd: Were they people in the temple?

DG: Seshadri Swami lived all over the place. There were probably two or three other people who even then recognized him as being something special. Some people revered him simply because he was living such an ascetic life, but there were other people who seemed to know that he was in a high state. The grandfather of a man who later became the ashram’s lawyer was one whom Bhagavan said had a full appreciation of who he really was.

jd: In those days you could easily take his behavior as a sign of being a bit crazy, yes? For example, there was a man in the ashram this morning wearing a loincloth, rather like Bhagavan’s loincloth, with a French accent. He could be a famous saint or he could be a loony. It wouldn’t be very easy to decide at the moment.

DG: People get the benefit of the doubt here, especially if they are sitting all day, absolutely still, and not eating. That’s hard to fake. You don’t sit in full lotus, absolutely motionless, for a few days just to get a free meal. But at the same time, it doesn’t prove you are enlightened. There was a man here in Bhagavan’s time who sat eighteen hours a day in full lotus with his eyes closed. His name was Govind Bhat and he lived in Palakottu, a sadhu colony adjacent to Ramanashram. He tried to attract devotees even while Bhagavan was alive, but he didn’t do very well. In the end it is the enlightenment not the physical antics that attracts the real devotees.

jd: So how did it happen that he moved from there up on the hill?

DG: Have you been to a place called Gurumurtham? It’s a temple about a mile out of town. A man who was looking after Bhagavan invited him to go and stay in a mango orchard that was next to this temple. He moved out there for about a year and a half. That was the furthest away from the mountain he ever went in all his fifty-four years here. Even there he was mostly unaware of his body and the world. He said his fingernails grew to be several inches long. He didn’t comb or wash his hair for a couple of years. Many years later he commented that if one doesn’t comb one’s hair it becomes very matted and it grows very quickly. By the end of his time at Gurumurtham, he had long matted hair and long fingernails.

Gurumurtham

He has said that he could hear people whispering outside, saying ‘This man’s been in there for hundreds of years’. Because of the extent of his asceticism, he looked old even when he was eighteen.

jd: From the way you’re telling the story, it has always been clear that he was a saint.

DG: Clear to whom? It is easy to say this in hindsight, but at the time there were many local people who had no opinion of him at all. The population of Tiruvannamalai around 1900 was probably in the region of 20,000. If twenty people came to see him regularly, and the rest didn’t bother, that means 99.9% of the local people either didn’t know anything about him, or didn’t care enough to pay him a visit.

His uncle, who came in the 1890s to try and bring him home, asked people in town, ‘What’s he doing? Why is he behaving like this?’ The replies he received were not positive. His uncle was led to believe that he was just a truant who should be taken home. Even in later years there were many people in Tiruvannamalai who didn’t have a high opinion of him. The people who became his devotees are the ones who left some records, so the published opinions of him are a bit one-sided.

jd: So, when he was already twenty or so, were there devotees already coming to spend time with him?

DG: He arrived when he was sixteen and for the next two or three years he sometimes had one full-time attendant, plus a few people who occasionally came to see him.

It wasn’t really until the early years of the last century that people started coming regularly. By the beginning of the first decade of the twentieth century he had a small group of followers. A few people brought him food regularly and a few others were frequent visitors. A large number of curiosity seekers would come to have a look at him and go away. Apart from these tourists, he seems to have had perhaps four or five regular devotees.

jd: Were those people local people?

DG: They were mostly locals. One woman called Akhilandamma, who lived about forty miles away, used to come from her village and bring him food once in a while. Another, Sivaprakasam Pillai, lived in another town, but he came fordarshan regularly. Just about everyone else lived here in Tiruvannamalai.

jd: And he went from the mango orchard up onto the hill?

DG: Around 1901 he moved up to Virupaksha Cave and stayed there for about fifteen years, but it was not a good place to live all year round. In summer it was too hot. He stayed there for about eight months a year and then moved to other nearby caves and shrines such as Guhai Namasivaya Temple, Sadguru Swami Cave and a place called Mango Tree Cave.

The entrance to Virupaksha Cave. The photo was taken before extensive modern renovations added a new room to the front.

They are all less than five minutes’ walk from Virupaksha Cave. There’s a big tank up there, Mulaipal Tirtham, a little lower down the hill from Virupaksha Cave. This was the sadhus‘ water supply. Everybody up there was dependent on that tank, so all their caves and their huts were in walking distance of that tank.

jd: Now, it’s become a bit of a farm up there, a lot of cows and what have you.

DG: Things move on.

jd: But in fact there’s a stream that runs right past the cave. Whenever I’ve been there…

DG: It doesn’t run all year, and when Bhagavan moved into the cave it wasn’t there at all. There was a big thunderstorm one summer that produced an avalanche that carried away many of the rocks that were near the cave. After the debris had been cleared away, it was discovered that a new spring was coming out of nearby rocks. The devotees said that it was a gift from Arunachala, and Bhagavan seemed to agree with them.

jd: It seems a nice little water supply.

DG: It’s very seasonal. We have just had a week and a half of good rain. If it doesn’t rain, within a week it will dry up, so it’s not that good a source.

jd: Is that the same spring that goes through Skandashram?

DG: No, Virupaksha Cave has an independent spring. Skandashram probably has the best spring on that side of the hill. That spring also didn’t exist when Bhagavan first moved onto the hill. He went on a walk there – it’s a few hundred feet higher up the mountain from Virupaksha Cave – noticed a damp patch and recommended that it be dug out to see if there was a good water source there. There was, and the stream that now flows through Skandashram is the highest source of permanent water on the hill. It’s about 600 feet above the town.

jd: Does that mean Skandashram didn’t exist in those days?

DG: No. It’s named after a man called Kandaswami who started building it in the early years of the last century.

Kandaswami did a massive amount of work on the site. When he started it was a 45-degree scree slope. He dug back into the side of the hill and used the excavated soil and rocks to make a flat terrace on the side of the hill. He planted many coconut and mango trees, which are still there. It’s a beautiful place now, a shady oasis on the side of the hill.

jd: So when Bhagavan moved up there, it was pretty well set. There were some buildings and a terrace?

DG: The terrace was there and the young trees had been planted, but there was only one small hut that was not big enough for everyone. The devotees of the time did some fundraising and erected the structure that can be seen there today.

jd: Do you know how many people were there with Bhagavan? Half a dozen?

DG: In Virupaksha Cave about four or five would be a good average. By the time Bhagavan moved to Skandashram, the average numbers were probably up to ten or twelve. I am talking about people who lived with Bhagavan full time, and who slept with him at night. There were many other people who just visited and left.

jd: So even in the cave there were in fact people living there with him?

DG: Yes, they ate with him and slept there at night. Many of them left during the day to do things elsewhere. They were not sitting there all the time. They were all men, by the way. Until Bhagavan’s mother arrived in 1914, only men were allowed to sleep in Virupaksha Cave. Even though there was no formal structure, the people who lived with Bhagavan tended to regard themselves as celibate sadhus. They regarded the cave as a men-only ashram.

Initially these sadhus didn’t want Bhagavan’s mother to move in with them. However, when Bhagavan declared, ‘If you make her leave, I will also leave along with her,’ they had to back down and allow her to stay.

jd: So, when he lived in the cave he wasn’t in ‘retreat’ or in ‘solitary silence’. You know, the image of Bhagavan is always of this totally silent, totally alone person.

DG: He behaved differently in different phases of his life. In the late 1890s, when he was in his late teens, he almost never interacted with anyone. Most of the time he just sat with his eyes closed, either in the temple or in nearby temples and shrines. He knew what was going on because in later years he would often talk about incidents from this era, but he hardly ever spoke. The period of rarely speaking lasted for about ten years, up to about 1906. He hadn’t taken a vow of silence, he had just temporarily lost the ability to articulate sounds. When he tried to speak, a kind of guttural noise would initially come out of his throat. Sometimes he would have to make three or four attempts to get the words out. Because it was so hard to speak, he preferred silence.

Around 1906-7, when he recovered his ability to speak normally, he began to interact verbally with the people around him. By this time he was also spending a lot of time wandering around by himself on Arunachala. He loved being out on the mountain. It was his main passion, his only attachment.

jd: And that would be alone? He would go around alone?

DG: Occasionally he would take people out for brief walks but mostly he was alone.

jd: Is it on record who was his first disciple? Perhaps we shouldn’t say ‘first disciple’.

DG: There were people who looked after him in his early years here who could be regarded as his earliest devotees. The most prominent was Palaniswami who looked after him from the 1890s until he passed away in 1915. The two of them were inseparable for almost twenty years.

jd: So this man would have lived at the cave with Bhagavan?

DG: Yes, he was the full-time attendant at Virupaksha Cave. He also lived with Bhagavan at Gurumurtham.

jd: And gradually other people were attracted and would become fairly permanent. Presumably, there was no formal initiation?

DG: I really don’t know who decided, ‘OK, you can sleep here tonight’. There was no management, no check-in department.

Everyone was welcome to come and sit with Bhagavan – all day if they wanted to. And if they were still there at night, they could also sleep there. If food was available, everyone who was present would share.

Bhagavan never had much to do with who was there and who wasn’t, who was allowed to stay and who wasn’t. If people wanted to stay they stayed, and if they wanted to leave they left.

jd: And presumably that continued. I mean, he was never actively involved in managing the ashram, was he?

DG: In the Virupaksha period there wasn’t a lot of work going on. It was a community of begging sadhus who just stayed with Bhagavan whenever they felt like it. People would go to town, beg on the streets, collect the food, and bring it back to Virupaksha Cave. Bhagavan would mix it all up together, distribute it, and that was the food for the day. If not enough food was begged, people went hungry. Nobody was cooking, so there was no work to do except for occasional cleaning. After his mother came in 1914, the kitchen work started. Slowly, slowly it got to the situation where if you wanted to live full time with him, you had to work.

Even today the people who eat and sleep full time in the ashram have to work there. It’s not a place for people who want to sit and meditate all day. If you want to do that, you live somewhere else.

jd: So that would have been when they moved to Skandashram?

DG: It got a bit more organized when Bhagavan moved to Skandashram, but it was still a community of begging sadhus right up to the early 1920s. Bhagavan himself went begging in the 1890s. I wouldn’t say he encouraged begging, but he thought it was a good tradition. Go out and beg your food, eat what people give you, sleep under a tree and wake up the next day with nothing. He heartily approved of a lifestyle like this, but it wasn’t one he could follow himself once he settled down and an ashram grew up around him.

jd: And he wore just a loincloth?

DG: In the beginning, for the first few months, he was naked. A couple of months after he arrived, there was a big festival in the temple. Some devotees lifted him up and dressed him in a loincloth because they knew that he might be arrested if he sat in a prominent place with no clothes on. For most of his life he only wore a loincloth, occasionally supplemented by a dhoti that he would tie under his armpits, rather than round his waist. It gets quite cold here on winter mornings, but he never seemed to want or need more clothes.

jd: When did the ashram begin to get big?

DG: Coming down the hill was the big move in Bhagavan’s life. When his mother died in 1922, she was buried where the ashram is now located. The spot was chosen because it was the Hindu graveyard in those days. Bhagavan continued to live at Skandashram, but about six months later he came down the hill and didn’t go back up. He never gave any reason for staying at the foot of the hill. He just said he didn’t feel any impulse to go back to Skandashram. That’s how the current Ramanashram started.

jd: So the ashram’s actually built on a Hindu burial ground?

DG: Yes. In those days the graveyard was well outside the town. Now the town has expanded to include Ramanashram, and the present Hindu graveyard is now a mile further out of town.

jd: How did the ashram come to take over the land round here?

DG: The place where Bhagavan’s mother was buried was actually owned by amath, a religious institution, in town. The man who headed that organization had a high opinion of Bhagavan, so he handed over the land to the emerging Ramanashram. When Bhagavan’s mother died, the devotees had to get permission from the head of this math to bury her on this land, but there was no problem since he was also a devotee.

jd: And the first building, was it the shrine over the mother’s grave?

DG: Well, shrine is a bit of a fancy word. A really wonderful photo was taken here in 1922, shortly after Bhagavan settled here. The only building is a coconut-leaf hut. It looks as if one good gust of wind would blow it over. People who came to see him that year have reported that there wasn’t even room for two people in the room where Bhagavan lived. That was the first ashram building here: a coconut-leaf hut that probably leaked when it rained.

The beginnings of Sri Ramanasramam in 1922

jd: It’s very beautiful now – water, trees, peacocks. It must have been very primitive eighty years ago.

DG: I talked to the man who cleared the land here. He told me there were large boulders and many cacti and thorn bushes. It wasn’t really forest. It’s not the right climate for a luxuriant forest, and there isn’t much soil. The granite bedrock is often close to the surface, and there are many rocky outcrops. This man, Ramaswami Pillai, said that he spent the first six months prising out boulders with a crowbar, cutting down cacti and leveling the ground.

jd: When the building started, was Bhagavan himself involved in that?

DG: I don’t think be built the first coconut leaf hut but once he moved here he was very much a hands-on manager. The first proper building over the Mother’s Samadhi was organized and built by him. Have you seen how bricks are made round here?

jd: Possibly.

DG: It’s like making mud pies. You start with a brick-shaped mould. You make a pile of mud and then use the mould to make thousands of mud bricks that you put out in the sun to dry. After they have been properly dried, you stack them in a structure the size of a house that has big holes in the base for logs to be put in. The outside of the stack is sealed with wet mud and fires are lit at the base. Once the fire has taken, the bottom is sealed as well. The bricks are baked in a hot, oxygen-free environment, in the same way that charcoal is made. After two or three days the fires die down, and if nothing has gone wrong, the bricks are properly baked. However, if the fires go out too soon, or if it rains heavily during the baking, the bricks don’t get cooked properly. When that happens, the whole production is often wasted because the bricks are soft and crumbly – more like biscuits rather than bricks.

In the 1920s someone tried to make bricks near the ashram, but the baking was unsuccessful and all the half-baked bricks were abandoned. Bhagavan, who abhorred waste of any kind, decided to use all these commercially useless bricks to build a shrine over his mother’s grave. One night he had everyone in the ashram line up between the kiln and the ashram. Bricks were passed from hand to hand until there were enough in the ashram to make a building. The next day he did the bricklaying himself as he and his devotees raised a wall around the samadhi. Bhagavan did a lot of work on the inside of the wall because people felt that, since it was going to be a temple, the interior work should be done by brahmins.

This was the only building that he constructed himself, but years later, when the large granite buildings that make up much of the present ashram were erected, he was the architect, the engineer and the building supervisor. He was there every day, giving orders and checking up on progress.

jd: You say he ‘abhorred waste’. Can you expand on that a little?

DG: He had the attitude that anything that came to the ashram was a gift from God, and that it should be properly utilized. He would pick up stray mustard seeds that he found on the kitchen floor with his fingernails and insist that they be stored and used; he used to cut the white margins off proof copies of ashram books, stitch them together and make little notebooks out of them; he would attempt to cook parts of vegetables, such as the spiky ends of aubergines, that are normally thrown away. He admitted that he was a bit of a fanatic on this subject.

He once remarked, ‘It’s a good thing I never got married. No woman would have able to put up with my habits.’

jd: Going back to his building activities, how involved in day-to-day decisions was he? Did he, for example, decide where the doors and windows went?

DG: Yes. Either he would explain what he wanted verbally, or he would make little sketches on the backs of envelopes or on scrap pieces of paper.

jd: What you’re describing now is a totally different Bhagavan from the one who sat in samadhi all day. Most people think that he spent his whole life sitting quietly in the hall, doing nothing.

DG: He didn’t like sitting in the hall all day. He often said that it was his prison. If he was off doing some work when visitors came, someone would come and tell him that he was needed in the hall. That’s where he usually met with new people.

He would sigh and remark, ‘People have come. I have to go back to jail.’

jd: ‘Got to go sit on the couch’.

DG: Yes. ‘Got to go and sit on the couch and tell people how to get enlightened.’

Bhagavan enjoyed all kinds of physical work, but he particularly enjoyed cooking. He was the ashram’s head cook for at least fifteen years. He got up at two or three o’clock every morning, cut vegetables and supervised the cooking. When the new ashram buildings were going up in the 1920s and 30s, he was also the supervising engineer and architect.

jd: I think what you’ve just been speaking about is in a way very important in general. People have set ideas about Bhagavan. Most people have an image of him as a man who sat on a couch, looking blissful and doing nothing. What you are describing is a completely different man.

DG: His state didn’t change from the age of sixteen onwards, but his outer activities did. In the beginning of his life here at Arunachala he was quiet and rarely did anything. Thirty years later he had a hectic and busy schedule, but his experience of who he was never wavered during this later phase of busy-ness.

jd: I like the way you’re speaking because in a way you’re debunking a lot of spiritual myths.

DG: Bhagavan never felt comfortable with a situation in which he sat on a couch in the role of a ‘Guru’, with everyone on the floor around him. He liked to work and live with people, interacting with them in a normal, natural way, but as the years went by, the possibilities for this kind of life became less and less.

One of the problems was that people were often completely overawed by him. Most people couldn’t act normally around him. Many of the visitors wanted to put him on a pedestal and treat him like a god, but he didn’t seem to appreciate that kind of treatment.

There are some nice stories of new people behaving naturally and getting a natural response from Bhagavan. Major Chadwick wrote that Bhagavan would come to his room after lunch, go through his things like an inquisitive child, sit on the bed and chat with him. However, when Chadwick once put out a chair in the expectation of Bhagavan’s arrival, the visits stopped. Chadwick had made the transition from having a ‘friend’ who dropped by to having a Guru who needed respect and a special chair. When this formality was introduced, the visits ended.

jd: So he saw himself as a ‘friend’ not as ‘the Master’.

DG: Bhagavan didn’t have a perspective of his own, he simply reacted to the way people around him thought about him and treated him. He could be a friend, a father, a brother, a god, depending on the devotee’s way of approaching him. One woman was convinced that Bhagavan was her baby son. She had a little doll that looked like Bhagavan, and she would cradle it like a baby when she was in his presence. Her belief in this relationship was so strong, she actually started lactating when she held her Bhagavan doll.

Bhagavan seemed to approve of any Guru-disciple relationship that kept the devotee’s attention on the Self or the form of the Guru, but at the same time he still liked and enjoyed people who could treat him as a normal being.

Bhagavan sometimes said that it didn’t matter how you regarded the Guru, so long as you could think about him all the time. As an extreme example he cited two people from ancient times who got enlightened by hating God so much, they couldn’t stop thinking about Him.

There is a Tamil phrase that translates as ‘Mother-father-Guru-God’. A lot of people felt that way about him.

Bhagavan himself said he never felt that he was a Guru in a Guru-disciple relationship with anyone. His public position was that he didn’t have any disciples at all because, he said, from the perspective of the Self there was no one who was different or separate from him. Being the Self and knowing that the Self alone exists, he knew that there were no unenlightened people who needed to be enlightened. He said he only ever saw enlightened people around him.

Having said that, Bhagavan clearly did function as a Guru to the thousands of people who had faith in him and who tried to carry out his teachings.

jd: During which period was Bhagavan actively involved in the building work?

DG: The ashram started to change from coconut-leaf structures to stone buildings around 1930. The big building phase was 1930-42. The Mother’s Temple was built after that, but Bhagavan wasn’t supervising the design and construction of that so much. That work was subcontracted to expert temple builders. Bhagavan visited the site regularly, but he wasn’t so involved in design or engineering decisions.

jd: If anybody had visited during those twelve years they would have found a Bhagavan who was not sitting on the couch. They would have found him out working, supervising workers?

DG: It would have depended on when they came. Bhagavan had a routine that he kept to. He was always in the hall for the morning and evening chanting – two periods of about forty-five minutes each. He would be there in the evening, chatting to all the ashram’s workers who could not see him during the day because of their various duties in different parts of the ashram. He would be there if visitors arrived who wanted to speak to him. He walked regularly on the hill, or to Palakottu, an area adjacent to the ashram. These walks generally took place after meals. He would fit in his other jobs around these events. If nothing or no one needed his attention in the hall, he might go and see how the cooks were getting on, or he might go to the cowshed to check up on the ashram’s cows. If there was a big building project going on, he would often go out to check up on the progress of the work. Mostly though, he did his tours of the building sites after lunch, when everyone else was having a siesta.

He supervised many workers, not just the ones who put up the buildings. Devotees in the hall would bind and rebind books under his supervision, the cooks would work according to his instructions, and so on. The only area he didn’t seem inclined to get involved in was the ashram office. He let his brother have a fairly free rein there, although once in a while he would intervene if he felt that something that had been neglected ought to be done.

In earlier years, up to 1926, he would also walk round the base of Arunachala quite regularly.

jd: Would a few people follow him?

DG: Yes, large crowds would go with him in the later years, and when he passed through town there would be even more people waiting for him, trying to feed him, or attempting to get him into their houses. He turned down all these invitations. After the 1890s he never entered a private house in town.

He stopped going round the hill in 1926 because people started fighting over who should stay behind in the ashram. No one wanted to be left behind, but someone always had to remain to guard the property.

Finally he said, ‘If I stop going there won’t be any more fights about who is going to stay behind’.

He never did the walk again.

jd: You were saying he was a very natural person who liked very natural people. I presume he also liked animals.

DG: Almost all of them. I have read that he didn’t particularly like cats, but I don’t know what the evidence is for that. As far as I can make out, he loved all the animals in the ashram. He showed a particular fondness for the dogs, the monkeys and the squirrels.

jd: And they, presumably, lived in the ashram as well?

DG: Bhagavan used to say that people in the ashram were squatting on land that belonged to the animals, and that the local wild animals had prior tenancy rights. He never approved of animals being driven away either to make more room for people, or because some people didn’t like having animals around. He always took the side of the animals whenever there was any attempt to throw them out or inconvenience them in any way.

He had squirrels on his sofa. They moved in and made nests in the grass roof over his head, they ran all over his body, and had babies in his cushions. Once in a while he’d sit on one and accidentally suffocate it. They were all over the place.

jd: He sounds like a very natural person who felt it normal and natural to have animals around him.

DG: It was natural and normal for him, but it was not natural and normal for many the people who congregated around him. Bhagavan always had to fight in the animals’ corner to make sure they got proper treatment, or were not unnecessarily inconvenienced.

The big new hall, the stone building in front of the Mother’s Temple, was built for Bhagavan in the 1940s. The old hall that he had lived in since the late 1920s was by then too small for the crowds of people that wanted to see him. The new hall was a large, grandiose, granite space that resembled a temple mantapam, but it was an intimidating place for some people and for all of the animals.

When Bhagavan was shown where he was going to sit, he asked, ‘What about the squirrels? Where are they going to live?’

There were no niches for them to sit in, or grassy materials to raid for their nests. Bhagavan also complained that the building would intimidate some of the poor people who wanted to come and see him. He always saw things like this from the side of the underdog, whether animal or human.

jd: That large stone couch somehow seems to be for the wrong person.

DG: Yes, that wasn’t his style at all. There was a sculptor making a stone statue of him at the same time that the finishing touches were being made to this new hall. When Bhagavan was told that this new carved, granite sofa was for him, he remarked, ‘Let the stone swami sit on the stone sofa’. He eventually did move into this hall because there was nowhere else where he could meet with large numbers of people, but he didn’t stay there long.

jd: And that was about a year before he gave up his body?

DG: The temple over his Mother’s samadhi was inaugurated in March 1949, and Bhagavan moved into the new hall shortly afterwards. He developed a cancer, a sarcoma, on his arm that year. It physically debilitated him to the extent that he couldn’t walk to his bathroom and back. At that point his bathroom was converted into a room for him. That’s where he spent the last few months of his life.

jd: That’s the place they call the samadhi room?

DG: Yes. An energetic Tamil woman, Janaki Amma, came to the ashram in the 1940s. When she asked to be shown to the women’s bathroom, she was told that there wasn’t one. She arranged for one to be built, and this was the room that Bhagavan spent his final days in. It was the nearest bathroom to the new hall that he moved into in 1949. It became his bathroom at that time because no one wanted to inconvenience him by making him walk any further. He refused to let anyone help him when he walked to this bathroom, even when he was extremely weak. Have you seen the video of him in his last year?

jd: Probably.

DG: It’s excruciating to watch. His knees have massive swellings on them, and they seem to shake from side to side. It is clear from this footage that he was extremely debilitated, but he would never let anyone help him to move around. There is an elaborate stone step in the doorway of the new hall. Devotees would have to stand by, completely helpless, as Bhagavan would attempt to climb over this obstruction. No one was allowed to offer assistance. Eventually, when this step proved to be too much of an obstacle, he moved into the bathroom and stayed there until he passed away in April 1950.

jd: Is it right that during that time he was still available?

DG: He was very insistent that anyone who wanted to see him could have darshanat least once a day. When people realized he wasn’t going to be here much longer, the crowds increased. For the last few weeks there was a ‘walking darshan‘. People would file past his room and pranam to him one by one.

jd: And that went on until his last day?

DG: Yes, he gave his final public darshan on the afternoon of the day he died.

jd: Yes, I actually met someone who walked past him the day before he died.

DG: He insisted that the public should have as much access as possible. Up until the 1940s, the doors of his room were open twenty-four hours a day. If you wanted to see him at 3 a.m., no one would stop you from walking in and seeing him. If you had some problem, you could go and tell him in the middle of the night.

jd: So even though he was doing a lot of work – cutting vegetables, working on the buildings and so on – he was, in fact, always available?

DG: In that era of his life there weren’t too many people around him. You are talking about the years when he was actively involved in cooking and building work. In those days, if a group of people came to see him, he would go to the hall to see what they wanted.

Everybody who lived in the ashram had a job. You were either working in the cowshed or the kitchen, the garden, the office, and so on. These ashram residents were not allowed to sit with Bhagavan during the day because they had work to do. In the evening all the ashram workers would gather around Bhagavan, and for a few hours they would generally have him to themselves. The visitors would usually go home in the evening. The people whom he saw during the day in the hall would be visitors to the ashram, along with a few devotees who had houses nearby.

jd: Was everyone free to question him?

DG: In theory, yes, but many people were far too intimidated to approach him. He would sometimes talk without prompting, without being questioned. He liked to tell stories about famous saints, and he often told stories about what had happened to him in various stages of his life. He was a great storyteller, and whenever he had a good story to tell, he would act out the parts of the various protagonists. He would get so involved in the narratives, he would often start crying when he came to a particularly moving part of the story.

jd: So the impression of him being silent is not really true?

DG: He was silent for much of the day. He told people that he preferred to remain in silence, but he did speak, often for hours at a time, when he was in the mood.

I’m not saying that everyone who came to see him got a prompt verbal answer to his or her question. You could come and ask an apparently earnest question, and Bhagavan might ignore you. He might stare out of the window and show no sign that he had even heard what you had said. Someone else might come in and ask a question and get an immediate reply. It sometimes looked like a bit of a lottery, but everyone in the end got what they needed or deserved. Bhagavan responded to what was going on in the minds of the people who were in front of him, not just to their questions, and since he was the only person who could see what was going on in that sphere, his responses at times seemed to outsiders to be occasionally random or arbitrary.

Many people would ask something and not get a spoken answer, but they would find later that merely sitting in his presence had given them the peace or the answer they required. This was the kind of response that Bhagavan preferred to make: a silent, healing stream of grace that gave people peace, not just a satisfactory spoken answer.

jd: When did he begin to give out teachings, and what were they? I have been told that when he was living in a cave on the hill someone came to him and asked what his teachings were. He apparently wrote them out in a small booklet. Can you say something about this?

DG: This was 1901. He didn’t even have a notebook. A man called Sivaprakasam Pillai came and asked questions. His basic question was ‘Who am I? How do I find out who I really am?’ The dialogue developed from there, but no words were spoken. Bhagavan wrote his answers with his finger in the sand because this was the period in which he found it difficult to articulate sounds. This primitive writing medium produced short, pithy answers.

Sivaprakasam Pillai didn’t write down these answers. After each new question was asked, Bhagavan would wipe out his previous reply and pen a new one with his finger. When he went home, Sivaprakasam Pillai wrote down what he could remember of this silent conversation.

About twenty years later he published these questions and answers as an appendix to a brief biography of Bhagavan that he had written and published. I think there were thirteen questions and answers in this first published version. Bhagavan’s devotees appreciated this particular presentation. Ramanashram published it as a separate booklet, and with each edition more and more questions and answers were added. The longest version has about thirty.

At some point in the 1920s Bhagavan himself rewrote this series of questions and answers as a prose essay, elaborating on some answers and deleting others. This is now published under the title Who Am I? in Bhagavan’s Collected Works, and separately as a small pamphlet. It is simply Bhagavan’s summary of answers written with his finger more than twenty years before.

jd: It sounds fairly brief.

DG: Yes, it is probably about six pages in most books.

jd: The key is this question ‘Who am I?’ Is that right?

DG: It’s called Who am I? but it covers all kinds of things: the nature of happiness, what the world is, how it apparently comes into existence, how it disappears. There is also a detailed portion that explains how to do self-enquiry.

jd: You could say something on that. I’ve personally been reading about self-enquiry for many years but it’s never quite clear exactly what it is. Is it something you do in the morning as a practice? Is it something you do once or regularly? Is it like a breathing technique or a type of meditation?

DG: Papaji always used to say ‘Do it once and do it properly’. That’s the ideal way, but I only know of two or three people who have done it once and got the right answer: a direct experience of the Self. These people were ready for a direct experience, so when they asked the question, the Self responded with the right answer, the right experience.

jd: Like Papaji himself?

DG: Papaji never did self-enquiry, although he did advocate it vigorously once he started teaching.

I’m thinking of two remarkable people who both came to Bhagavan in the late 1940s. One was a woman who had had many visions of Murugan, her chosen deity. She was a devotee who had never heard of self-enquiry. She didn’t even know much about Bhagavan when she stood in front of him in April 1950. She was one of the people who had ‘walking darshan‘ in Bhagavan’s final days. As she stood in front of Bhagavan, the question ‘Who am I?’ spontaneously appeared inside her, and as an answer she immediately had a direct experience of the Self. She said later that this was the first time in her life that she had experienced Brahman.

The second person I am thinking of is Lakshmana Swamy. He, too, had not done any self-enquiry before. He had been a devotee for only a few months and during that time he had been repeating Bhagavan’s name as a spiritual practice. In October 1949 he sat in Bhagavan’s presence and closed his eyes. The question ‘Who am I?’ spontaneously appeared inside him, and as an answer his mind went back to its source, the Heart, and never appeared again. In his case it was a permanent experience, a true Self-realization.

In both cases there had been no prior practice of self-enquiry, and in both cases the question ‘Who am I?’ appeared spontaneously within them. It wasn’t asked with volition. These people were ready for an experience of the Self. In Bhagavan’s presence the question appeared within them, and in his presence their sense of individuality vanished. In my opinion being in the physical presence was just as important as the asking of the question.

Many other people have asked the question endlessly without getting the result that these people got from having the question appear in them once.

I should also like to point out that both these people had their experiences in the last few months of Bhagavan’s life. Though his body was disintegrating, physically enfeebling him, his spiritual power, his physical presence, remained just as strong as ever.

jd: Are you saying that self-enquiry is not a practice, that it is not something that we should do laboriously, hour after hour, day after day?

DG: It is a practice for the vast majority of people, and Bhagavan did encourage people to do it as often as they could. He said that the practice should be persisted with, right up to the moment of realization.

It wasn’t his only teaching, and he didn’t tell everyone who came to him to do it. Generally, when people approached him and asked for spiritual advice, he would ask them what practice they were doing. They would tell him, and his usual response would be, ‘Very good, carry on with that’.

He didn’t have a strong missionary zeal for self-enquiry, but he did say that sooner or later everyone has to come to self-enquiry because this is the only effective way of eliminating the individual ‘I’. He knew that most people who approached him preferred to repeat the name of God or worship a particular form of him. So, he let them carry on with whatever practice they felt an affinity with.

However, if you came to him and asked, ‘I’m not doing any practice at the moment, but I want to get enlightened. What is the quickest and most direct way to accomplish this?’ he would almost invariably reply, ‘Do self-inquiry’.

jd: Is he on the record as saying that it is the quickest and most direct way?

DG: Yes. He mentioned this on many occasions, but it was not his style to force it on people. He wanted devotees to come to it when they were ready for it.

jd: So even though he accepted whatever practices people were involved in, he was quite clear the quickest and most direct tool would be self-enquiry?

DG: Yes, and he also said that you had to stick with it right up to the moment of realization.

For Bhagavan, it wasn’t a technique that you practiced for an hour a day, sitting cross-legged on the floor. It is something you should do every waking moment, in combination with whatever actions the body is doing.

He said that beginners could start by doing it sitting, with closed eyes, but for everyone else, he expected it to be done during ordinary daily activities.

jd: With regard to the actual technique, would you say that it is to be aware, from moment to moment, what is going on in the mind?

DG: No, it’s nothing to do with being aware of the contents of the mind. It’s a very specific method that aims to find out where the individual sense of ‘I’ arises. Self-enquiry is an active investigation, not a passive witnessing.

For example, you may be thinking about what you had for breakfast, or you may be looking at a tree in the garden. In self-enquiry, you don’t simply maintain an awareness of these thoughts, you put your attention on the thinker who has the thought, the perceiver who has the perception. There is an ‘I’ who thinks, an ‘I’ who perceives, and this ‘I’ is also a thought. Bhagavan’s advice was to focus on this inner sense of ‘I’ in order to find out what it really is. In self-enquiry you are trying to find out where this ‘I’ feeling arises, to go back to that place and stay there. It is not simply watching, it’s a kind of active scrutiny in which one is trying to find out how the sense of being an individual person comes into being.

You can investigate the nature of this ‘I’ by formally asking yourself, ‘Who am I?’ or ‘Where does this ”I” come from?’ Alternatively, you can try to maintain a continuous awareness of this inner feeling of ‘I’. Either approach would count as self-enquiry. You should not suggest answers to the question, such as ‘I am consciousness’ because any answer you give yourself is conceptual rather than experiential. The only correct answer is a direct experience of the Self.

jd: It’s very clear what you just said, but almost impossible to accomplish. It sounds simple, but I know from my own experience that it’s very hard.

DG: It needs practice and commitment. You have to keep at it and not give up. The practice slowly changes the habits of the mind. By doing this practice regularly and continuously, you remove your focus from superficial streams of thoughts and relocate it at the place where thought itself begins to manifest. In that latter place you begin to experience the peace and stillness of the Self, and that gives you the incentive to continue.

Bhagavan had a very appropriate analogy for this process. Imagine that you have a bull, and that you keep it in a stable. If you leave the door open, the bull will wander out, looking for food. It may find food, but a lot of the time it will get into trouble by grazing in cultivated fields. The owners of these fields will beat it with sticks and throw stones at it to chase it away, but it will come back again and again, and suffer repeatedly, because it doesn’t understand the notion of field boundaries. It is just programmed to look for food and to eat it wherever it finds something edible.

The bull is the mind, the stable is the Heart where it arises and to where it returns, and the grazing in the fields represents the mind’s painful addiction to seeking pleasure in outside objects.

Bhagavan said that most mind-control techniques forcibly restrain the bull to stop it moving around, but they don’t do anything about the bull’s fundamental desire to wander and get itself into trouble.

You can tie up the mind temporarily with japa or breath control, but when these restraints are loosened, the mind just wanders off again, gets involved in more mischief and suffers again. You can tie up a bull, but it won’t like it. You will just end up with an angry, cantankerous bull that will probably be looking for a chance to commit some act of violence on you.

Bhagavan likened self-enquiry to holding a bunch of fresh grass under the bull’s nose. As the bull approaches it, you move away in the direction of the stable door and the bull follows you. You lead it back into the stable, and it voluntarily follows you because it wants the pleasure of eating the grass that you are holding in front of it. Once it is inside the stable, you allow it to eat the abundant grass that is always stored there. The door of the stable is always left open, and the bull is free to leave and roam about at any time. There is no punishment or restraint. The bull will go out repeatedly, because it is the nature of such animals to wander in search of food. And each time they go out, they will be punished for straying into forbidden areas.

Every time you notice that your bull has wandered out, tempt it back into its stable with the same technique. Don’t try to beat it into submission, or you may be attacked yourself, and don’t try to solve the problem forcibly by locking it up.

Sooner or later even the dimmest of bulls will understand that, since there is a perpetual supply of tasty food in the stable, there is no point wandering around outside, because that always leads to sufferings and punishments. Even though the stable door is always open, the bull will eventually stay inside and enjoy the food that is always there. This is self-enquiry.

Whenever you find the mind wandering around in external objects and senses perceptions, take it back to its stable, which is the Heart, the source from which it rises and to which it returns. In that place it can enjoy the peace and bliss of the Self. When it wanders around outside, looking for pleasure and happiness, it just gets into trouble, but when it stays at home in the Heart, it enjoys peace and silence. Eventually, even though the stable door is always open, the mind will choose to stay at home and not wander about.

Bhagavan said that the way of restraint was the way of the yogi. Yogis try to achieve restraint by forcing the mind to be still. Self-enquiry gives the mind the option of wandering wherever it wants to, and it achieves its success by gently persuading the mind that it will always be happier staying at home.

jd: In that very moment when you realize there’s plenty of grass at home and therefore no need to go out, would you call that awakening?

DG: No, I would just call it understanding.

jd: That’s only understanding? Surely, once you’ve perceived that there are piles of grass at home, why would you want to go out again?

DG: The notion of being better off at home belongs to the ‘I’, and that ‘I’ has to go before realization can happen.

Let’s pursue this analogy a little more. What I will say now is not part of Bhagavan’s original analogy, but it does incorporate other parts of his teaching.

For realization, for a true and permanent awakening, the bull has to die. While it is alive, and while the door is still open, there is always the possibility that it will stray. If it dies, though, it can never be tempted outside again. In realization, the mind is dead. It is not a state in which the mind is simply experiencing the peace of the Self.

When the mind goes voluntarily into the Heart and stays there, feeling no urge whatsoever to jump out again, the Self destroys it, and Self alone remains.

This is a key part of Bhagavan’s teachings: the Self can only destroy the mind when the mind no longer has any tendency to move outwards. While those outward-moving tendencies are still present, even in a latent form, the mind will always be too strong for the Self to dissolve it completely.

This is why Bhagavan’s way works and the forcible-restraint way doesn’t. You can keep the mind restrained for decades, but such a mind will never be consumed by the Self because the desires, the tendencies, the vasanas, are still there. They may not be manifesting, but they are still there.

Ultimately, it is the grace or power of the Self that eliminates the final vestiges of the desire-free mind. The mind cannot eliminate itself, but it can offer itself up as a sacrifice to the Self. Through effort, through enquiry, one can take the mind back to the Self and keep it there in a desire-free state. However, mind can’t do anything more than that. In that final moment it is the power of the Self within that pulls the last remains of the mind back into itself and eliminates it completely.

jd: You say that in realization the mind is dead. People who are enlightened seem to think, remember, and so on, in the just the same way that ordinary people do. They must have a mind to do this. Perhaps they are not attached to it, but it must still be there otherwise they couldn’t function in the world. Someone who had a dead mind would be a zombie.

DG: This is a misconception that many people have because they can’t imagine how anyone can function, take decisions, speak, and so on without a mind. You do all these things with your mind, or at least you think you do, so when you see a sage behaving normally in the world, you automatically assume that he too is coordinating all his activities through an entity called ‘mind’.

You think you are a person inhabiting a body, so when you look at a sage you automatically assume that he too is a person functioning through a body. The sage doesn’t see himself that way at all. He knows that the Self alone exists, that a body appears in that Self and performs certain actions. He knows that all the actions and words that arise in this body come from the Self alone. He doesn’t make the mistake of attributing them to an imaginary intermediary entity called ‘mind’. In this mindless state, no one is organizing mental information, no one is deciding what to do next. The Self merely prompts the body to do or say whatever needs to be done or said in that moment.

When the mind has gone, leaving only the Self, the one who decides future courses of actions has gone, the performer of actions has gone, the thinker of thoughts has gone, the perceiver of perceptions has gone. Self alone remains, and that Self takes care of all the things that the body needs to say or do. Someone who is in that state always does the most appropriate thing, always says the most appropriate thing, because all the words and all the actions come directly from the Self.

Bhagavan once compared himself to a radio. A voice is coming out of it, saying sensible things that seem to be a product of rational, considered thought, but if you open the radio, there is no one in there thinking and deciding.

When you listen to a sage such as Bhagavan, you are not listening to words that come from a mind, you are listening to words that come directly from the Self. In his written works Bhagavan uses the term manonasa to describe the state of liberation. It means, quite unequivocally, ‘destroyed mind’.

The mind, according to Bhagavan, is just a wrong idea, a mistaken belief. It comes into existence when the ‘I’-thought, the sense of individuality, claims ownership of all the thoughts and perceptions that the brain processes. When this happens, you end up with a mind that says, ‘I am happy’ or ‘I have a problem’ or ‘I see that tree over there’.

When, through self-enquiry, the mind is dissolved in its source there is an understanding that the mind never really existed, that it was just an erroneous idea that was believed in simply because its true nature and origin were never properly investigated. Bhagavan sometimes compared the mind to a gatecrasher at a wedding who causes trouble and gets away with it because the bride’s party thinks he is with the bridegroom and vice versa. The mind doesn’t belong to either the Self or the body. It’s just an interloper that causes trouble because we never take the trouble to find out where it has come from. When we make that investigation, mind, like the troublesome wedding guest, just melts away and disappears.

Let me give you a beautiful description of how Bhagavan spoke. It comes from part three of The Power of the Presence. It was written by G. V. Subbaramayya, a devotee who had intimate contact with Bhagavan. It illustrates very well my thesis that the words of a sage come from the Self, not from a mind:

Sri Bhagavan’s manner of speaking was itself unique. His normal state was silence. He spoke so little, casual visitors who only saw him for a short while wondered whether he ever spoke. To put questions to him and to elicit his replies was an art in itself that required an unusual exercise in self-control. A sincere doubt, an earnest question submitted to him never went without an answer, though sometimes his silence itself was the best answer to particular questions. A questioner needed to be able to wait patiently. To have the maximum chance of receiving a good answer, you had to put your question simply and briefly. Then you had to remain quiet and attentive. Sri Bhagavan would take his time and then begin slowly and haltingly to speak. As his speech continued, it would gather momentum. It would be like a drizzle gradually strengthening into a shower. Sometimes it might go on for hours together, holding the audience spellbound. But throughout the talk you had to keep completely still and not butt in with counter remarks. Any interruption from you would break the thread of his discourse and he would at once resume silence. He would never enter into a discussion, nor would he argue with anyone. The fact was, what he spoke was not a view or an opinion but the direct emanation of light from within that manifested as words in order to dispel the darkness of ignorance. The whole purpose of his reply was to make you turn inward, to make you see the light of truth within yourself.

jd: Can we go back to the analogy of the bull that has to be enticed back into its stable? It seems the bull, which represents the mind, has to die. When the mind dies, can this considered to be a full awakening? Is there a difference between awakening and enlightenment? Obviously, we’re just using words, but are there two different states?

DG: Self is always the same. Self being aware of the Self is always the same. Different levels of experiences belong to the mind, not the Self.

Mind can be temporarily suspended, having been replaced by what appears to be a direct experience of the Self. Nevertheless, this is not the sahaja state, the permanent natural state in which the mind can never rise again. These temporary states are very subtle experiences of the mind. The bliss and peace of the Self are being experienced, being mediated through an ‘I’ that has not yet been fully eliminated.

For example, I experience being in this room. I mediate it through my senses, through my knowledge, my memory. When the ‘I’ goes back into the Heart and remains still without rising, there, in that state, it experiences the emanations of the Self; the quietness, the peace, the bliss.

This is still an experience, and as such, it is not enlightenment. It’s not the full awareness of the Self. That full awareness is only there when there is no ‘I’ that mediates it. The experiences of the Self that happen when the ‘I’ is still existing may be regarded as a ‘preview of forthcoming attractions’, like the trailers for next week’s movie, but they are not the final, irreversible state. They come and they go, and when they go, mind returns with all its usual, annoying vigour.

jd: How does one progress from these temporary experiences to a permanent one? Is keeping still enough, or is grace required?

DG: I would like to bring in Lakshmana Swamy again at this point. I mentioned him earlier as being an example of someone who realized the Self in Bhagavan’s presence through the practice of self-enquiry. So, we are dealing with an expert here; someone who knows what he is talking about.

Lakshmana Swamy is quite clear on this point. He says that devotees can, by their own effort, reach what he calls ‘the effortless thought-free state’. That’s as far as you can go by yourself. In that state there are no more thoughts, desires or memories rising up. They are not being suppressed; they simply don’t rise up any more to grab your attention.

Lakshmana Swamy says that if you reach that state through your own intense efforts and then go and sit in the presence of a realized being, the power of the Self will make the residual ‘I’ go back to its source where it will die and never rise again. This is the complete and full realization. This is the role of the Guru, who is identical with the Self within: to pull the desire-free mind into the Heart and destroy it completely.

As I mentioned before, this won’t happen if the desires and tendencies of the mind are still latent. They all have to go before this final act of execution can be achieved. The disciple himself has to remove all the unwanted lumber from his mental attic, and he also needs to be in a state in which there is no desire to put anything more into it. The Guru cannot do this work for him; he has to do it himself. When this has been accomplished, the power of the Self within, the inner Guru, will complete the work.

jd: We’ve both had this common experience of living around Papaji, and we have both heard him say to people ‘You’ve got it!’ Was he referring to that first temporary state or the second, final irrevocable state?

DG: I would say almost invariably the first. His particular knack, his talent, his skill was to completely pull the mental chair out from underneath you. He would somehow, instantaneously, disentangle you from the superstructure, the infrastructure of the mind, and you would fall – Plop! – right into the Self. You would then immediately think, ‘This is great! This is wonderful! I’m enlightened!’

He had this astonishing talent, this power of being able to rub your nose in the reality of the Self. It was completely spontaneous because most of the time he wasn’t even aware that he was doing it. Somehow, in his presence people lost this sense of functioning through the individual ‘I’. When this happened you would be completely immersed in the feeling, the knowledge of being the Self. However, it wouldn’t stick for the reasons I have already given. If you haven’t cleared out all the lumber from your mental attic, these experiences will be temporary. Sooner or later the mind will reassert itself and this apparent experience of the Self will fade away. It might last ten days, ten weeks, ten months or even years, but then it goes away and just leaves a memory.

jd: Does that mean that this second final state is very, very, very rare?

DG: In the Bhagavad Gita Krishna says, ‘Out of every thousand people one is really serious, and out of every thousand serious people only one knows me as I really am’.

That’s one in a million, and I think that’s a very generous estimate. Personally, I think it’s far fewer than that.

jd: This bring us to the subject of your recent series of books. In these books you have chosen people who were close to Bhagavan. Presumably, you chose people who you feel have reached that final state.

DG: No, that wasn’t the criterion at all. Initially, my aim was to bring into the public domain accounts by devotees of Bhagavan that hadn’t been published before in English. I make no judgments about spiritual maturity or accomplishments. My prime consideration was ‘Has this been published before in English, and if it hasn’t, is it interesting enough to print now?’

jd: So you don’t in any way suggest in the book that they’ve reached this or that state?

DG: I let people speak for themselves.

The second chapter of part one of The Power of the Presence, for example, is about a man, Sivaprakasam Pillai, who spent fifty years with Bhagavan. I have already mentioned him; he was the person who recorded the answers that Bhagavan wrote in the sand in 1901. In many parts of this chapter he’s lamenting ‘I’ve wasted my life’, ‘I’m worse than a dog’, ‘I’ve sat here for many years without making any progress’.

jd: But this man might have got it in that period, even if he thinks he didn’t.

DG: In Bhagavan’s day there was a daily chanting of Tamil devotional poetry. There was a fixed selection of material that took fifteen days to go through. Sivapraksam Pillai’s poems were part of this cycle. Every fifteen days the devotees would sit in front of Bhagavan and chant ‘I am worse than a dog,’ and so on.

Somebody asked Bhagavan, ‘This man has been here fifty years and he is still in this state. What hope is there for us?’

Bhagavan replied, ‘That’s his way of praising me’.

When Sivaprakasam Pillai died Bhagavan commented, ‘Sivaprakasam has become the light of Siva’.

Prakasam means ‘light’, so this was a pun on his name.

jd: This suggests that he had achieved this second, final state.

DG: Bhagavan himself only gave public ‘certificates of enlightenment’ to his mother and the cow, Lakshmi. He did indirectly hint that other people had reached this state, but he would never name the names. He only named those two after they died.

jd: Let me ask this question differently. In the collective consciousness of the ashram and the people who are associated with it, are there certain people who, somehow, everyone agrees on? Are there people that everyone accepts as enlightened, even though Bhagavan didn’t publicly acknowledge their state?