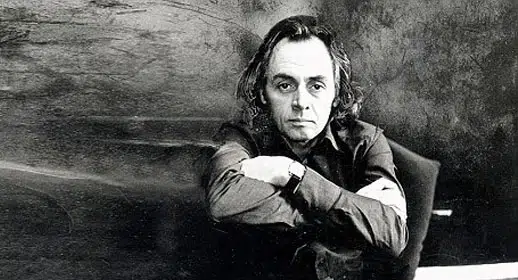

In 1965, the psychiatrist opened a residential treatment centre that aimed to revolutionize the treatment of mental illness.  Five decades on, those who lived and spent time there look back on an era of drama and discovery. The maverick psychiatrist RD Laing once described insanity as “a perfectly rational response to an insane world”. In 1965, having served as a doctor in the British army and then trained in psychotherapy at the Tavistock Clinic in London, Laing formed the Philadelphia Association with a group of like-minded colleagues. Their aim was to bring about a revolution in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.

Five decades on, those who lived and spent time there look back on an era of drama and discovery. The maverick psychiatrist RD Laing once described insanity as “a perfectly rational response to an insane world”. In 1965, having served as a doctor in the British army and then trained in psychotherapy at the Tavistock Clinic in London, Laing formed the Philadelphia Association with a group of like-minded colleagues. Their aim was to bring about a revolution in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.

“We aim to change the way the ‘facts’ of ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ are seen,” a later report-come-manifesto explained. “This is more than a new hypothesis inserted into an existing field of research and therapy; it is a proposal to change the model.”

From 1965 until 1970, as radical ideas and hippie ideals blossomed then died in cities across the globe, a former community centre in Powis Road in the East End of London became the unlikely setting for Laing’s most radical experiment in what came to be known as anti-psychiatry. “We have got Kingsley Hall and I have moved into it,” Laing wrote to his colleague, Joe Berke, when he was granted an initial two-year lease. “Others will be moving in in the next two or three weeks… I take it you will pass the word around to relevant people. THIS IS IT.”

The “relevant people” in question were other psychiatrists who shared Laing’s radical vision and their patients, though even the terms “psychiatrist” and “patient” would be upturned in the next few years at Kingsley Hall. At Laing’s insistence, the sprawling house became an asylum in the original Greek sense of the word: a refuge, a safe haven for the psychotic and the schizophrenic, where there were no locks on the doors and no anti-psychotic drugs were administered. People were free to come and go as they pleased and there was a room, painted in eastern symbols, set aside for meditation. There were all-night therapy and role-reversal sessions, marathon Friday night dinners hosted by Laing and visits from mystics, academics and celebrities, including, famously, Sean Connery, a friend and admirer of Laing’s. Play was encouraged as was regression through therapy to childhood. (Laing believed that all so-called madness began in the confines of the traditional family structure.)

The first, and subsequently most famous, resident inmate, Mary Barnes, regressed to infancy for a time, smearing the walls with her faeces, squealing for attention and being fed with a bottle. She later became an renowned artist, poet and, in 1979, the subject of a play by David Edgar. More controversially, several patients and workers were given high-grade LSD, which was still legal when Kingsley Hall opened, supposedly to release their inner demons or buried childhood traumas. At least two people jumped off the roof of the building. Its reputation, too, attracted drifters and dropouts and, at least once, the house was raided by the drug squad.

“It was a place that was very much of its time”, says the photographer Dominic Harris, who has tracked down several former colleagues of Laing’s and their patients, all of whom shared the turbulent, exciting and sometimes tragic experiment in communal therapy. “And it attracted maverick doctors, hippies, people running away from the draft, people trying to find themselves, as well as the seriously mentally ill. It was a time when everything was being challenged and people were allowed to be free in all kinds of ways. Kingsley Hall is seen as a very dangerous idea now by the medical establishment, but, back then, it was part of a greater social upheaval where definitions of authority, family, sexuality and illness were all being questioned.”

Harris first became aware of Kingsley Hall, which is just around the corner from his studio in Bow, when he read Jon Ronson’s book, The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry, in which Laing, who died in 1989, makes a fleeting appearance. Intrigued, Harris contacted Joe Berke, who put him in touch with a patient. Step by step, he tracked down other Kingsley Hall residents, visited them, photographed them and interviewed them. The result is a self-published photography book, The Residents, which includes Harris’s intimate portraits, pictures of the surviving but now disused house, as well as personal testimonies of those who were there.

“A lot of people, particularly Laing’s former colleagues, were initially a little bit suspicious of my motives,” says Harris, “but the patients were all very forthcoming. They haven’t really had a chance to tell their stories before as most of what has been written about the place concentrates on the incredibly charismatic figure of RD Laing. Nobody else has really had a voice. That is what the book is about in a way, letting the overlooked have their say. Laing is the underlying figure in the project, but it’s not about him. He’s the dead presence, the long shadow.”

Over two years, Harris managed to track down and meet 13 of the reputed 130 people who passed though Kingsley House in the five-year period. Their memories of the place are often impressionistic and contradictory, yet vivid and moving. They are all, to varying degrees, survivors of a radical, some would say irresponsible, moment when everything – even the definition of insanity and, by extension, sanity – seemed up for redefinition.

Pamela Lee: resident, 1967-68

‘I was given some LSD. I used to smoke cannabis, but I was a bit nervous about the acid’

Pamela Lee lived in another community house after leaving Kingsley Hall. She now lives in lives in north London and likes to make ceramic cats in a day class at the Mary Ward Centre

“Pamela was outstanding in a way, [because she was] totally normal,” remembers fellow resident Dorothee von Grieff. “She had this bourgeois furniture – it was so ordinary that it was such a contrast.” According to Francis Gillet, “she used to live on a bowl of brown rice and miso per day”.

I was just 10 when my father died and 17 when my mother died. My sister had left for London. I didn’t really have any family at all.

I had such a chaotic time in that period in London: so many addresses – there were 30 places in one year. It wasn’t my choice: I just used to get turned out of places. I went to a psychiatric hospital because I had a relationship with this guy I met, a medical student.

He invited me back to his parents’ and I think I was very, very nervous at the time – and shy. His parents thought I wasn’t very healthy.

I remember walking down the street when I was with him, and I felt on top of the world. I was imagining that all the people must be looking at me, thinking how wonderful and happy I was.

But then it ended, and it was like the end of my life, it was so awful. I went to the doctor’s and I said, “Can you send me to a convalescent home, I just can’t feed myself”, and they sent me to a mental hospital. It was very dictated to you what you could do: I was so disappointed.

I had picked up this book years before – [Laing’s] The Divided Self – and I realised that somebody really understood; it was amazing. So I phoned up and got an interview – I think it was in Harley Street – with Ronnie Laing, and he told me about this place [Kingsley Hall].

And that’s how I got there. It was like someone actually understood. Yes, I was really very impressed with Ronnie.

I remember that the people around us [local residents] didn’t actually like us very much. There was a very negative feeling towards us – not a very good community spirit. We were so isolated from the people around us, because if, they saw us, they would just ignore us. They really didn’t like us at all.

I was given some LSD when I was there. I used to smoke cannabis, but the acid I was a bit nervous about. I don’t think I actually took it.

I remember we used to eat together. The food wasn’t that good, actually.

Francis Gillet: resident 1966-70

‘Ronnie said, “Go mad, young man”. I took him at his word and went as mad as I possibly could’

Francis Gillet lived in Kingsley Hall as an unmedicated paranoid schizophrenic. Afterwards he lived in various other community houses. He now lives in sheltered accommodation in Oxford

I was a compulsive overdoser. If you showed me a bottle of pills, I’d swallow them all. Part of the problem was – and I’ve been reflecting on it lately – I was too young. I had too much life to live, and it was going to be so difficult to live it. I saw the road ahead as very long and very difficult, and it was. I mean, now I’m nearly 65, I don’t think that way because there isn’t so long to go and a lot of the hard work’s been done.

At the time I was at Kingsley Hall, the view really was that, if you had schizophrenia, it was no good talking to you because you would never get any sense out of a schizophrenic – it’s all nonsense that comes out of their mouths. And I pretty much subscribed to that view. Ronnie [Laing] said, “Go mad, young man”, and I did. I took him at his word, and I went as mad as I possibly could, and at no time did he try and stop me.

There were some very crazy people at Kingsley. There was one man who set up the dining table in the upstairs garden area, arranged it all for a dinner party and dressed up in white robes. I woke up one morning and there was the dinner table all laid in the garden and a man in a white robe gabbling to himself.

But I don’t think any of them were spotted by neighbours walking on the roof, as I was once. Yeah, [once] I leapt off the roof. I didn’t go the full drop. I leapt into a junkyard, which was full of old washing machines and Hoovers and things people had thrown over the wall. I got a crash fracture in my spine that still causes me problems today.

Ronnie used to keep acid in his fridge. It was pure stuff, Sandoz laboratory grade, the real McCoy, and he wasn’t shy about sharing it around. He believed it was a kind of spiritual laxative, which I think is probably quite an accurate description of it. And I do remember him handing it to me: I thought, ‘This is the apple from the tree of knowledge, and if I take this it’s going to be a long road back from where I’m going’, but I did take it. Ronnie did believe you would be able to flush demons away with it. I wouldn’t disagree, I think it’s an interesting thing.

[Then there was] the DMT – Dimethyltryptamine or ‘triptamine. It’s refined from a plant in the Amazon jungle and we had it shipped in from California in a briefcase. I took it once, and it changed my life for ever. Just once really blew my mind, and I never really thought the same about anything again.

A group of us at the Hall were interested in taking it. As soon as they injected it, we collapsed on to a bed; we couldn’t stand up. We were in a small room. I had a vision of myself as a dead Jew being bulldozed into a mass burial pit at Auschwitz. It was an intensely strong experience. It was the end of life, the end of existence. I felt very dead at that point.

[Another time], I remember meeting Sean Connery. He was at the height of his James Bond fame then. He came to a party with Ronnie, and the two of them started Indian wrestling while we stood around and drank. They went on and on wrestling each other in the games room. They decided to see which one was tougher – James Bond or Ronald Laing.

So that was all a wild party, but the next day he turned up at teatime and sat down, had a cup of tea and made it quite clear to us that he had been young once and he hadn’t had much himself and he could see himself in us and that kind of thing. He actually came back to thank us for having the party the night before. He was very humble and very nice.

Jutta Laing: resident, 1966-67

‘It wasn’t comfort, Kingsley Hall, that’s for sure. But it was an extraordinary group of people’

Jutta Laing was RD Laing’s girlfriend at Kingsley Hall and became his second wife in 1974. They had two sons and a daughter, but divorced in 1988. She now lives in north London where she teaches yoga

I came here because I wanted to get out of Germany. I had five names of people I might contact and I picked out RD Laing at random and called him. He invited me for lunch, and that’s how we met. He had left his wife and his children, and, although some people like to believe I took him away from his family, that’s not true at all because he had already had a liaison with someone else before me.

I worked freelance – with Gallery Five cards and doing illustrations for Harper’s Bazaar – and I did very well, but my life in Kingsley Hall and my life with Ronnie became predominant. It was a run-down place to live in, partly because there were quite a few very psychotic people living there who never washed or cleaned their rooms. Some people used it as a commune. A few hippies gravitated towards the place because it was very cheap to live there. Living there we had very little [free] time; we were always a group of people, maybe three, four, five people, looking after someone who had completely lost it, so they wouldn’t harm themselves.

For everyone who lived there, Kingsley Hall was an intense period, and my life with Ronnie was intense in the sense that a lot of people wanted to meet him. There were always visitors from all over the world. Ronnie was one of those people who you either loved or misunderstood. Some people thought he was crazy himself. Hid did drink a lot but he wasn’t a drunk. He was exceptionally alive and very charismatic. [The anthropologist] Francis Huxley labelled him a shaman.

It wasn’t comfort, Kingsley Hall, that’s for sure. But it was an extraordinary group of people. I live a quiet life now and have for quite a long time. I can’t say I have found the peace I am looking for.

Dorothee (Dodo): resident, 1966-67

‘Ronnie was a magician, a shaman. Such a place can’t exist without such a key figure’

Dorothee von Grieff came to London after finishing art school in Germany to “find herself”. She visited and lived in Kingsley Hall for the “experience”. An accomplished photographer, she took many pictures while she was there which largely remain unseen (see a selection above). She went on to study Tibetan Buddhism and now lives in north London

I was always looking for something in Germany, in my environment; I couldn’t find it. Germany was very controlling always and I rebelled and I didn’t want to rebel. I just wanted to live and to be myself. And that was an incredible liberation, that it happened, in a way, so dramatically, it was unexpected.

This incredible freedom in England and then in Kingsley Hall was just mind-boggling. Germany was so backwards: psychology didn’t exist or therapy, I mean that was something for loonies.

[At Kingsley Hall] it was open doors and no medication. That was totally revolutionary, that was the whole idea and it was incredible. That was in the Sixties, the big revolution, and for me Ronnie Laing’s skill was to hold up the mirror. He was a shaman, he had an incredible gift just to listen, to be in the present, to tune into the other person’s world and experience, and I had never met that before.

One memory: Mary Barnes had her room and one bathroom upstairs. When she was in the bath, it sounded like a whale, she had so much fun and made these incredible sounds and the bathwater came schlepping down the steps to her room. She had so much fun and screamed and yeah, it was like a whale and the water was coming down.

It was always quite a special day when she had her baths.

I was a helper: I cooked, I [helped] Jutta. But after a year I started to hear voices. It was hitting me. And then black magic came into the house, this dark energy. It just happened, and it wasn’t discussed. It was like a hippopotamus trampling through the house. It was so spooky I can’t tell you.

Before Ronnie and Jutta broke up – which was a very, very dramatic time for the whole community – and Ronnie had his breakdown, when everything fell apart – Kingsley Hall had already sort of subsided. But there was usually a continuity of meetings, music, getting together, rebirthing and so on.

[At one point] I came back from a trip to Germany and there was a meeting going on at the house among various members and it seemed to me like everything had broken loose. I mean, Ronnie was furious and roaring like a lion in pain. When Ronnie left that was when the disaster hit, because Ronnie [was] a magician, a shaman and an incredible being. It was a total downer. Ronnie was holding the place together. Such a place can’t exist without such a key figure, it can’t.

I was introduced to Tibetan Buddhism and [went on to] travel with my Tibetan teacher to Tibet and India. I mean, I couldn’t have gone on living in Kingsley Hall. It was 24 hours – it was non-stop and as I told you I was getting loopy.

James Greene: visitor 1966-68; resident 1968-69

‘He didn’t believe in the labels, patient versus helper; there was no demarcation’

James Greene, nephew of the author Graham Greene, was initially a patient of RD Laing. He then started training as a psychoanalyst. Greene informally oversaw the running of Kingsley Hall. He went on to become a translator of Russian poetry and a playwright. He lives in north London

Ronnie helped me to become a therapist. It was totally unorthodox but he didn’t believe in formal training for therapists – if he thought you were a suitable person to be a therapist, f*** the training. He didn’t believe in the labels, patient versus helper; there was no demarcation. The best thing that one could say about him is that he was a kind of shaman. If he’d stuck to being a shaman, OK, but he was also working officially as a psychoanalyst. You can’t really combine these two roles and he was full of contradictions. The people involved with him suffered as a result…

One patient had been in a mental hospital: John Woods, I think. His label in orthodox psychiatry was paranoid schizophrenic. He had some fantasy about some young woman and he couldn’t write letters to her himself so he dictated them to me. When it turned out this woman wasn’t interested, he assumed wrongly that I was preventing her from coming to visit him. He thought I was a black magician and was controlling her. Then living in there became quite scary. There was a chapel in the building, with a huge crucifix, and he burst into my room early one morning holding it. I thought he was going to attack me with it but he wanted to exorcise me. Eventually, I did something that was against the whole ideology of the place: I tried to have him sectioned.