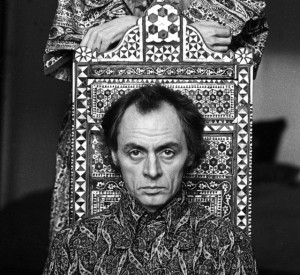

by Matthew Thornton: Those that pay heed to the writings, thoughts, and ideas of R. D. Laing may find themselves mystified. His ideas ran counter, and still run counter, to the established way of understanding and treating mental illness.  His life and work have been debated, idealized, and discounted. It seems that I rarely pick up a book in the field of family therapy that does not in someway have a fingerprint of Laing’s, either in the premise, approach, or at least lurking in the index and references.

His life and work have been debated, idealized, and discounted. It seems that I rarely pick up a book in the field of family therapy that does not in someway have a fingerprint of Laing’s, either in the premise, approach, or at least lurking in the index and references.

The psychiatric community has cried-out because of some of the drastic things Laing has done, but perhaps the most eccentric thing he ever did was to be human to a person dehumanized by all others (Signature, 1987). I have been intrigued by the work of Laing for several years. Intrigue, however, only serves if followed by inquiry.

Since I began my study in the field of family therapy, there have only been a few pioneers that have sparked and kept my attention. The list is short and includes R. D. Laing, Gregory Bateson, Milton Erickson, and Brad Keeney. As I survey the vastness of the ideas produced by this small group many, if not most of the ideas intersect. That of course is due to the mutual influence that each of these pioneers has had on the others, but for myself I have woven together as many strains of thought as I could grasp from this group to create the epistemological ideology from which I operate. These men are not all that have influenced me given I acknowledge the experiences of life that I have had to this point as also being interwoven into that epistemology along with countless lessons from countless teachers.

But the focus of my advanced study into the nature of human experience has largely emphasized the above mentioned. Each of these people has influenced the way in which I think and act, especially as a clinician. What I also find in common among these thinkers is not only ideas, but an enchanting presence of being. Even through their writings one can find the evidence of this presence or charisma. It is that presence that I am after. Laing was the first in which I began to notice this magnetism.

Who is R. D. Laing?

Ronald David Laing was a Scottish psychiatrist who worked successfully with people that suffered from psychosis of one form or another (Corey, 1991). He was a revolutionary thinker that questioned the controls that were imposed on the individuals by family, state, and society (Alic, 2001). His theoretical roots lie grounded in existential philosophy with influences by Husserl, Heidegger, Nietzche, and Sartre (Burston, 1998). The impact of his ideas and appreciation of his genius was only paralleled by controversy over what some felt was his madness. He was an accomplished pianist, a student of the classics, a rebel and a romantic, an iconoclast, a psychoanalyst, a philosopher, a theologian, and a drunk (Burston, 1996).

Some hold Laing with such esteem as to state that his impact on the field will be likened to that of Freud and Jung (Redler, Gans, Mullan, 2001). I believe the tolerance for Laing’s ideas has lessened because of the difficult message he brought to the field. Serious attention to his work has halted in recent years (Burston, 2000). Laing questioned the foundation on which the psychiatric community was based. He questioned the methods of diagnosis, treatment, and interventions used by those who had become the establishment. Laing questioned any person who believed that he had found the answer or who made a definitive statement regarding the whole of human experience. He wrote in his book, Politics of the Family and Other Essays, that in each case the theory or method of intervention must be discovered (1969).

R. D. Laing was born on October 7, 1927 in Glasgow, Scotland, and was later buried in the cathedral of that same town after his death in 1989 (Burston 1996). Laing was the only child of a working-class couple (Alic, 2001). Interested in the human mind since childhood, after grammar school Laing entered Glasgow University to study medicine and psychiatry (Alic, 2001). He earned his M.D. in 1951 and then served an internship in neurology and neurosurgery, after which he was drafted into the British army as a psychiatrist (Alic, 2001). During his two year term of service, it was said that he made friends with his patients rather than his fellow psychiatrists (Alic, 2001).

After his term of service Laing began work at the Gartnaval Royal Mental Hospital and taught in the Department of Psychological Medicine at Glasgow University (Alic, 2001). During this time he began working on his first book The Divided Self, which was not published until 1960. In 1956, he left there and began work at the Tavistock Clinic and the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London. He later stated that he was unhappy working at Tavistock and said that he felt, during this time, he went down the drain in his career (Burston, 1996). Laing then worked at the Langham Clinic for psychotherapy in London, where he practiced Jungian psychoanalysis from 1962 to 1965.

During his stay at Langham, he raised controversy over his use of psychedelic drugs, both with his patients and personally (Alic, 2001). In 1965 at Kingsley Hall in London’s East End, Laing co-founded an egalitarian community of patients and physicians. The clinic was closed after five years amidst controversy and rumors of outrageous behavior, though comparable communities still exist today (Alic, 2001). Laing also founded the Institute of Phenomenological Studies in London in 1967 as he continued on with a private practice (Alic, 2001). Laing’s career developed at a dizzying rate and was surrounded by controversy and debate over his theories, practices, lifestyle, and sanity.

All totaled, Laing authored 15 books, numerous articles, reviews, and forwards; was videotaped or audio taped giving lectures at conferences; and helped create videos such as “Did you used to be R. D. Laing?”. He was extremely committed to his projects, often to the degree of overextending himself to the breaking point. He dedicated his work to humanist concerns such as shedding light on the meaning of madness. He was constantly striving to stay open-ended and to challenge what most people take for granted. He was asked once what knowledge he would like to take to his grave, and he replied “I don’t feel obliged to believe anything—which doesn’t mean I don’t” (Bortle, 2000).

Thornton, Matthew (2005), I Used to Be You: A Metanoic, Refractive, Interpersonal Phenomenology Utilizing the Work of Ronald David Laing, M.D. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Louisiana Monroe]