by Joe Hunt: If he believed time existed, Akan Watts was way ahead of his…

What does a dead Episcopal priest from a small village in South East England know about what’s going on in the world today?

As trends in internet searches are showing more people are seeking out his many books, articles, videos, and audio recordings, apparently quite a lot.

Watts stands out among other 20th-century philosophers for several reasons. Namely, as angel investor James Beshara points out an episode of his podcast Below The Line, because he managed to do three unique things:

- Have very differentiated points of view from contemporary Western viewpoints.

- Articulate them extremely well.

- Do it all in a time when you could record your own lectures—which he did, in abundance.

Watts wasn’t an academic. He botched an opportunity for a scholarship to Oxford due to his shamefully “presumptuous and capricious” writing style.

He also wasn’t an expert in what he taught. Despite writing extensively about Eastern philosophies like Buddhism, Hinduism, Toaism, and Zen, he wasn’t ordained as any kind of monk or didn’t strictly follow any one system.

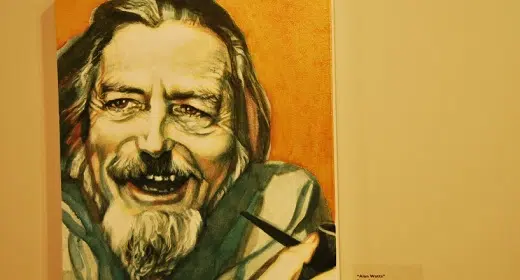

What he was, like the ideas he dedicated his life to studying and teaching, isn’t easy to define. He was a lover of life. He was a remarkable teacher during the 50s and 60s who, when questioned sharply by his students about what he was, settled with “spiritual entertainer”. He was a prolific writer, publishing over 25 books, most of which were, and continue to be, hugely successful.

Take that Oxford.

He also didn’t take life, or himself, too seriously. He enjoyed a good drink or six. He left the Church partly due to an extramarital affair. He didn’t pretend he wasn’t human and wasn’t ashamed of his vices—whether they be sex, alcohol, acid, partying on his houseboat, or all the above.

Along with the three reasons at the top of this article, for me, the main reason why Alan Watts is and will be the leading philosopher of the 21st century is that he clearly embodied everything he taught, and in doing so, wholeheartedly engaged in and enjoyed life.

His essential message, and the whole point and joy of human life, as he shared in the preface to his autobiography In My Own Way, was to “integrate the spiritual with the material”. He believed that this could only be done by carving “your own way”, by “accepting your own karma”, and by “following your own weird.”

So, that’s exactly what he did.

To try and lay out all of Watt’s teachings in one article would not only be impossible, it would be to do you and him a huge disservice. You have to watch, listen, and read Watts to be able to really grasp and experience what he has to teach.

I’ve gathered some of his main lessons to show how he and his teachings are key to addressing five of the most significant challenges of our age.

Lesson #1: On the meaning of life

“To know that you can do nothing is the beginning. Lesson One is: “I Give Up”… What happens now? You find yourself in what is perhaps a rather unfamiliar state of mind.” Just watching. Not trying to get anything. Not expecting anything. Not seeking. Just trying to relax. Just watching, without purpose.” — Alan Watts, Become What You Are

In the West, how much you know is the basis of wisdom. The more you know, the more you understand the world.

In the East, as Watt’s knew well, how much you know means diddly-freaking-squat. How much you don’t know, on the other hand — now that’s a sign of true wisdom.

“Get rid of knowledge; eject wisdom, and the people will be benefited a hundred-fold” — Lao-tzu

How can you understand the universe when you are a part of it? How can you discover the meaning of life through intellect alone? How can you bite your own teeth or eat your own mouth? Although seemingly obvious and even foolish, Watt’s believed such questions were key to really realizing how much we don’t know.

Overlooking such points when trying to understand life leads to an endless cycle of questioning, figuring out, problem-solving, and, ultimately, the only logical conclusion there is: that the universe is meaningless. As Watts states:

“If the universe is meaningless, so is the statement that it is so. If this world is a vicious trap, so is its accuser, and the pot is calling the kettle black.” — Alan Watts, The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety

When you take this conclusion as a negative end, you can spend eternity as a nihilist. But take it as a meaningful discovery and go beyond it, and you come to the profound realization that — Watt’s first and most important lesson — “I can do nothing”.

One can only attempt a rational, descriptive philosophy of the universe on the assumption that one is totally separate from it. But if you and your thoughts are part of this universe, you cannot stand outside them to describe them. This is why all philosophical and theological systems must ultimately fall apart. To “know” reality you cannot stand outside it and define it; you must enter into it, be it, and feel it. “ — Alan Watts, The Wisdom of Insecurity

You can’t make sense of the universe through problem-solving. You can’t find the meaning of life through thought alone. Problem-solving is a function of the universe. Your thoughts are one small expression of life.

From the beginning, the question was flawed. But more than that, trying to discover an answer or reason for existence, life, the universe, etc., as if you, the questioner, were separate from existence, life, the universe, will only serve to get you further away from finding what you’re looking for.

When you finally burn out or discard this futile seeking — and truly understand lesson one — as Watts puts it, “you see yourself as a purpose-seeking creature, but realize that there is no purpose for the existence of such a creature”.

Lesson #2: On uncertainty & insecurity

“To be secure means to isolate and fortify the “I”, but it is just the feeling of being an isolated “I” which makes me feel lonely and afraid. In other words, the more security I can get, the more I shall want”. To put it still more plainly: the desire for security and the feeling of insecurity are the same thing. To hold your breath is to lose your breath.” — Alan Watts, The Wisdom of Insecurity

Over 2500 years ago, Greek philosopher Heraclitus noted that, “the only thing that is constant is change”. Many of the world’s philosophies and religions of both East and West have come to a similar conclusion. Yet, there is a tendency is to believe that we as humans somehow stand apart from this rule.

“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”―Heraclitus

This belief, Watts argued, stems from the fundamental misunderstanding that humans are separate from the world around them. This misunderstanding permeates everything from everyday figures of speech: “You must face reality” “The conquest of nature.”, to how we think of ourselves as being born into the world:

“It is absolutely absurd to say that we came into this world. We didn’t. We came out of it.”

From the illusionary starting point, that you are a stranger that is born alone into an alien world, it’s an expected response to feel insecure and afraid. To grasp and try hold onto anything you can in an attempt to find security, safety, comfort, and connection.

But the more we search for these things, the more we only reinforce our own lack of them. The more we seek certainty, the more we feel uncertain. The more we want security, we more we feel insecure. The more we desire connection, the more we feel alone and separate.

“The more a thing tends to be permanent, the more it tends to be lifeless.” — Alan Watts

The problem isn’t that we lack these things in the first place. It’s that we tense up and try and resist the natural flow of life — its inherent uncertainty, insecurity, and impermenance. We attempt to exert control and will over it, and in doing so, achieve nothing but distancing ourselves further from it.

“Human life — and all life — does not work harmoniously when we try to force it to be other than what it is, for the very simple reason that this is based on the assumption that I, who would control things, am something apart from what I would control.” —Alan Watts, Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown (1968)

Avoiding this trap isn’t simply a case of brushing aside the desire for such things as security and certainty as if they aren’t worthy or real. As Watts says, “Calling a desire bad names doesn’t get rid of it.”

The desire is there for a reason. It is born from the chronic state of contraction or tension that is the root of the feeling we call “ego”, or, as Watt’s calls, “the marriage of an illusion to a futility”.

Deeply investigating this uneasy feeling, instead of futilely attempting to step outside of change, holding your breath against uncertainty, and ignoring the aching desire for connection, is where real certainty and connection is found:

If we can really understand what we are looking for — that safety is isolation, and what we do to ourselves when we look for it — we shall see that we do not want it at all.” — The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety

Lesson #3: On religion & faith

“Religions are divisive and quarrelsome. They are a form of one-upmanship because they depend upon separating the “saved” from the “damned,” the true believers from the heretics, the in-group from the out-group. . . . All belief is fervent hope, and thus a cover-up for doubt and uncertainty.” — Alan Watts, The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are

The problem that besets any doctrine or set of ideas that supposedly holds “The Truth” is, as Watts points out, is that it is based on believing that something is true, as opposed to knowing something is true for yourself.

Belief, as Watts explains, comes from the Anglo-Saxon root lief, which means to “wish.” Wishing implies a hope that things are true, and therefore an inherent lack of faith. But it also supposes that the thing you are believing in, whether God or Krishna or Allah, is or even could be separate from you.

“I rather feel that faith is an openness of attitude, a readiness to accept the truth, whatever it may turn out to be. It is a commitment of oneself to life, to the universe, to one’s own nature as it is, in the realization that we really have no alternative.” — Alan Watts, Zen and the Beat Way

Believing in some other entity that has divine power or will to save you from your sins can also cause you to close off from life and avoid its harsh truths — uncertainty, impermanence, death, change. Paradoxically, embracing such realities is essential for freedom and the basis of understanding any religion.

“The experience of pain is universal, and all religion starts from pessimism, for without the experience of pain in one form or another there will be no reflection on life and without reflection no religion.” — D.T. Suzuki, Ignorance and World Fellowship, 1936

Faith is an act of trust in the inevitably uncomfortable and uncertain unknown. When you distill religion into a few teachings or a book, it comes with the caveat that some people may use it in place of faith and cling to it as welcome relief from the unknown. As Watts explains:

“No considerate God would destroy the human mind by making it so rigid and unadaptable as to depend upon one book, the Bible, for all the answers. For the use of words, and thus of a book, is to point beyond themselves to a world of life and experience that is not mere words or even ideas.”—Alan Watts, The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are

Religion and spirituality have thus been separated from the rest of life and become “departments” of their own. Rather than being a mere department of life, Watts knew that religion “is something that enters into the whole of it.”

God is everything and nothing and everywhere and nowhere. By trying to cling to an idea of “God” via words or ideas, it is positively unfaithful because it closes the mind to everything else beyond that is not those words or ideas:

“Only words and conventions can isolate us from the entirely undefinable something which is everything.” — Alan Watts, The Wisdom of Insecurity

God can never be captured. Religion cannot be separated from everyday life. “The religious idea of God cannot do full duty for the metaphysical infinity,” as Watts describes in The Supreme Identity: An Essay on Oriental Metaphysics and the Christian Religion. The only way to experience God is to have faith in the unknown, to trust yourself to the flow, and just float:

“To have faith is to trust yourself to the water. When you swim you don’t grab hold of the water, because if you do you will sink and drown. Instead you relax, and float.”

Lesson #4: On Taoism & nature

“How does one bring oneself into accord with it [the Tao]?” “If you try to accord with it, you will get away from it”. For to imagine there is a “you” separate from life which somehow has to accord with life is to fall straight into the trap. If you try to find the Tao, you are at once presupposing a difference between yourself and the Tao.” —Alan Watts, Become What You Are

In the West, “nature” is something that’s equated with the countryside or the mountains — a place that is wild and out there.

Nature is thus something you enjoy from the safety of your couch via a David Attenborough documentary or when you finally get out of the city on the weekend.

This divide between our daily life and the natural world has grown so much that most of us don’t know where the food we eat every day comes from and feel out of place in the silence and vastness of open, cementless spaces.

In Chinese, the word for nature is ziran, which means “self so”, or “so of itself”. Ziran doesn’t mean green pastures over yonder. There is no word to distinguish between “us” and “nature” in Chinese. It means a spontaneous process that happens in and of itself.

This notion of ziran — the natural, spontaneous process of life — is the basis of the principle of “Tao”. The Chinese philosophy based around living in accordance with the Tao, and that is attributed to the person (or likely persons) Lao Tzu, is called Toaism.

“Lao-tzu didn’t actually say very much more about the meaning of Tao. The Way of Nature, the Way of happening self-so, or, if you like, the very process of life, was something which he was much too wise to define.”—Alan Watts, Become What You Are

Watts was one of the key figures in making Toaism accessible to Western minds. As he knew well, the Tao isn’t something that can be understood or even got at by mere explanations:

“For to try to say anything definite about the Tao is like trying to eat your mouth: you can’t get outside it to chew it. To put it the other way round: anything you can chew is not your mouth.”

According to Lao-tzu, you live in harmony with the Tao by doing nothing at all. But as Watts explains, doing nothing at all cannot be achieved by “deliberate imitation”, in which you suppose you know the right way to act. It’s also not possible through “deliberate relaxation”, where you relax your mind and try not to control yourself and think whatever the hell you want.

“There is no way, no method, no technique which you or I can use to come into accord with the Tao, the Way of Nature, because every how, every method, implies a goal.”

The only way to accord with the Way of Nature is wu-wei — non-striving, non-doing, or “action-less action”. The basis of wu wei is to engage fully in everything you do for nothing other than its own sake — i.e. without doing it to try and achieve some result, outcome, or other thing from doing it.

This doesn’t mean you go to work without an objective in mind and purposely ignore the future. That is to still be acting with another result — the result of not acting for results — in mind.

“If, then, we act, or refrain from action, with a result in mind — that result is not the Tao.”

There is nothing you can do to live more in harmony with nature and wu wei. Too much doing is what has created the divide between humans and everything else. The only thing you can do is give up trying to get somewhere else, and to recognize where and what you already are.

Lesson #5: On the present moment

“I have realised that the past and the present are real illusions, that they exist only in the present, which is what there is and all that there is. From one point of view, the present is shorter than a microsecond. From another, it embraces all eternity. But there isn’t anywhere, or anywhen, else to be.” — In My Own Way: An Autobiography by Alan W. Watts

How can you understand what you can never be understood? How can you be what you already are? How can you find the present moment?

Answering such unanswerable questions was Watt’s favorite pastime. What he discovered, and what is a core theme throughout much his work, is that such questions and pursuits are fundamentally flawed because they’re based on there being a you that’s separate to everything else to begin with:

“Without others, there is no self, and without somewhere else there is no here, so that — in this sense — self is other and here is there.”—The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are

Watts described this effort of trying to use one part of your “self” to try change or understand another part of your self, “trying to lift oneself up by one’s own bootstraps”. It’s a futile effort that can only go around in circles. It’s the arrow trying to shoot itself. It’s the ouroboros, the snake eating its own tail.

“To understand music, you must listen to it. But so long as you are thinking, “I am listening to this music,” you are not listening. To understand joy or fear, you must be wholly and undividedly aware of it. So long as you are calling it names and saying, “I am happy,” or “I am afraid,” you are not being aware of it.”—Alan Watts, The Wisdom of Insecurity

When the mind is split into an “experiencer” and something that is being “experienced”, it is caught in mind-made concepts and cannot be “wholly and undividedly aware” of what’s actually going on. There is a sense of an “I” that is trying to listen, understand, or achieve something. Once you become aware of this sense, the snake has begun to become conscious all the way around. Eventually, it will know its tail is the other end of its head, and you will have come full circle to see that “I” can do nothing at all.

“…the undivided mind is free from this tension of trying always to stand outside oneself and to be elsewhere than here and now. Each moment is lived completely, and there is thus a sense of fulfillment and completeness.”

Watts was fond of was comparing life to music and dance. Once you recognize the futility of trying to use one part of yourself to change another part, of striving towards spiritual ideas, of trying to get somewhere you already are, then life opens itself to be a purposeless, joyous, neverending dance.

It is a dance, and when you are dancing you are not intent on getting somewhere… The meaning and purpose of dancing is the dance.”

For, ultimately, the world of form and ideas that we take to be so real is nothing more than Lila—the “divine play” in Sanskrit. This doesn’t mean life isn’t to be taken seriously. Like a musician or dancer, you are free to fully immerse yourself in everything from rhythm and melody to discipline and pain, due to the very fact you know it is but a play.

According to Watts, seeing life as a dance is the secret to living a good life. He believed, we “only suffer because we take seriously what the gods made for fun.”

Watts has been the most influential person in my life, and no doubt that of many others. And his work is set to touch many more people in the coming decades.

For those that are interested, I’ve added a list below with all the books and resources I’ve quoted and drawn from for this article.

But I want to close by asking the question I started with once again: What does a small-town priest have to say about what’s going on in the world today?

Rather than having some pithy philosophical speech to make or something profoundly deep to say, I think what Watts might suggest is that we all need to chill the heck out and enjoy a bit more non-sense:

“Why do we love nonsense? Why do we love Lewis Carroll with his “‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe, all mimsy were the borogoves, and the mome raths outgrabe…”? It is this participation in the essential glorious nonsense that is at the heart of the world, not necessarily going anywhere. It seems that only in moments of unusual insight and illumination that we get the point of this, and find that the true meaning of life is no meaning, that its purpose is no purpose, and that its sense is non-sense.” —Alan Watts, Tao of Philosophy