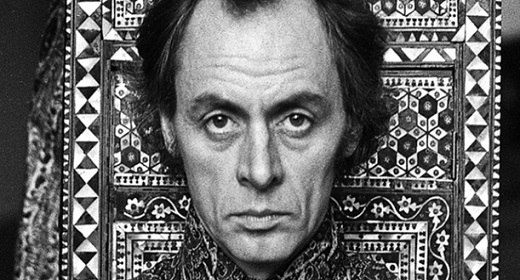

Ronald D. Laing‘s work was centered on understanding and treating schizophrenic patients…

He could perhaps best be termed an “existential psychiatrist.” Indeed, one of his early books was on Jean-Paul Sartre, and he used concepts from Sartre, Hegel and others in endeavoring to conceptualize the life and world of the schizophrenic. Laing himself grew up in a bizarre family setting. His parents forbid him to go out of the house alone or play with other children until middle childhood, they repeatedly conveyed the message to him that he was “evil,” and when he went out with them he was kept on a leash with a harness. His childhood environment was such as to cause him severe confusion about which thoughts and feelings were his own, and which were “mapped onto” him by his environment. As an adult, he was himself schizophrenic for periods of time, spending some time as a patient in psychiatric wards. As such, he gained a perspective on schizophrenia which was unusual and perhaps even unique for a psychiatrist. That is, he truly understood what the schizophrenic’s world looked like from the inside, as well as from the outside. He also had gained, from his own experience, a sense of the kind of situations in family, school, etc., that could drive a person crazy.

A sane response to an insane situation. This is Laing’s comment about what “going crazy” entailed. Applying Gregory Bateson’s concept of the double bind, in which anything a person does leads to one or another kind of punishing consequence, he observed that some children are faced with the dilemma of having an identity defined for them that is fundamentally different from who they experience themselves to be. Their alternatives are to either give up the parental approval and caretaking they need to survive, in order to be truly themselves, or to give up their own sense of their identity and comply with parental demands. Faced with this dilemma, most people choose to give up their own identities and adopts those that are handed to them by parental figures. In some people faced with this situation, the response is to “go crazy.” This is analogous to being inside a tunnel which represents what are normally considered “sane” thoughts, actions, and feelings, finding that moving in either direction leads to painful experiences (giving up self, or giving up the other), and in response breaking through the ceiling of the tunnel into what is considered insanity. (I think, although I am not certain, that this analogy is mine rather than Laing’s.)

Interest in the subjective experience of the schizophrenic. Given his own background, Laing was able to perceive how pathetically limited and inadequate the conventional psychiatric definitions of schizophrenia are. They are largely “looking at” from outside, and capture little of the schizophrenic’s own experience. Laing tried to capture the structure of the schizophrenic experience in “The Divided Self,” written when he was only twenty-eight years old. Later he would characterize that early work as too much in an “us-them” mode. His later work explored the nature of relationships and the workings of schizophrenogenic families. He also included many observations on the way in which school and other social institutions imprison both children and adults in situations that confuse them about their own thoughts and feelings, induce them to think they have the socially approved thoughts and feelings that others want them to, and as a consequenc drive them crazy.

Treatment of the schizophrenic. Laing established a treatment facility in a London suburb which housed, I think, about fifteen or twenty schizophrenic patients and several live-in psychiatric staff persons. (I’m not sure about that number.) Patients were given no drugs, They were provided with support in the form of daily group therapy, individual therapy, and ongoing interaction with staff. Staff members were careful to accept the subjective validity of the schizophrenic’s experience of the world. In addition, there was reality-testing in the form of feedback from other group members. No drugs were administered. In Laing’s view, drugs make it more difficult for a person to think and therefore interfere with the kind of personal work that can lead to true recovery. I read one case history of a member of the psychiatric staff who shared a room with one patient who defecated in the room and often screamed apparently uncontrollably. Laing’s approach took the existential view that each person, including the schizophrenic is ultimately responsible for his or her own behavior, and ultimately his or her own recovery. He viewed his role as that of providing conditions that would facilitate that recovery. For a time there were a number of treatment facilities around the world that followed the Laingian model. To the best of my knowledge, today it has been largely abandoned, both because it is very expensive in terms of professional time and effort and drugs are cheaper and can be administered by poorly paid ward personnel, and because the psychiatric establishment is committed to a medical model rather than an existential model.

The situation has to be discovered: “We can never assume that the people in the situation know what the situation is. There is no a priori reason to believe or disbelieve a story anyone tells us. Different people usually have different stories about a situation. A psychiatric “history” of the situation is a sample of the situation. It is a story, one person’s way of defining the situation. “Few psychiatrists are experts in sorting out these stories. They are experts in construing situations of a few standard psychiatric myths.” (politics of the family, p. 33-4)

Family resistance: Laing notes that he often finds that what he thinks is going on in a family bears almost no resemblance to what anyone in the family expriences or thinks is happening. Often “there is concerted family resistance to discovering what is going on, and there are complicated strategems to keep everyone in the dark.” (politics of the family, p. 77)

Metaphors for a family. “The family may be imagined as a web, a flower, a tomb, a prison, a castle,” writes Laing. We may be more aware of our image of the family than of the family itself.

Complementarity: “That feature of relatedness whereby the other is required to fulfill or complete the self.”

Confirmation: Some sign of recognition by another person that is relevant to an evocative act. This may include disapproval. “Every relationship. . . implies a definition of self by others and other by self. . . A person’s ‘own’ identity can never be completely abstracted from his identity-for-others.” (Self and Others)

Pseudo-confirmation. Acts that masquerade as confirmation, but are counterfeit. For example, I define who you are, then confirm your behavior and being that conforms with my definition.

Tangential responses: Those that deal with some aspect of a person’s behavior other than those the person is concerned with.

Mystification: Misdefinition of the issues. A plausible misrepresentation of what the exploiters do to the exploited.

The situation has to be discovered: “We can never assume that the people in the situation know what the situation is. There is no a priori reason to believe or disbelieve a story anyone tells us. Different people usually have different stories about a situation. A psychiatric “history” of the situation is a sample of the situation. It is a story, one person’s way of defining the situation. “Few psychiatrists are experts in sorting out these stories. They are experts in construing situations of a few standard psychiatric myths.” (politics of the family, p. 33-4)

Mapping: A person “maps” some accepted social definition of reality onto his or her experience and then acts as if that map reflects his or her experience. Or else feels terribly oppressed and unseen, if the personal experience is very different from the “mapped” pseudo-experience.

“Call experiential structure A, and public event B. Sometimes the product of A and B, in a marriage ceremony, is a marriage. Both people are married in all senses at once. . .

“One function of ritual is to map A onto B at critical moments, for example births, marriage, deaths. In our society many of the old rituals have lost much of their power. New ones have not arisen.

“To preserve convention, there is a general collusion to disavow A when A and B do not match. Anyone breaking this rule is liable to invalidation. One is not supposed to feel married if one has not been married. Conversely, one is supposed to feel married if one ‘is.’ If one goes through a marriage ceremony, and does not feel it is ‘real’, if it dod not ‘take’, there are friends and relative s to say: ‘Don’t worry, I felt the same, my dear. Wait until you have a child. . . Then you will feel you are a mother,’ and so on. . . .

“So one feels, perhaps, frightened or guilty, and probably wishes to disavow A; to take refuge in B, where everything is as everyone says.” (politics of the family, p. 69)

Delusional structures involve a severe mismatch in mapping. In very disturbed people, one finds what may be regarded as delusional structures, still recognizably related to family situations. The re projection of the ‘family’ is not simply a matter of projecting an ‘internal’ object onto an external person. It is superimposition of one set of relations onto another: the two sets may match more or less. Only if they mismatch sufficiently in the eyes of others, is the operation regarded as psychotic. That is, the operation is not regarded as psychotic per se.

Induction: Projection is done by one person as his own experience of the other. Induction is done by one person to the other’s experience. One does not tell him what to be, but tells him what he is. Such attributions, in context, are many times more powerful than orders (or other forms of coercion or persuasion.)” One is told one is good, bad, evil, pretty, sexy, etc.

“When attributions have the function of instructions or injunctions, this function may be denied, giving rise to one type of mystification, akin to. . . hypnotic suggestion.”

One may tell someone to feel something and not to remember he has been told. Simply tell him he feels it. Better still, tell a third party, in front of him, that he feels it.”

What the parents tell a child “he is, is induction, far more potent than what they tell him to do. . . . These signals do not tell him to be naughty; they define what he does as naughty. In this way, he learns that he is naughty, and how to be naughty in his particular family.”

“It is not sufficient to say that my wife introjects my mother, if by projection, and induction, I have manouvered her into such a position that she actually begins to act, and even to feel, like her, [perhaps] without ever having met her.” (Politics of the family, 78-9, 119-20))

In induction the family members seldom know what they are doing. “Often the parents are themselves confused by a child who does x, when they tell him to do y and indicate he is x. “I’m always trying to get him to make fmore friends, but he is so self-conscious. Isn’t that right, dear?”

Paradoxical orders: If correctly executed, they are disobeyed. If they are disobeyed, they are obeyed. “Be spontaneous.” “Don’t do what I tell you to.”

We have rules against knowing certain rules. “Rule A: Don’t. Rule A1: Rule A does not exist. Rule A2: Rule A1 does not exist.”

Domain and range. “One can project a minute domain onto a vast rainge; or a vast domain onto a minute range. Scale is no deterrent in practice.”

Psychiatrists as mind-police: “If a and B are incongruent, the mind police (psychiatrists) are caleled in. A crime (illness) is diagnosed. An arrest is made and the patient taken into custody (hospitalization). Interviews and investigations follow. A confession may be obtained (patient admits he is ill, displays insight). . . . The sentence is passed (therapy is recommended). He serves his time, comes out, and obeys the law in the future.” This is how the “official story of psychiatric consultation, examination, diagnosis, prognosis, treatment. . . is often experienced.” (politics of the family, p. 74)