bySimon Thibault: It could feed a ballooning population and help the environment, but that may not be enough to get people to eat it…

Seaweed covers the beaches you walk on, it’s dried in your instant miso packets, and researchers in labs all over the world are studying it. Scientists, food companies and environmental advocates want you to eat more of the product ― sometimes more appealingly titled “sea vegetables.” But those who grew up in Western households may not think too highly of seaweed as a food.

Jonathan Kauffman, author of Hippie Food, says that may be in part because of how Westerners were introduced to it ― as a health food eaten by “hippies” in the 1960s. “Seaweed never made much of an impression on the broader public, who mostly lumped it in with other weird health foods they were writing off,” he says.

According to him, other than people who extolled the nutritional virtues of seaweeds, such as those who followed macrobiotic diets, sea vegetables weren’t much of a pantry staple. ”My guess is that the flavors were too oceanic and the texture too gelatinous for eaters who didn’t grow up eating seaweed.”

But seaweed’s star is ascendant. The global seaweed market is expected to be worth $9 billion in the next six years, with most of that coming from its use as a food, particularly in Asia-Pacific countries such as Japan. While Westerners have been much slower to adopt seaweed into their diet, that’s expected to change as consumers become more familiar with it and the hype grows around its potential nutritional, health and environment.

The names Kauffman uses in talking about the varieties of sea vegetables showcase how many of us first encounter them today: in Japanese and East Asian cuisines. Nori wraps your sushi, hijiki may be the crunchy tendrils in your seaweed salad, and you’d be hard-pressed not to find small soft bits of wakame in your bowl of miso.

But Nancy Singleton Hachisu would argue that you’re missing out if that’s all you think there is to the culinary possibilities of sea vegetables. The California native has been living in Japan for 20 years and writes about Japanese food. One of sea vegetables’ selling points, Hachisu says, is their shelf life. Hachisu’s approach to introducing westerners to sea vegetables is to start simply, and to use it as a building block of flavor, such as in dashi, a clear savory stock made from a kelp known as konbu in Japan.

Seaweed has been given the ubiquitous and generally meaningless label of “superfood.” But there is research into its potential health benefits, which are said to range from better heart health to contributing to an increased life expectancy. Chigozie Okolie and Dr. Beth Mason from Cape Breton University in Nova Scotia, Canada, are looking into the potential of sea vegetables to benefit our gut, for example.

“Dietary fibres from seaweeds have been scientifically proven to act as prebiotic i.e. food source for beneficial gut microbes,” Okolie said in an email. He believes that an increased interest in looking at seaweed in diets comes from the sustainability credentials of the plant compared to foods from land-grown plant sources.

Seaweed is being talked up as a wonder food for its environmental benefits. As the global population grows ― it’s expected to reach 10 billion by 2050 ― so too does demand for food. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization has estimated we will need to increase food production by 70 percent between 2007 and 2050. This places pressure on land and freshwater resources at a time when scientists say climate change is already increasing the extreme weather events that disrupt agriculture.

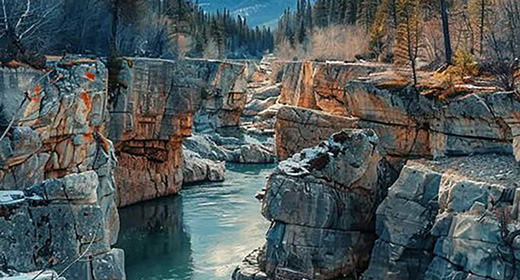

In this context, advocates say seaweed offers a near-perfect solution. It requires no fertilizer or freshwater to grow, it sucks climate-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and also helps counteract ocean acidification. It is fast-growing, too, seeing around 30 to 60 times the growth rate of land-growing plants, according to Australian scientist Tim Flannery.

Thierry Chopin is a professor of marine biology and director of the Seaweed and Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture Research Laboratory at the University of New Brunswick in Canada. Chopin’s work has focused on creating sustainable marine systems where salmon, shellfish and seaweed grow together. As well as absorbing carbon, says Chopin, seaweed helps recycle excess nitrogen and phosphorus from fish feces that otherwise cause water pollution. He sees seaweed as an anchor in fostering balance ― economically as well as environmentally.

Chopin is also exploring potential medicinal applications. His work takes him to the Bay of Fundy, where the temperature of the water varies from about -35 to 99 degrees Fahrenheit. The seaweed has to withstand that, he says, “which means the seaweed must be very well-equipped to protect its proteins.” It is the study of those mechanisms that Chopin hopes will lead him to possible treatments for Parkinson’s disease, a neurological disorder that is caused by a degradation in how certain proteins in the body function.

Not everyone is so unequivocal about seaweed and its appeal, however. In Cape Cod, Tamar Haspel is trying to think beyond the medicine cabinet, the pantry and the environment to explore whether North Americans will actually embrace seaweed as food. Haspel is an oyster farmer who also writes the James Beard Award-winning Unearthed column in The Washington Post that covers food supply issues.

When it comes to sea vegetables, she is of two minds: We should grow it, but don’t magically expect us to start eating it in droves. In a 2015 column, she wrote that the taste of seaweed is “a bit of a hurdle. Seaweed is, unfortunately, not delicious.”

For Haspel, it comes down to consumer choices, and those choices are guided by what we perceive as tasting good. “If there is one fundamental truth about the American diet it’s that we should eat more vegetables,” she pointed out in an interview over Skype. “But if you look at consumption, it has flatlined since the ’70s. If we can’t get people to eat vegetables, how are we going to convince them to eat [sea] vegetables? People consider taste, price and their own personal health, in that order.”

Haspel is sympathetic to the arguments that growing sea vegetables is good for the oceans, as she herself works by and with the ocean. But she doesn’t believe ecological considerations are going to put kelp on your plate. “That’s not a problem for consumers,” she says. “It’s a supply chain problem.”

She argues that the onus may have to fall on big food companies to supply consumers with packaged products ― with better nutritional profiles ― to get them into it. However, she says, it won’t be easy. “The truth of seaweed and the American diet is that people like to be sold things that are delicious.”