by Jeff Warren: The Neuroscience of Awakening…

It was 1972 at Penn State University, and Gary Weber, a 29-year old materials science PhD student, had a problem with his brain. It kept generating thoughts! He had a continuous and oppressive stream of neurotic concerns about his life, his studies, and everything else. While most human beings would consider this par for the course; par for the human condition (or ‘cogito ergo sum’, which can be translated as “I think therefore I am”), Weber wouldn’t accept it. He was a scientist, a systematizer, a process guy. He liked to figure out how things worked, and how they could be tweaked to work more efficiently. And at that moment his brain wasn’t very efficient. It expended a lot of energy going over and over the same anxieties, and cravings, and storylines. “Most of these thoughts had no purpose,” he said. “They were not going to cure cancer.”

It was 1972 at Penn State University, and Gary Weber, a 29-year old materials science PhD student, had a problem with his brain. It kept generating thoughts! He had a continuous and oppressive stream of neurotic concerns about his life, his studies, and everything else. While most human beings would consider this par for the course; par for the human condition (or ‘cogito ergo sum’, which can be translated as “I think therefore I am”), Weber wouldn’t accept it. He was a scientist, a systematizer, a process guy. He liked to figure out how things worked, and how they could be tweaked to work more efficiently. And at that moment his brain wasn’t very efficient. It expended a lot of energy going over and over the same anxieties, and cravings, and storylines. “Most of these thoughts had no purpose,” he said. “They were not going to cure cancer.”

It so happened that shortly after he recognized the problem, in one of those little life coincidences that some people like to call ‘synchronicities,’ Weber picked up a slim volume of poetry on his way out of the library. He sat down on the green grass in front of the University admin building, unpacked his lunch and idly opened the book. He read:

All beings are, from the very beginning, Buddhas. – Haikuin Ekaku

This is the first line of a famous Zen poem – Song of Zazen – written in the 18th century by the Japanese Buddhist teacher Hakuin Ekaku. Weber knew nothing of Zen. Still, within seconds of reading Ekaku’s words, according to Weber: “the entire world just opened up. I mean it literally opened up. For what must have been thirty or forty minutes, I dropped into this magnificent expansiveness – a vast empty space without any thoughts whatsoever.”

Weber had had what in Zen is called a ‘kensho’ – an awakening; a glimpse into the unconditioned, a mystical phenomenon described in different ways by countless texts and countless teachers, in countless traditions. It was a profound experience, but like so many such experiences, it didn’t last. Weber’s thoughts returned – as insistent and clamorous as ever. But now Weber knew another way was possible. He was determined.

A Spiritual Life in a Scientific World

For the next 25 years, as Weber finished his PhD; married and raised two kids, and made his way through a string of industry jobs – eventually culminating in a senior management position, running the R&D operations of a big manufacturing business – he got spiritual. He read lots of books, he meditated with Zen teachers, mastered complicated yoga postures, and practiced what is known in Vedic philosophy as ‘self-inquiry’ – a way of directing attention backwards into the center of the mind. To make time for all this, Weber would get up at 4am and put in two hours of spiritual practice before work.

Although he says he never had the sense he was making progress, Weber kept at it anyway. Then, on a morning like any other, something happened. He got into a yoga pose – a pose he had done thousands of times before – and when he moved out of it, his thoughts stopped. Permanently. “That was fourteen years ago,” says Weber. “I entered into a state of complete inner stillness. Except for a few stray thoughts first thing in the morning, and a few more when my blood sugar gets low, my mind is quiet. The old thought-track has never come back.”

Of course, the fact that Weber is telling this story at all would seem to contradict this rather dramatic claim. Conventional wisdom tells us that talk is the verbal expression of thinking; separating the two makes no sense. And yet, this is the experience Weber reports. And at the time he didn’t care if it was theoretically impossible. What he cared about was that in an hour he needed to go to work, where he was supposed to run four research labs, manage a thousand employees, and a quarter of a billion dollar budget, and he had no thoughts. How was that going to work?

“There was no problem at all,” Weber says, which he admits may say more about corporate management than about him. “No one noticed. I’d go into a meeting with nothing prepared, no list of points in my head. I’d just sit there and wait to see what came up. And what came up when I opened my mouth were solutions to problems smarter, and more elegant than any I could have developed on my own.”

Over time, Weber figured out that it wasn’t that all his thoughts had disappeared, rather, a particular kind of self-referential thinking had cut out what he calls “the blah blah network.” Scientists now refer to this as the “default mode network” (DMN), that is, the endlessly ruminative story of me: the obsessive list-maker, the anxious scenario planner, the distracted daydreamer. This is the part of the thinking process we default to when not engaged in a specific task.

“What’s fascinating to me,” Weber says, “is I can still reason and problem solve, I just don’t have this ongoing emotionally-charged, self-referential narrative gobbling up bandwidth.”

But the real surprise for Weber is what disappeared along with the “me” narrative: any sense of being a separate self, and with it, all mental and emotional suffering. He has a theory about this: “If you look at the self-referential narrative, it’s all ‘I, me, mine.’ When that cuts out, the ‘I’ goes with it. Now, for me, it’s very quiet and peaceful inside – there’s no sense of wanting things to be other than they are, and no ‘I’ to grab hold of ‘I want, I desire, I lust.’” Although his case is extreme, Weber’s experience is in line with research showing that more DMN activation correlates with more unhappiness – ‘A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind’, as the title of one well-known paper puts it.

Weber has even found the changes have carried over into his emotional life: “I still get angry, but it’s different now. If someone cuts me off in traffic, I feel the energy come up, but it doesn’t go anyplace. There’s no chasing somebody down the highway. The anger dissipates immediately – it doesn’t carry forward. You don’t lose the typical neural responses – thank goodness – what you lose is the desire leading up to them, and, once the response passes, you don’t make up a story about what happened that you repeat again and again in your head. Those storylines are gone.”

The Brain Exploration Begins

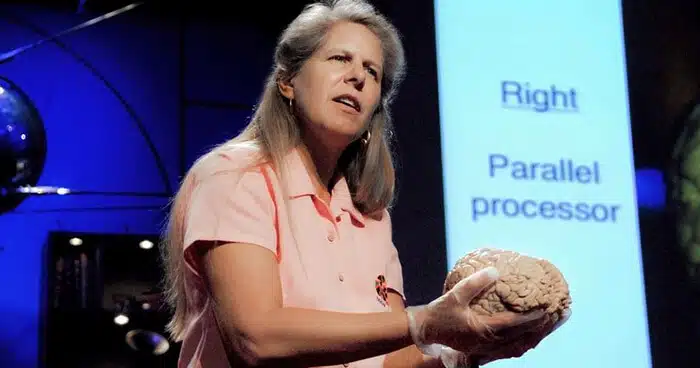

Like other scientists before him who’ve experienced similar transformations – the neuroscientist James Austin, the neuroanatomist Jill Bolte Taylor, to name two examples – Weber got interested in what was going on his brain. He connected with a neuroscientist at Yale University named Judson Brewer, who was studying how the DMN changes in response to meditation. He found, as expected, that experienced meditators had lower DMN activation when meditating.

But when Brewer put Weber in the scanner he found the opposite pattern: Weber’s baseline was already a relatively deactivated DMN. Trying to meditate – making any kind of deliberate effort – actually disrupted his peace. In other words, Weber’s normal state was a kind of meditative letting go, something Brewer had only seen a few times previously, and other researchers had, until then, only reported anecdotally.

And here we come to a subtle but important difference of opinion between Weber and Brewer. For Weber, true letting go means arriving at a state of “no-thought” where the mind is permanently stilled of any kind of “bandwidth-gobbling” inner monologue. Creative thoughts, planning thoughts – these are fine, and are, according to Weber, served by completely different parts of the brain. The real suffering happens in the endless and exhausting internal monologue. Thus, he argues, working to extinguish these kinds of thoughts should be the explicit goal of practice, something he says other contemplative traditions also emphasize.

By contrast, further study has suggested to Brewer that the thoughts themselves – even a certain amount of the self-referential kind – may not actually be the problem; the real problem is our human tendency to fixate and grip and get “caught up” in these thoughts. Some of his subjects attained dramatic reductions in DMN activity, while still thinking in a self-referential way. They just weren’t attached to their ruminations. One subject described watching his thoughts “flow by.” As Buddhists have long argued, you don’t need to eliminate the self-thinking process, you just need to change your relationship to it.

Whatever the exact case, both men agree that a reduction of activity in the DMN is central to the elimination of suffering. That it is being discussed at all marks an important advance in the scientific study of meditation in particular, and spiritual practice in general. Many researchers have shown unequivocally that stress and suffering can be dramatically reduced by meditation and by mindfulness in life. But they have not yet shown why this is so.

Have Brewer and his colleagues finally found a clue to how the reduction of suffering looks in the brain? Not the activation of a specific region, but a more general deactivation; a neurological “letting go” that parallels the experiential one? “Even in novices we saw a relative deactivation across the brain – like the brain was saying, “Oh thank God I can let go. I don’t have to do stuff; I don’t have to do all this high energy maintenance of myself”. One interpretation of that – and there are many others – is that the brain knows what it needs to do. It’s a very efficient machine; we just have to stop getting in the way.”

This kind of neurobiological perspective is a movement towards what Brewer calls “evidence-based faith,” where science may be able to help teachers and practitioners fine-tune the approaches they take to practice. Contemplatives may recoil at the idea, but for Brewer, addressing suffering is the priority; a project science can help with. As proof-of-concept, Brewer has just published two studies that show how meditators can watch live feedback from their brains inside the fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and use it to decrease their DMN activation in real-time. And he’s just received an NIH grant to study how this could work for non-meditators more quickly, and hopefully one day, more affordably. “The aim is to see if neurofeedback can give regular folks feedback on subtle aspects of their experience …stuff they wouldn’t notice otherwise.” he says.

Weber agrees, “Right now we can get folks off the street, and within one or two runs in the Yale fMRI, they can produce this deactivated state. The more glimpses the brain gets, the more time it spends there, the more it can stay there. It’s like riding a bike. With this technology you may not have to spend twenty-five years practicing like I did. It’s much more efficient.”