Women are barred from ordination in Thailand’s Theravada Buddhist sect. After Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni was ordained in Sri Lanka, she set out to elevate women’s religious status in her Thai homeland.

At the Songdhammakalyani Monastery in Nakhon Pathom, an hour outside Bangkok, six bhikkhunis, or nuns, dressed in saffron colored robes, begin the day with a morning prayer.

Adhering to the practices of the Theravada school of Buddhism, the bhikkhunis keep a strict timetable, getting up at 5 a.m. to chant, meditate, study religious scriptures and collect alms from the surrounding villages.

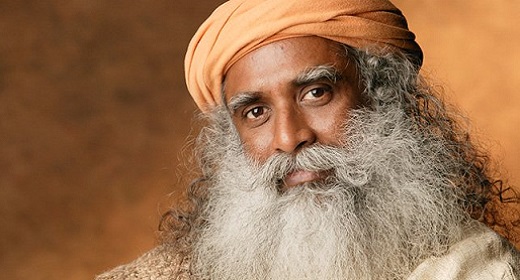

This temple is like thousands of others across the country, except it is the only monastery in Thailand with ordained nuns. Here, Venerable Dhammananda Bhikkhuni is the temple’s abbess, or superior nun.

Dhammananda is now in her late 60s. Her interest in Buddhism stemmed from her mother, who helped establish the monastery in 1960. It was the first of its kind to be built by women, for women.

Dhammananda is the first Thai woman to fully ordain in the Theravada monastic lineage

“This was my mother’s idea,” Dhammananda said. “When my mother had had enough of her lay life, she decided to be ordained.” Dhammananda was 10 years old at the time her mother sought ordination – abroad.

No suppor for female ordination

In the 1950s, Dhammananda’s mother, Venerable Voramai, was prohibited by the local conservative clergymen to become a bhikkhuni, as the tradition of ordaining women had been lost in the Thai Teravada tradition. Women were supposed to lead a life as lay people, serving monks, but not become nuns. In other Asian countries, like Vietnam, Tibet or Taiwan, where the Mahayana tradition is prevalent, the tradition of ordaining Buddhist nuns had been common practice for centuries.

Voramai believed nuns should engage in social service, as well as following their spiritual path. It was that pioneering spirit that inspired her daughter, Dhammananda, who initiated her career in academia but later found a different path.

Residents offer food as alms to the monastery

For three decades, Dhammananda was a professor of religious studies and philosophy at Thammasat University in Bangkok. She published books on women and Buddhism and even had a television show called “Dharma Talk,” which gained national popularity and won several awards.

But then her focus changed. “I’d had enough of the success,” Dhammananda said. “I had enough of this worldly life. Where was it leading?” she asked herself one day with a feeling of discontent. That’s when she decided to walk down her mother’s path and seek ordination.

Promoting equality

Just as her mother became the first modern Thai woman to become a nun in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, Dhammananda became the first to take Theravada nun vows in a ceremony in Sri Lanka. Theravada Buddhists there had since managed to re-establish female ordination.

After her ordination, Dhammananda began promoting religious equality for bhikkhunis in Thailand.

When her mother became interested in Buddhism, Dhammananda told DW, “she realized that when Buddha was alive, [he] ordained women, even his own mother.” That suggests female ordination goes back some 2,500 years, to the early days of Buddhism. She began asking herself why women in Thailand had been deprived of the right.

Female ordination is permitted under the current Thai constitution. But the Thai Sangha Council, a conservative religious advisory group, remains hostile toward bhikkhunis, believing only men can enter the monkhood. This underscores an already alarming gender inequality problem in Thailand.

It is widely accepted among Buddhists that the Buddha established the “Four Pillars of Buddhism” – consisting of monks, nuns, lay men and women – to uphold the religion. In Thailand, however, bhikkhunis were removed from the Thai Sangha law since the word “sangha” – which means monastic community – was defined as “bhikkhu sangha.” This male-centric wording thus excludes women. Despite these difficulties, Dhammananda is trying to bring about larger structural change by building a community of female monastics, paving the way for other women to ordain and be ordained.

Strengthening women’s calling

Throughout Thailand there are currently more than 30 bhikkhunis living in monasteries. In some cases women seeking ordination have been accused of impersonating monks, a civil offense in Thailand. Without legal recognition bhikkhunis are not respected by Thai authorities and are denied various benefits enjoyed by their male counterparts.

“You have a hospital for bhikkhus but you don’t have a hospital for bhikkhunis, and what about if a bhikkhuni gets sick?” said religious scholar, Sutada Mekrungruengkul, a lecturer at Nation University in Lampang. “Bhikkhus have their own university, but there is no university for women. Bhikkhus also receive a monthly government pension.”

A distinguishing characteristic of the Songdhammakalyani Monastery is that it offers women access to Buddhist education.

“Since I’ve become a bhikkhuni I’ve learned to control myself, to know myself. I didn’t know myself before,” said 53-year-old Dhammasiri, who was ordained four years ago.

Dhammananda has empowered women from all walks of life to follow in her footsteps

“As a former religious scholar, Venerable Dhammananda’s feminist approach to religious texts is very empowering,” Dhammasiri said. “Unlike the monasteries that are male-dominated, she is able to give us the Dhamma of the Buddha from a woman’s perspective.”

Dhammananda believes that re-establishing the bhikkhuni sangha in Thailand is a spiritual responsibility in order to maintain the Buddhist tradition. She considers being fully ordained the rightful heritage of women.

“Women have always been contributing to Buddhism. And it is actually women who feed the monks,” Dhammananda explained. “You go to any temple in Thailand, 80 percent of the attendants are always women, so they are actually the foundation to upkeep the goings of Buddhism in this country.”