by Mark Matousek: What do spiritual masters know about the mind?

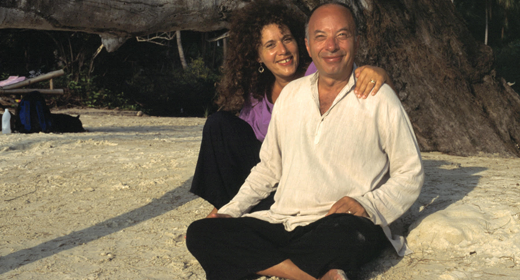

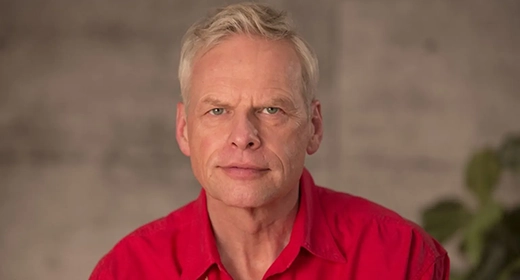

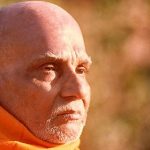

Adyashanti is an American-born spiritual teacher devoted to serving the awakening of all beings. His teachings are an open invitation to stop, inquire, and recognize what is true and liberating at the core of all existence. He is the author of The Way of Liberation, Falling into Grace, True Meditation, and Resurrecting Jesus: Embodying the Spirit of a Revolutionary Mystic. I’ve done a number of retreats with Adya who is in my estimation one of the three truly original spiritual thinkers of our moment, the other two being Eckhart Tolle and Byron Katie. We had a great time talking about the process of enlightenment and how Christianity lost its way.

Mark Matousek: I was surprised to see you’d written a book about Jesus, considering your background in Zen Buddhism. How did that happen?

Adyashanti: It really was a labor of love. For the last two or three years, I’ve been doing one retreat a year that focuses on Jesus’s teachings, so this was a natural outgrowth of that.

MM: Why did you choose to emphasize the revolutionary Jesus?

A: That’s a characteristic of Jesus that speaks to me. When I was practicing Zen Buddhism intensively during my twenties, I went through this period of being involved with the Christian mystics. There was something I wasn’t finding in my Zen practice. Many years later I realized that what I was looking for was the opening of the spiritual heart. I got around to reading the New Testament and I didn’t even recognize the Jesus in those gospels. I literally thought, who is this guy? He came off as such a revolutionary. He was very outspoken about the issues of his day, the power structure of his own religion, political issues, and so on. In contrast to the typical Eastern sage removed from society, Jesus was very much a man of the world. We grow up with this idea of him as some sort of God-man transcendent of everything then you read the gospels and find out that he wasn’t at all. He had some very human characteristics.

MM: Is there a conflict for you between Christianity, which posits faith in God, and Buddhism that denies God’s existence?

A: From a theological perspective, there are obviously some very great differences. Personally, though, I don’t find a conflict because I look at these things from a big view and not through a tight theological lens. Both Jesus and Buddha are representations of archetypal spiritual patterns within us. The Buddha is the archetypal image of transcendent realization, that which was never touched by time and the world, nor by human difficulty. The Jesus story is an archetype of something quite different: an engaged realization. Jesus doesn’t find his freedom through transcendence of the world but from a very, very deep engagement. In the Jesus story itself, the spirit of heaven descends upon Jesus, which is a very different kind of spiritual awakening. It’s the descent of spirit into form rather than the arising spirit waking up out of form. Both of these are legitimate approaches to awakening. Our Western spiritual traditions, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, aim at achieving a relationship with the divine, whereas the Eastern, non-dual traditions aim at identification with (or as) the divine. At times, what’s missing from non-dual practice is the spiritual heart. You can have an extraordinary amount of transcendent realization without the spiritual heart, which is a deep, intuitive, intimate connectedness with life around you.

MM: In Resurrecting Jesus, you write, “the search for the historical Jesus isn’t the point. The point is the story, the collective dream.” What is to be gained by rediscovering the power of the collective dream?

A: In the West, when you call something a myth you are basically saying it’s not true. That’s a complete misunderstanding of what myth actually is, though. Myth is a story meant to convey something that can’t be put in ordinary language. So when we look at something like the Jesus story mythologically without worrying about how much is true, we can enter into a creative relationship with the story. Instead of asking what Jesus actually said, we can ask what this story evokes in us. Myths are meant to evoke hidden dimensions of human consciousness. The Jesus story becomes much more powerful in this way, as well as healing. We’ve grown up in a culture that’s absolutely dripping and saturated with this story. It has an immense influence on the Western psyche and if we can’t make real peace with that story, it becomes like a wound that doesn’t heal.

MM: The wound of Christianity?

A: The wound of how we’ve understood Christianity. I’ll give you an example. Part of the Judeo Christian tradition is the idea of Original Sin. As a result, you have this rampant disease of unworthiness in Western cultures that, for the better part of 2,500 years, have lived with this mythology of the fall. Until we can reinterpret this story, it’s very, very hard to heal the wound of feeling unworthy. We have to be able to go back and look at it again with fresh eyes. Jesus didn’t go around telling people that they were unworthy. It’s the theologians that went around after he died telling people they were unworthy. That never entered into any of Jesus’s dialogues at all.

MM: You write that Zen taught you about “the dimension of being far beyond personal psychology.” How would you describe this dimension?

A: There is a dimension of experience within you that’s eternal and has no history. It has no time, it has no past, it has no personality, it has no karma, it has no problem. It’s the dimension of consciousness that is literally outside of time and everything that touches time. The non-dual traditions, such as Zen, are very, very powerful at evoking that dimension of human experience. But this doesn’t necessarily solve problems relating to personal psychology. So you can be very deeply rooted in a very transcendent experience of being and still have some very problematic, unresolved issues in your psychology.

MM: As someone who lives in this dimension most of the time, do you struggle with emotions and conflict in daily life?

A: There hasn’t really been much struggle for the past ten years or so. Of course, it could be different when I get out of bed tomorrow. (laughs) The underlying feeling state for me is contentment. It’s a serene kind of joy that underlies everything. At first, I had a very powerful awakening to eternity and then, over the ensuing years, my spirituality moved toward embracing everything that I had transcended, the nature of human emotion, personality, and so on. What I’ve found is that the dimension of eternity and the dimension of time are really one in the same. I just feel at ease with it all. I’m at ease with my humanity. I’m at ease with eternity. I’m at ease with life. It doesn’t mean that everything goes smoothly. I’m like everybody else. Life has its challenges but it’s just not a big deal. There’s an underlying sense of ease and Ok-ness.

MM: What do you find most challenging?

A: To be quite honest, very trivial things. The thing I probably find most challenging in personal life is my computer. I’m not joking. The bigger things aren’t big challenges for me anymore. But I can get frustrated at my computer and the first thing you’ll hear is me yelling for my wife to come help me. Mukti, come and save me from this device! I found the devil and it’s a computer. Strangely enough, when humans don’t do the things you might expect them to do, that’s not really very frustrating to me. I totally get that.

MM: You don’t get angry at people?

A: No, not really. Years ago, I had this realization, this experience, where something just finally completely fell away. The whole self-structure, which is the thing that’s always looking within. The turn of consciousness that’s always evaluating things. The whole self-structure just sort of fell away. The most honest way I can describe it is that I lost my inner world. So when things happen, they just happen. There’s not much inner life for them to affect.

MM: There’s nothing to protect.

A: Right. There’s nothing to protect. There’s no inner story that feels compelled to protect itself.

MM: Finally, I’d like to ask you about the notion of divine incarnation, regarding Jesus, Buddha, or anyone else described as an avatar. How do you interpret that?

A: I think that every single incarnation is a divine incarnation. I know nothing nor do I care to know about avatars. I think “avatar” is an idea. And the idea is separative. It assumes that there are divine incarnations as opposed to what? Other people that aren’t divine? How can that possibly be? Because one person has realized it and another hasn’t? If somebody hasn’t discovered their true nature it doesn’t make them one iota less divine. Some people may come into their incarnation never having forgotten their true nature; if someone wants to call that person an avatar, fine. But when we think that avatars have some sort of “more essential divinity,” we’re back in the world of separation, duality, and mind-made divisions that aren’t really there. If someone is born in full remembrance of who they are, good for them.. But that doesn’t mean they have more divinity than a heroin addict in the gutter. The heroin addict doesn’t know that they’re divine —that’s the difference. It’s a relative difference, not an essential difference. And that’s what I love about the Jesus story. He got made into an avatar and the God-man and all this stuff after he died, but his way of moving in the world was very ordinary. He was a very outspoken critic of the various ways that us human beings create divisions and then take advantage of those divisions. That’s why I say that enlightenment doesn’t raise you, it actually lowers you because you see the reality of all beings. Not just your beings, but all beings. Otherwise it’s just an enlightened ego that thinks it’s better than, more spiritual, or whatever. It shows you that all ultimately on the same playing field. We’re the same stuff. In that absolute sense, we are all of profound equality. To me, the enlightened view is the ultimate form of democracy.