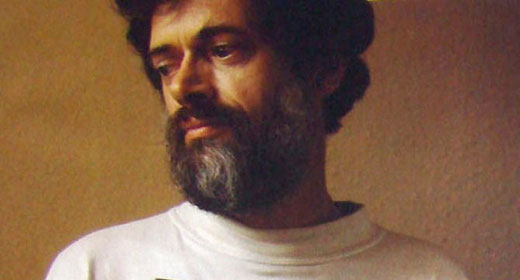

Stanislav Grof, M.D., Ph.D. is a psychiatrist with over fifty years’ experience researching nonordinary states of consciousness.  Dr. Grof and his wife Christina have recently written Holotropic Breathwork: A New Approach to Self-Exploration and Therapy, the culmination of their research, a justification of many of the techniques used in transpersonal therapy, and the capstone to a brilliant career.

Dr. Grof and his wife Christina have recently written Holotropic Breathwork: A New Approach to Self-Exploration and Therapy, the culmination of their research, a justification of many of the techniques used in transpersonal therapy, and the capstone to a brilliant career.

Holotropic Breathwork produces a natural psychedelic “high,” combining effective breathing with wonderfully evocative music to access the spontaneous healing potential of the individual. It allows access to deeper levels of the psyche, including personal biography, psychological death and rebirth, and the entire transpersonal spectrum.

Dr. Grof will be speaking at the San Francisco New Living Expo and also at East West Bookstore in Mountain View. For details about each of these venues please see OPEN EXCHANGE’s Conferences category.

The following is an excerpt from an unpublished conversation I had with Dr. Grof in 1992. I think you’ll find the topic as fresh as ever, and Dr. Grof’s reputation has only grown in the interim. Let us know if you enjoy this interview and want to read more like it. —Bart Brodsky

BART BRODSKY: Please describe your contribution as one of the originators of transpersonal psychology.

STANISLAV GROF: I have done a lot of work in the area of nonordinary consciousness, basically clinical research of psychedelics, both in the United States and then before, in Prague. Some of these were government sponsored clinical projects exploring therapeutic potential of psychedelic substances, and also what we can learn about the psyche. In this context I observed that people, in their experiences, were going off very, very far beyond the experiential framework that is defined by psychoanalysis and by mainstream psychology and psychiatry. The traditional framework is basically limited to biological aspects, in relation to the psychic [makeup] of the brain and then in terms of computer language, what we would call software, the programs that are there, basically limited to post-natal biography, to what happened to us in infancy, childhood, and later life. And then the unconscious part brought in individual unconscious.

BB: You make an interesting statement in The Holotropic Mind that there’s a tendency among traditional therapists to see nonordinary states as pathological. In the 60s [psychiatrist] R.D. Lang wrote that nonordinary states were not necessarily wrong or worse states of reality, but simply different. Was he an influence on your work in any way?

SG: No. I knew him. We met, we presented at conferences jointly, but those are mostly independent observations.

BB: In the Holotropic Mind you also talk about “consensus reality,” versus objective reality. Could you summarize briefly?

SG: Well, consensus reality is basically the way we agree the world is. Obviously, we all don’t see it exactly the same way, so there would be variations, but there’s sufficient overlap in individual perceptions of the world that we can talk about some kind of joined reality. But what’s very interesting is that when you study nonordinary states you’ll find out that there’s also consensus. But of course, you have to visit those different realms and talk about them with people who have had similar kinds of experiences. And then there is a significant agreement on what people have experienced in these realms, although they are not consensus reality in the ordinary sense.

BB: You have mapped nonordinary states in The Adventures of Self Discovery and The Holotropic Mind, perhaps, better than anybody else in the therapeutic movement. How is your work being met by other experts in the field?

SG: I don’t think it has penetrated sufficiently to the kind of mainstream academic circles, universities, research institutions, and so on. Mostly people in transpersonal psychology, humanistic psychology. We just had a twenty-fifth anniversary of transpersonal psychology and I got a special award for the contributions of the field together with Ken Wilber. That’s a major, major appreciation from those circles, but I would say within the academic circles those would be mostly individual rather than the academic as a whole. They still tend to see everything that transpersonal psychology describes as being in the realm of pathology. There is a significant category of experiences that people have when they move beyond the biographical framework, and those are the experiences that we call transpersonal. These are experiences of identification with animals, animal consciousness or connecting with other aspects of nature. They can have experiences of deities, demons, of different cultures. That’s what Carl Gustof Jung called “the collective unconscious.” They can have past life experiences, experiences with cosmic consciousness, and so on. My specific contribution was to map [these] and suggest that the psychic model should be extended to include all those other experiential realms.

BB: And in doing so you’ve greatly expanded the model for the psyche itself. I want to ask you about the dangers of getting lost along the way, in this incredible, wild ride of birth, death, and rebirth, eroticism and demons. Do your maps help keep people from getting lost, or is it the quality of the guide that is key during these experiences?

SG: I have gotten a lot of positive feedback from people who have had psychedelic experiences on their own, unsupervised you know, in the 60s, when there was all this wild experimentation, and still had some confusion about those experiences, and they felt that the contribution which I had put together sort of helped them to understand and integrate what had happened to them in those years. And also people who had spontaneous episodes of nonordinary states, something that we call a spiritual emergency.

BB: Do you think that Tim Leary and others who wanted to popularize LSD in the 60s may have been wrong in their, say, enthusiasm for the drug?

SG: I think the major problem was that the image of the experience was kind of one-sided. If you’re advertising something you don’t necessarily talk about the negative side of the phenomenon. And so, I think they were very accurately portraying the positive potential. You can have really ecstatic experiences, of course, with unity, tremendous expansion of consciousness, and that I think should be emphasized. But what wasn’t talked about is that we can also have a kind of hellish, disorganized experience, and there can be negative consequences to this.

BB: Is that, perhaps, why Huxley wanted to keep the drug for the “illuminati.”

SG: Yes, I think he believed that what has happened throughout ages that keeping these things within select circles somehow would safeguard against some of these complications.

BB: Was John Lilly any influence on your work?

SG: We have been friends for probably 27 years. But again, his work kind of went parallel to mine. He basically has done a lot of self-experimentation, taken an enormous amount of psychedelic substances, and written about it profusely. In my work, I’ve certainly had my share of it personally, but I’ve also worked with many, many hundreds of people in over 4,000 psychedelic sessions, which is a different kind of experience from John’s. John has done the work with the dolphins, and he’s done a lot of original experiments.

BB: Your own technique, Holotropic Breathing, is a non-drug technique. Is it safer than drugs because it’s more or less a natural technique? If so, can it be as intense?

SG: I think generally it’s much, much safer. Because with the psychedelic substances, once you’ve taken it, it’s too late to change your mind. There’s no safe way of really interrupting it. If you experience fear, you can take tranquilizers [which] can create a lot of problems after the session. So, the best thing you can really do is stay with it and hope that what your’re experiencing will be well resolved. Now, with [Holotropic] breathing, you see the situation is different because you have to continuously work for it. You can renegotiate whether or not you want to experience something, how far you want to go. So the experiences would not generally be so overwhelming. Now, to answer the other part of your question, how intense these experiences are depends on where people are. There are people who have very, very powerful experiences very close to the surface, sometimes to the point where it’s more difficult for them to hold them down. When people come to our workshops they can have extremely powerful experiences.

BB: Again, it sounds to me that the quality of the guide is very important in delving into these realms, because you can bring up such an intense experience.

SG: Whether you’re talking about psychedelics or Holotropic Breathwork, you’re talking about a tool. You have an approach that can somehow bring you in touch with deep levels of consciousness, and there’s nothing intrinsically healing about the therapy nor destructive. In other words, what’s going to happen depends very much upon what’s called “set and setting,” which means who’s doing it and under what circumstances, which means the quality of the rapport, the quality of the guide, the help with the situation, and so on, are all really critical.

BB: I’ve experienced what I would describe as cosmic unity or ecstasy doing something as simple and natural as backpacking. And I’ve also had it doing kundalini yoga, which is essentially rhythmic, controlled breathing. Is there something fundamentally different between these experiences and something which I might have doing Holotropic Breathwork?

SG: I don’t think it’s different, because even if you take something like LSD, ultimately to study it, it’s only a catalyst. In other words, when you take LSD you don’t have an “LSD experience,” you have an experience of yourself that was made possible by a catalytic affect. And the experience can be triggered in many different ways….