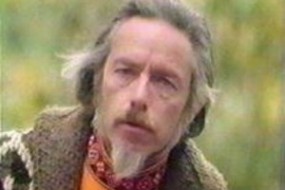

Alan Watts: On returning to America I was introduced to psychiatric adventures of a different order, for Aldous Huxley had recently published Doors of Perception  about his experiment with mescaline, and had by this time gone on to explore the mysteries of LSD. Gerald Heard had joined him in these investigations, and in my conversations with them I noticed a marked change of spiritual attitude. To put it briefly, they had ceased to be Manicheans [or simple and dualistic in their thinking about the nature of the Universe]. Their vision of the divine now included nature, and they had become more relaxed and humane, so that I found myself talking to men of my own persuasion.

about his experiment with mescaline, and had by this time gone on to explore the mysteries of LSD. Gerald Heard had joined him in these investigations, and in my conversations with them I noticed a marked change of spiritual attitude. To put it briefly, they had ceased to be Manicheans [or simple and dualistic in their thinking about the nature of the Universe]. Their vision of the divine now included nature, and they had become more relaxed and humane, so that I found myself talking to men of my own persuasion.

Yet it struck me as highly improbable that a true spiritual experience could follow from ingesting a particular chemical. Visions and ecstasies, yes. A taste of the mystical, like swimming with water wings, perhaps. And perhaps a reawakening for someone who had made the journey before, or an insight for a person well practiced in something like Yoga or Zen.

Nevertheless, on these “inner planes” I am of an adventurous nature, and am willing to give most things a try. Both Aldous and my former student at the Academy, mathematician John Whittelsey, were in touch with Keith Ditman, psychiatrist in charge of LSD research at the UCLA department of neuropsychiatry. John was working with him as statistician in a project designed both to test the effect of the drug on alcoholics and to make a map of its effects on the human organism.

So many of their subjects had reported states of consciousness that read like accounts of mystical experience that they were interested in trying it out on “experts” in the field, even though a mystic is never really expert in the same way as a neurologist or a philologist, for his work is not a cataloguing of objects. But I qualified as an expert insofar as I had also a considerable knowledge of the psychology and philosophy of religion: a knowledge that subsequently protected me from the more dangerous aspects of this adventure, giving me a compass and something of a map for this wild territory. Furthermore, I trusted Keith Ditman. He wasn’t scared, like so many Jungians, of the unconscious. Nor was he foolhardy, but seemed level-headed, cautious, tentative in opinion, yet lively, bright-eyed, and intensely interested in his work.

We made, then, an initial experiment at Keith’s office in Beverly Hills in which I was joined by Edwin Halsey, formerly private secretary to Ananda Coomaraswamy, and then teaching comparative religions at Claremont. We each took one hundred micrograms of d-lysergic acid diethylamide-25, courtesy of the Sandoz Company, and set out on an eight-hour exploration.

For me the journey was hilariously beautiful – as if I and all my perceptions had been transformed into a marvelous arabesque or multidimensional maze in which everything became transparent, translucent, and reverberant with double and triple meanings. Every detail of perception became vivid and important, even ums and ers and throat-clearing when someone read poetry, and time slowed down in such a way that people going about their business outside seemed demented in failing to see that the destination of life is this eternal moment.

We walked across the street to a white, Spanish-style church, surrounded with olive trees and gleaming in the sun against a sky of absolute, primordial blue, and saw the grass and the plants as inexplicably geometrized in every detail so as to suggest that nothing in nature was disordered. We went back and looked at a volume of Chinese and Japanese sumi, or black-ink paintings, all of which seemed to be perfectly accurate photographs. There were even highlights and shadows on Mu’ch’i’s persimmons that were certainly not intended by the artist. At one time Edwin felt somewhat overwhelmed and remarked, “I just can’t wait until I’m little old me again, sitting in a bar.”In the meantime he was looking like an incarnation of Apollo in a super-natural necktie, contemplatively holding an orange lily.

All in all my first experience was aesthetic rather than mystical, and then and there – which is, alas, rather characteristic of me – I made a tape for broadcast saying that I had looked into this phenomenon and found it most interesting, but hardly what I would call mystical. This tape was heard by two psychiatrists at the Langley-Porter Clinic in San Francisco, Sterling Bunnell and Michael Agron, who thought I should reconsider my views. After all, I had made only one experiment and there was something of an art to getting it really working.

It was thus that Bunnell set me off on a series of experiments which I have recorded in The Joyous Cosmology, and in the course of which I was reluctantly compelled to admit – at least in my own case – LSD had brought me into an undeniably mystical state of consciousness. But oddly, considering my absorption in Zen at the time, the flavor of these experiences was Hindu rather than Chinese. Somehow the atmosphere of Hindu mythology and imagery slid into them, suggesting at the same time that Hindu philosophy was a local form of a sort of undercover wisdom, inconceivably ancient, which everyone knows in the back of his mind but will not admit. This wisdom was simultaneously holy and disreputable, and therefore necessarily esoteric, and it came in the dress of a totally logical, obvious, and basic common sense.

In sum I would say that LSD, and such other psychedelic substances as mescaline, psilocybin, and hashish, confer polar vision; by which I mean that the basic pairs of opposites, the positive and the negative, are seen as the different poles of a single magnet or circuit. This knowledge is repressed in any culture that accentuates the positive, and is thus a strict taboo.

It carries Gestalt psychology, which insists on the mutual interdependence of figure and background, to its logical conclusion in every aspect of life and thought; so that the voluntary and the involuntary, knowing and the known, birth and decay, good and evil, outline and inline, self and other, solid and space, motion and rest, light and darkness, are seen as aspects of a single and completely perfect process. The implication of this may be that there is nothing in life to be gained or attained that is not already here and now, an implication thoroughly disturbing to any philosophy or culture which is seriously playing the game which I have called White Must Win.

Polar vision is thus undoubtedly dangerous – but so is electricity, so are knives, and so is language. When an immature person experiences the identity of the voluntary and the involuntary, he may feel, on the one hand, utterly powerless, or on the other, equal to the Hebrew-Christian God. If the former, he may panic from the sense that no one is in charge of things. If the latter, he may contract offensive megalomania. Nevertheless, he has had immediate experience of the fact that each one of us in an organism-environment field, of which the two aspects, individual and world, can be separated only for purposes of discussion. If such a person sees thus clearly the mutuality of good and evil, he may jump to the conclusion that ethical principles are so relative as to be without validity – which might be utterly demoralizing for any repressed adolescent. Fortunately for me, my God was not so much the Hebrew-Christian autocrat as the Chinese Tao, “which loves and nourishes all things, but does not lord it over them.”

I hesitated a long time before writing The Joyous Cosmology considering the dangers of letting the general public be further aware of this potent alchemy. But since Aldous had already let the cat out of the bag in Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell, and the subject was already under discussion both in psychiatric journals and in the public press, I decided that more needed to be said, mainly to soothe public alarm and to do what I could to forestall the disasters that would follow from legal repression. For I was seriously alarmed at the psychedelic equivalents of bathtub gin, and of the prospect of these chemicals, uncontrolled in dosage and content, being boot-legged for use in inappropriate settings without any competent supervision whatsoever.

I maintained that, for lack of any better solution, they should be restricted for psychiatric prescription. But the state and federal governments were as stupid as I had feared, and by passing unenforceable laws against LSD not only drove it underground but prevented proper research. Such laws are unenforceable because any competent chemist can manufacture LSD, or a close equivalent, and the substance can be disguised as anything from aspirin to blotting-paper. It has been painted on the thin pages of a small Bible, and eaten sheet by sheet. But as a result of this terror, the injudicious use of LSD (often mixed with strychnine or belladonna or quite dangerous psychedelics) has afflicted uncounted young people with paranoid, megalomaniac, and schizoid symptoms.

I see this disaster in the larger context of American prohibitionism, which has done more than anything else to corrupt the police and foster disrespect for the law, and which our economic pressure has, in the special problem of drug abuse, spread to the rest of the world. Although my views on this matter may be considered extreme, I feel that in any society where the powers of Church and State are separate, the State is without either right or wisdom in enforcing sumptuary laws against crimes which have no complaining victims.

When the police are asked to be armed clergymen enforcing ecclesiastical codes of morality, all the proscribed sins of the flesh, of lust and luxury, become – since we are legislating against human nature – exceedingly profitable ventures for criminal organizations which can pay both the police and the politicians to stay out of trouble. Those who cannot pay constitute about one-third of the population of our overcrowded and hopelessly mismanaged prisons, and the business of their trial by due process delays and overtaxes the courts beyond all reason. These are nomogenic crimes, caused by bad laws, just as iatrogenic diseases are caused by bad doctoring. The offenders seldom feel guilty but often positively righteous in their opposition to this legal hypocrisy, and so emerge from prison loathing and despising the social order more thanever.

I speak with passion on this problem because I have often served as a consultant to the staffs of state institutions for mental and moral deviants, such as the institutional hells which the State of California maintains at San Quentin, Vacaville, Atascadero, and Napa – to mention only those I have visited, and knowing that they are considerably worse in other parts of the country, and most especially in those states afflicted with religious fanaticism. Relative to our own times, the prosecution of sumptuary laws is as tyrannical as any of the excesses of the Holy Inquisition or the Star Chamber.

My retrospective attitude to LSD is that when one has received the message, one hangs up the phone. I think I have learned from it as much as I can, and, for my own sake, would not be sorry if I could never use it again. But it is not, I believe, generally known that very many of those who had constructive experiences with LSD, or other psychedelics, have turned from drugs to spiritual disciplines – abandoning their water-wings and learning to swim. Without the catalytic experience of the drug they might never have come to this point, and thus my feeling about psychedelic chemicals, as about most other drugs (despite the vague sense of the word), is that they should serve as medicine rather than diet.