by Lama Surya Das: Many people have been asking me of late if Steve Jobs really was a Buddhist. The answer is yes, and for many years.

He was a Zen Buddhist, which inspired his simple, informal, monkish black dress code and the meticulously minimalist yet elegant consumer products he so ingeniously designed. If you look at Vincent van Gogh’s self-portrait as a Zen monk you’ll find many similarities with that other famously difficult creative genius.

He was a Zen Buddhist, which inspired his simple, informal, monkish black dress code and the meticulously minimalist yet elegant consumer products he so ingeniously designed. If you look at Vincent van Gogh’s self-portrait as a Zen monk you’ll find many similarities with that other famously difficult creative genius.

Perhaps Steve was van Gogh’s tulku (reincarnation).

Like Jobs, van Gogh was also a religiously inclined lay preacher of sorts, full of mystic zeal, creative energy and egalitarian ideals — and an equally volatile spirit who didn’t play well with others. In 1888, van Gogh painted himself as a monk in “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Gauguin.” He describes how he painted it “as the portrait of a Bonze, humbly worshipping the eternal Buddha and made the eyes slant slightly, after the manner of the Japanese.” Some scholars think the painting was meant as an intense affirmation of an ideal: to be the “calm monk” who can discipline and control the “mad painter.” (At the time, van Gogh was imagining founding a community of artists. In representing himself as a bonze [Buddhist monk], he painted himself as an inhabitant of his ideal community.) All these components also informed Jobs’ spiritual search, career path, proselytizing and the new silicon community he helped initiate. In his letters, Theo van Gogh said of his brother Vincent: “It is as if he had two persons in him — one marvelously gifted, delicate and tender, the other egotistical and hard hearted. … It is a pity that he is his own enemy.”

Sound familiar?

Jobs was a late product of the 1960s, who openly admitted that his psychedelic experiences had greatly informed his creative thinking. He’d actually dropped out of hip Reed College in Oregon after one semester, hung out at the Berkeley and Stanford campuses, and tripped around chaotic, cacophonous India for half a year or so as a truth-seeker, meditating and inquiring intently into mystical matters. After returning to the South Bay area in 1975, over the years he sat in Zen meditation retreats at sylvan Tassajara Zen Center near Big Sur and was good friends with some of my hippie vagabond friends, who had also spent time in India.

Some wonder exactly what kind of Buddhist could be so famously impatient, rude and demanding. How could he be so emotional, even throwing tantrums? Relentlessly stubborn, he could be brutal to close friends, family and colleagues, act ruthlessly in both business and personal affairs and claim credit for others’ ideas. Speaking as a fellow Buddhist, albeit of a different lineage, I have no easy answer or apology to offer for him in this respect. I think his having been adopted played into it — the master of design simplicity had some very messy elements of his personal life. We teach what we need to learn, as the saying goes.

Maybe that’s why this very complex and even contradictory personality so assiduously sought and loved simplicity.

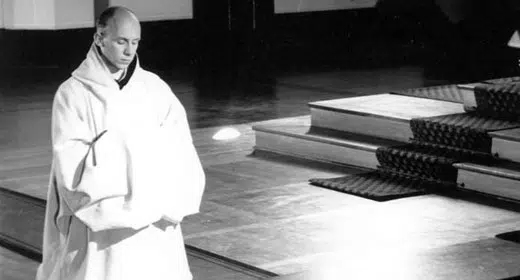

As it happened, he became a Zen Buddhist and followed for two decades a Japanese master living in Santa Cruz, Kobun Chino Roshi, and a married Zen monk. Roshi seems to have had an influence on Jobs in one notable respect — as a spiritual leader more interested in the great Zero (of sunyata, the void), than in oneness and other larger, more collective numbers. Kobun seemed focusessed too much on cold and clear emptiness, not enough on warm and empathic compassion, attitude-transforming loving-kindness practice. Too much head and not enough heart, a common critique of some Zen Buddhist lineages.

It was no accident that Kobun Sensei, as his students call him, attracted Steve Jobs. Kobun was buddies with the provocative and controversial master Tibetan lama Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, the pioneering founder of the Naropa Institute in Boulder, a valuable teacher to many of us in the 1970s. Jobs could be more of a ronin — masterless samurai — than a saintly sattvic spiritual seeker. In fact, he was the personification of, as one oft-misunderstood Zen saying puts it: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.” (Which cautions against believing in any such thing as Buddha, or anything substantial, outside. It has nothing to do with life taking.) Consider the grandiose tone of Jobs’ in-your-face challenge to then Pepsi-Cola chief John Sculley: “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water, or do you want a chance to save the world?”

There was method in Jobs’ madness, as Sculley became the head of Apple and the highest paid executive in Silicon Valley.

I don’t use Apple products (for no real reason, other than I got started with DOS) and hadn’t seen Jobs in years when he died, but I did get to know him a bit while staying in his home for a couple of days in 1978. He had just opened his original one-story Cupertino factory, living alone in an empty suburban house with little or no furniture. His bedroom had a double mattress on the floor and two huge stereo speakers, one on either side, and little else. (Steve thought couches were superfluous.) My friend and I slept and sat to meditate on the carpeted floor in another bedroom even barer than Steve’s. I think we ate cold cereal for breakfast and broccoli for dinner, more than once. There was a phone with a cord attached to the kitchen wall. (I could see he was obviously handy, knew carpentry and learned a little Japanese calligraphy — all early influences on his engineering style.)

At the time, Steve was working intensely, as usual, on some kind of new electronics, which was news, as well as Greek, to me. (It was both new and geek to everyone, we’d eventually discover.) Steve said that sitting in meditation helped him focus as well as gain an uber-view of his own inner mind, effects I could certainly relate to. And he wondered how to use this in his work, electronically. It was obvious that he was working very hard, obsessing about his new project day and night.

He also paid a psychedelic relic friend, clad in flowing handmade Indian cotton garb, to walk around the half-empty factory floor and strum his Indian instruments, singing mellifluous kirtan, hymns of divine praise we’d all learned at ashrams in India. He told us Jobs had hired him “to upgrade the group consciousness.” I remember wondering at the time how serious and high-minded Steve actually was, given the electrical engineering shop environment and his alpha-male tendencies and ambitions. To his credit, Steve did help the following year with some much-needed seed-money — a $5,000 donation with no strings attached — for some of us to create in 1979 the SEVA Foundation, (a charity working in developing nations), which is still going strong. I’m grateful to him for that.

So he wasn’t especially generous, humble or kind. Then perhaps the virtuous aspect of the Noble Eight-fold Path taught by Buddha that Steve Jobs did exemplify was Step Five, Right Livelihood and True Vocation, one of the most interesting, challenging and relevant aspects of our life’s journey. How to align our work and our life, our personal and professional lives with (and inseparable from) our home, love and inner spiritual lives? Is this not one of our greatest challenges? Jobs seemed to skillfully blend his occupation and talents into his creative true calling — working wholeheartedly at the intersection of the humanities and the science, as he once said.

Jobs often said he wanted to make something beautiful and not just new, useful or successful. The inner level of Right or Wise Livelihood is doing what needs to be done, something we all aspire to but are often insufficiently aware of or able to achieve. I believe that making this world and life a better and more beautiful place for all is our true work and vocation.

Fairly, some might dispute that Steve’s business ethics and tactics accorded with the principles of Right Livelihood, or even that the compassionate life of the altruistic Enlightened Leader could ever possibly combine running a grand entrepreneurial business with the even greater work of edifying and enlightening the world. I personally would love to hear this further discussed and explored for the benefit of upcoming generations. Suzuki Roshi of San Francisco Zen Center used to say: “You’re perfect just as you are — and still you could use a little improvement.” This is fine wine, heady stuff. How to get from here to truly and totally here is the modern conundrum, beyond linear ideas of progress, where mindful awareness proves indispensable.

Now everyone is talking about and even apotheosizing Steve, which is, like most public discussion, both more and less than the whole story. Seasoned journalist Walter Isaacson’s big new biography of him is an excellent read, and full of stories and historical record (although Isaacson remains tone-deaf to things foreign to him, such as Zen Buddhism’s cryptic teaching and ancient Asian-style chanting and rituals), including those at Jobs’ 1991 Yosemite wedding to Laurene Powell, where his Zen priest-teacher Kobun officiated.

In his 20s, Steve predicted he would die before the age of 40, although no one seems to have known why. What affected me most about his untimely death was how young he was, only 56.

How rarely does such a brilliant shooting star pass through this local universe where people like us live, breathe, walk, wonder, work and play.