We hear a lot about “joy to the world” this time of year. This morning, our Seth Doane introduces us to a man for whom joy is just part of the job.

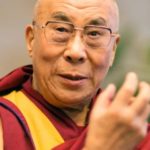

The 14th Dalai Lama is the world’s most celebrated monk: a Nobel Peace Prize-winner, and the spiritual leader of six million Tibetan Buddhists … a man with a message of compassion and non-violence so meaningful, and so cool, he’s been featured in Apple ad.

So though we’d arranged to meet him, it still seemed a bit-other-wordly to see the Dalai Lama emerge from a hotel elevator.

He’s known to avoid formality, and did. The 81-year-old immediately accepted a little support from his interviewer.

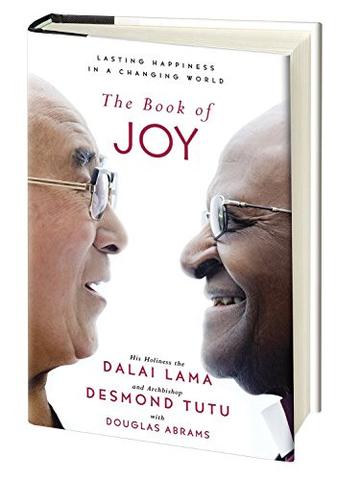

We met in Poland, where his busy schedule would allow, to discuss “The Book of Joy” (Avery). It’s based on a series of conversations he had with an equally-celebrated friend: South Africa’s retired Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a pillar of his nation’s struggle against apartheid.

The book they wrote with editor Douglas Abrams explores a topic appropriate to the season: How to live a more joyous life. It’s one of a hundred or so books the Dalai Lama has authored or lent his name to.

The book they wrote with editor Douglas Abrams explores a topic appropriate to the season: How to live a more joyous life. It’s one of a hundred or so books the Dalai Lama has authored or lent his name to.

Doane asked, “Why did you want to do a book about joy?”

“The subject is very good,” the Dalai Lama replied. “If some book about sort of anger, about war, I don’t want it.”

“But joy, you know something about.”

“Joy, yes! Happy! Not only just on the physical level, but mentally! Peace. Compassion. That’s the real joy.”

The Dalai Lama brings to the topic the perspective and purity of a monk. He does not smoke or drink. He’s taken a vow of celibacy. Doane asked, “Is there a lesson for the rest of us in that?”

“No, I don’t think,” he replied. “Every human being cannot be monk. And if human being becomes celibate, then humanity will cease, so better to have more reproduction.”

His message is simple: Most people look for joy in the wrong places. “Everybody seeks happiness, joyfulness, but from outside — from money, from power, from big car, from big house. Ultimate source of happy life, even physical health, [is] inside, not outside.”

It’s an inner peace which he taught himself to find. He says he does not get angry.

“Something must annoy you,” Doane said.

“A little bit, [but] very temporary, short. Some sort of reaction. Otherwise, no ill feeling. Through training, I think last 50, 60 years training, analytical meditation.”

He gets up at three o’clock every morning, and will mediate for four or five hours, wherever he is — a temple, a hotel room, a car.

“Now today, I take about one-hour drive, so in car, occasionally just looking, seeing here or there. In big field I saw some deer. Very nice.”

“What did you like about it?”

“Peaceful! Vegetarian. Peaceful. Very nice.”

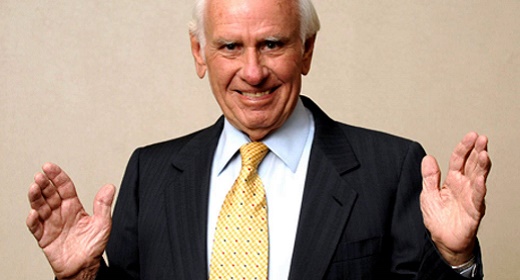

The Dalai Lama with correspondent Seth Doane.

He’s a man who seeks peace, but for most of his life has known conflict with adversary China, which bars him from returning to his native Tibet.

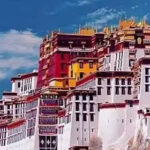

At just two years old he was identified as the reincarnation of the recently-deceased Dalai Lama, the name for the highest religious figure in Tibetan Buddhism. At age four he was brought to Tibet’s capital city, Lhasa.

It’s a story ripe for Hollywood, and it’s been dramatized by no less than director Martin Scorsese in “Kundun.”

He was just 15 years old when he became Tibet’s sole political and spiritual leader. That was in 1950 — the same year officially atheist Communist China occupied Tibet.

The Dalai Lama tried in vain to negotiate self-rule for his people. But in 1959 the Dalai Lama fled to India, following the Tibetan revolt against the Chinese. He formed a government in exile.

“We decided we are not seeking independence,” he told Doane. “We are not seeking separation. We are very much willing [to] remain within the People’s Republic of China.”

To this day, China views the Dalai Lama as an enemy of the state, and seeks to block him from traveling to certain countries or meeting heads of state.

The Dalai Lama said it doesn’t bother him.

Doane asked, “You must get a little agitated when a foreign leader won’t meet with you because of China.”

“No,” he replied. “My main purpose is promotion of human value, or promotion of religious harmony.”

He finds harmony through humor.

For the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu, joy and laughter go hand-in-hand.

Archbishop Tutu, laughing: “He’s not listening!”

Dalai Lama: “Unless, you use the stick, I will not listen!”

Archbishop Tutu: “But I thought you were non-violent!”

Their playful teasing runs throughout the hours of conversations from their work on the book.

Doane asked, “How important is humor for you?”

“Oh, important. Whether God creates, or by nature, we have the ability to smile. But I think a genuine smile really brings closeness.”

“A smile can bring people together?”

“Yes.”

As the Dalai Lama sees it, something as simple as a smile can change the world. And in a world marred by violence and rising nationalism, he says we must try to find commonality.

“Too much sort of nationalism: ‘We, we, we, we, we.’ And then? The problem, including violence, war.”

“You think to solve the world’s problems, we need to think beyond that which divides us? Beyond religion, beyond national boundaries?”

“Yes, I feel!”

And that from a spiritual leader. After the interview we asked for a picture with the crew. He asked us to join hands, and said finding solidarity, peace and joy starts with engaging those right beside us.