by K.M. Kostyal: Patient, modest, and deliberate: George Washington gave the United States the steady hand necessary to guide it through a revolutionary birth and its tumultuous early years…

“First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” That famous description of George Washington by his friend and fellow patriot Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee is probably still the best summation of the man who, over a hard but resolute lifetime, became the savior of a war and the father of a country. Washington’s earliest ambitions, though, aimed more at the prosaic than the glorious. He probably imagined nothing better than following in the footsteps of his father, Augustine, who had been an ambitious Virginia planter and merchant. Augustine was hardly a major player in the hierarchical world of the aristocracy, but he was nonetheless a bona fide member of the gentry. George was the eldest son of Augustine’s second wife, Mary, who was not, and at no point aspired to be gentry.

When George was just 11, Augustine died, leaving his younger children in the hands of Mary, a domineering, pious, possibly pipe-smoking woman who ran her farm with a firm hand and read daily to her children from Contemplations Moral and Divine. Though George’s two older stepbrothers, then grown, had been sent to the fine schools required of the Virginia gentry, George had no resources for that, and Mary, in any case, had no interest in investing in her eldest son’s education. Indeed the two clashed their entire lives, and some biographers speculate that George modeled himself after everything that his mother was not.

DEVOTED TO THE NATION

Feb. 22, 1732 George Washington is born in a modest house at Popes Creek, Westmoreland County, Virginia. His father, Augustine, is a plantation owner who dies when George is 11.

June 15, 1775 Having served with distinction in the French and Indian War, Washington is appointed as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army that was created the day before.

Dec. 23, 1783 Washington resigns his commission as commander-in-chief, having transformed the Continental Army into an effective fighting force and led the troops to victory over the British.

Apr. 30, 1789 Despite not actively seeking the candidacy, Washington is unanimously elected as the first president of the United States under the Constitution. He serves two terms but refuses a third.

Dec. 14, 1799 Washington dies suddenly after contracting an acute infection while touring his estates in the winter. The nation goes into mourning. Foreign governments, including Britain, pay homage.

Apparently determined to better himself from a young age, George found mentors among the gentry and emulated their ways. He also copied by hand the Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation. These 110 rules had been conceived by French Jesuits as a teaching tool almost a century and a half before, dealing with everything from table manners to posture to facial expressions to gossip. Despite their stuffy formality, George seems to have internalized them because they echoed through his behavior for the rest of his life. As a young man, George impressed the colonial power-brokers of British Virginia, who made him a surveyor of western lands and an officer with the British during the French and Indian War. He first saw battle in his very early twenties, and he learned that he liked it. As far away as Britain, the young colonel’s calm and courage under fire was appreciated, with a London gazette running a line from one of his letters: “I have heard the bullets whistle; and believe me, there is something charming in the sound.”

MOUNT VERNON

But Washington had also experienced other aspects of war—the meddling of politicians and the disdain of the British for the American officers. By 1758 he was tired of it all. Resigning his commission, he enthusiastically took up the life of a Virginia planter.

Washington had been renting a family farm in Northern Virginia from the widow of his older half-brother Lawrence, who died in 1752. Following the death of his sister-in-law, Washington officially inherited Mount Vernon in 1761. Situated on the broad Potomac, Mount Vernon was one of the great loves of Washington’s life.

As he began ambitious improvements to the plantation, he became involved with a wealthy young widow, Martha Dandridge Custis. The two were soon married. Washington had been infatuated before, but Martha proved a perfect life partner and comfort to the reserved, driven, and often overburdened Washington.

Along with the wealth and social standing that Martha brought to the marriage, she also came with two young children, who Washington cherished as his own. He settled easily into the life of a respected planter and enjoyed days spent with his family, improving the farm, fishing, hunting (particularly fox hunting), riding, feasting, dancing, and generally reveling in the style of the Virginia aristocracy. He no doubt assumed he would end his days at Mount Vernon as a British citizen.

THE COMING REVOLUTION

That, of course, was not to be. Like his fellow Virginians in the House of Burgesses, Washington became increasingly disillusioned with George III and his colonial minions. At this time British America was composed of 13 disparate colonies ruled by 13 legislatures, each committed to its own culture, economy, and often religion.“Fire and water are not more heterogeneous than the different colonies of North America,” one British traveler had pronounced. Together, they were home to a million and a half people, the population doubling roughly every 20 years. They were Britons at heart, but of many varieties: long-established colonial families, recent immigrants, and indentured servants. Enslaved African-Americans lived throughout the colonies with large concentrations in the Chesapeake region and the South, where an aristocracy evolved because of their labor. Washington frankly aspired to become part of the elite and had speculated on wild land to the west. He saw his investment fade with the royal Proclamation of 1763, which banned westward migration in an attempt to fend off more Indian wars and control the cost of America to the Crown.

BRITISH WAR DEBT

Washington fought in the French and Indian war which was part of the larger Seven Years’ War that raged across Europe from 1756-1763. Britain emerged from it with an empire greater than any the West had known since Rome. Its holdings in the New World, shown above, had more than doubled, but managing them proved an expensive business. To try and cover the costs, the British began to levy a series of taxes on the colonists that only added to the distress caused by a post-war bust in the economy. As the decade progressed, the loyal Britons of America, Washington among them, began to question their commitment to the motherland.

Yet through the 1760s, as he supported protests against British taxes, Washington also dined with the royal governor and assumed, as did most of his landed countrymen, that the British would be reasonable. By 1774 he had changed his mind.“The measures which [the British] administration hath for sometime been, and now are, most violently pursuing are repugnant to every principle of natural justice,” he wrote to a friend. In the course of a decade, Washington had become a full-throated patriot and one of Virginia’s seven elected delegates to the First Continental Congress. In August 1774, he left Mount Vernon for Philadelphia with fellow delegates Patrick Henry and Edmund Pendleton. Martha saw them off. “I hope you will stand firm,” she told Henry and Pendleton, adding, “I know George will.”

The six-foot-two-inch Washington had a way of affecting other men simply by his bearing, and the other delegates to Congress were duly impressed, seeing in him the reassuring promise of a true military commander. And that was clearly what Washington wanted them to see. He was not a fiery or inspired speaker nor was he an intellect, but he was confident that he could command men.

He got his chance a year later, when the Second Continental Congress appointed him commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. John Adams championed him for the position, and Abigail Adams described him in this way: “Dignity with ease and complacency—the gentleman and soldier look agreeably blended in him. Modesty marks every line and feature of his face.”

PEN INSPIRES THE SWORD

Thomas Paine was an admirer of Washington and spent the desperate autumn of 1776 as an aide-de-camp in the field. Though brave, Paine was no soldier. But his brief time with the army and Washington no doubt inspired him as he wrote the opening to his American Crisis—“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country.” In late December 1776, with the revolution on the verge of collapse, enlistments about to expire, and “summer soldiers” waiting to depart, Washington ordered Paine’s essay read to his men. Two days later, their surprise attack on Trenton, New Jersey, revived the American taste for war and the commitment to fight on.

Certainly, Washington exuded modesty when he addressed Congress with what sounded like a protestation at his appointment, “I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room, that I this day declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.” He may have been overwhelmed by the appointment, but he had also wanted it. And now, for better or worse, he had it.

WASHINGTON AT WAR

In early July he arrived in Cambridge to meet his “army,” finding an obstreperous, disorganized gaggle of New England militiamen, most hardscrabble farmers and small-time merchants, holding the British army at bay in Boston. Washington was determined to impose the discipline of a true army on these “exceedingly dirty and nasty people.” He also sought to protect them from themselves, putting in place hygiene practices to ward against the diseases that plagued military camps. Despite his initial private disdain, he moved tirelessly and confidently among them, understanding, even if they did not, how precarious the American military was.

If that summer tested Washington, it was only a small taste of what was to come. By 1776 he and his men were in a struggle for survival, yielding battle after battle to the British in New York. By year’s end, Washington had lost more than half of what had been, at best, an army cobbled together. Congress had essentially turned its back on him, and his closest confidantes and officers had intrigued against him, complaining of his inability to lead.

In fact, he had been indecisive and overly deferential, and now his army was in danger of collapse, as enlistment periods ended and desertion grew. “No man, I believe, ever had a greater choice of difficulties and less means to extricate himself from them,” he wrote to his brother Jack in late autumn. Yet, in spite of his own despondency, Washington rallied, understanding that if he did not turn the tide somehow, the Revolution would be a short-lived disaster. And so on a bitter cold Christmas night, Washington famously led his broken, barefoot army from their winter camp at Valley Forge, crossing the Delaware River to attack Trenton, New Jersey. The American victory there was small but profound, reinvigorating Washington, his forces, and the patriotic cause—at least for a few months.

For the next four years, Washington battled on, carping at Congress to feed and supply his men, fending off attacks on his own leadership, and all the while keeping an eye firmly on the enemy. Gradually, he learned to fight the British more strategically, using local militia to harass them and avoiding “a general action” that would “put anything at Risque [sic].”

His men came to revere him for his courage, calm, determination, and, above all, for being at their side battle after battle, march after march, year after grueling year. The Philadelphia patriot Benjamin Rush once declared that Washington had “so much martial dignity in his deportment that you would distinguish him to be a general and a soldier from among 10,000 people. There is not a king in Europe that would not look like a valet de chambre by his side.”

PEACE AT LAST

By 1781 Washington’s resolve had triumphed over the British, and two years later America could officially claim her hard-won independence. By then Washington was more icon than man to most of the world. One Dutch merchant who caught sight of him as he rode through Philadelphia with a contingent of light cavalry, wrote to his wife, “I saw the greatest man who has ever appeared on the surface of this earth… I don’t know if, in our delight at seeing the hero, we were more surprised by his simple but grand air or by the kindness of the greatest and best of heroes.”

But the war had taken its toll. At 51 Washington was no longer the vigorous athletic man he had been. He wore crude, ill-fitting dentures of human teeth and ivory that hooked onto his one remaining tooth and made his gums ache. His great consolation was that he could at last settle down at Mount Vernon with his family and live out his days with his “mind… unbent,” gliding “down the stream of life till I come to that abyss from whence no traveler is permitted to return.”

And for just a few years Washington was indeed allowed the life of an unbent mind, reveling in his daily routine as a planter, coming up with strategies to improve the operations and production of Mount Vernon and his other nearby farms, neglected over the nine years of his absence. He and Martha also entertained an endless stream of visitors, many of them strangers who came to pay homage to America’s hero.

WASHINGTON AND THE CONSTITUTION

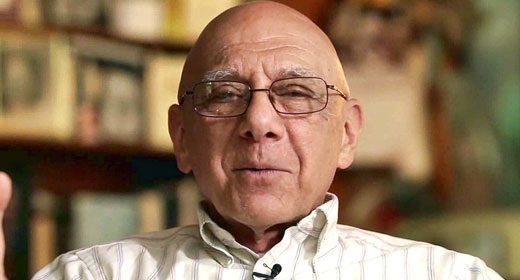

Having led the colonies to independence, Washington found himself again on the battlefront as the new nation began to form itself. It became obvious in the post-war years that the Articles of Confederation were no more than a toothless agreement between the states as conflicts erupted over trade, territory, waterways, and mutual protection. Washington tried to resolve one such dispute himself—over navigation rights to the Potomac. His talks, held at Mount Vernon in 1785, were a success and encouraged further cooperation among states. Four years later, Washington became the steadfast anchor around which endless arguments swirled about the nature and need for a new constitution (above). Though a Federalist with an eye to industry and infrastructure for a united country, Washington sat sphinxlike during the Philadelphia talks. These resulted in a constitution and a new role for Washington—not king, but president of the still fractious and embryonic United States.

RETURN TO THE LIMELIGHT

But Washington’s destiny was entwined with the new nation’s too completely to allow him escape. He watched its growing pains with the cautious eye of a concerned parent and, at the same time, he unobtrusively tended his own image, guarding it for posterity and holding himself in abeyance, in case he should be needed again. By 1787 he was back on the public stage and again on his way to Philadelphia, as he had been 40 years before, this time as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. He was quickly elected its president and within two years president of the new nation. He expected “that at a convenient and an early period my services might be dispensed with and that I might be permitted once more to retire.” But the “early period” dragged into eight years, as the former patriots argued and debated among themselves over America’s character and future.

Finally, in 1796, Washington refused to continue into a third term. This granted him barely three years of his own happiness at Mount Vernon. In mid-December 1799, after spending a cold, wet day touring his farms on horseback, he began to suffer a sore throat but he kept to his routines. Two days later he was gone. In his farewell address to the nation, he had assured his fellow citizens that “I shall carry… with me to my grave… unceasing vows that heaven may continue to you the choicest tokens of its beneficence; that your union and brotherly affection may be perpetual; that the free Constitution, which is the work of your hands, may be sacredly maintained; that its administration in every department may be stamped with wisdom and virtue; that, in fine, the happiness of the people of these States, under the auspices of liberty, may be made complete.”