How does a husband, a father, a pastor – a person responsible for the well-being of so many others – tread the path of his own spiritual awakening?

Princeton Theological Seminary graduate Paul Rademacher took on such a journey. In his autobiography, A Spiritual Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Universe, Travel Tips for the Spiritually Perplexed, he shares his personal adventures colored by a life-long passion to understand life beyond the confines of traditional thought. With gentle yet lucid insight, he exposes the distinctions between religion and spirituality, and provides some light along the way for those on similar paths.

Today he is the Executive Director of The Monroe Institute, a beautiful, rural facility that provides experiential education programs facilitating the personal exploration of human consciousness. SuperConsciousness recently spoke with Rademacher about the inner conflicts he confronted to be able to evolve and be where he is today, the inspirations that keep him longing for more, and the personal truth he has gained from his own experiences about the nature of the spiritual journey.

SC: In your experience, how do the unconscious yet deeply personal things that we keep hidden from ourselves interfere with the full realization of our spiritual self?

PR: Ultimately, spirituality is about wholeness. I love the story that Joseph Campbell tells about those who have gone on a journey and then they come back and tell others about it – people who think they are whole – but are really only fractions because so much of them remains hidden like an iceberg in that there is only a small percentage of awareness of themselves that is visible.

Yet we all sense an incredible essence about ourselves. Until we are able to move beyond our ordinary consciousness, we operate in this world as fractions and are unable to figure out what is wrong.

Spirituality, at one level, is about intentionally trying to reconnect with those parts of ourselves that we have pushed off. That is a very, very difficult journey to take because we spend so much time and energy to make sure the rest of the iceberg remains hidden. We are terrified of what is hidden, so it takes a lot of courage to begin to explore it. Yet, when we do, it’s like recovering lost energy of some sort – all the energy has been used to keep it hidden and keep it away from consciousness. When we become willing to open up to it, it is as if that energy gets recovered to some extent and you can use that energy for further exploration.

When it comes down to the practices, I think for a lot of people there is a tremendous hunger for the heretical. It is almost like a dam that has been stopped up for so long and just wants to burst out with this new energy.

SC: Can you give an example from your life?

PR: Probably one of the major things for most clergy is the whole issue of sexuality. The church has a push/pull around it, and if you are a pastor, it is aggravated all the more because the expectation somehow is that the pastor is supposed to be asexual.

SC: And still have a family?

PR: The implication of course is that all of our children are adopted. Or, if I have three children then that means I have only had sex three times in my life. For me, much of that came out of learning to suppress the sexual aspect of myself from a very early age. Sexuality was simply something that was not talked about, it was not displayed, and it was not even acknowledged as part of the human condition. So what better career for me to go into than the ministry where that [denial] was very much the expectation a congregation generally wants and expects.

The journey through the ministry and out of the ministry was this constant struggle of public persona versus passionate pursuit. The passionate pursuit was always about spirituality, moving beyond the confines of traditional thought – a passion that has never let go of me.

SC: You wrote about your frequent retreats while still in the ministry to a seminary in Detroit where you would gather with others and explore spirituality outside the more contemporary confines of Christianity. How important were those heretical pursuits for you while still in service as a pastor?

PR: It was life giving. Yet, at the same time, there was a real battle that went on in my head and still continues because there is this consensus of what is appropriate and what is heretical – but only in theory. When it comes down to the practices, I think for a lot of people there is a tremendous hunger for the heretical. It is almost like a dam that has been stopped up for so long and just wants to burst out with this new energy.

In my head there was this worry of losing my job and a concern about if I colored too far outside the lines that maybe people wouldn’t like me or they wouldn’t appreciate who I was. I backed off from actually testing that theory. Again, it was a question of courage.

I wish I could say I was a courageous person, but I don’t think I really am. I have had flashes from time to time, but when it comes right down to it, I’m like a lot of people and want to preserve my skin. I think because I didn’t take the risks that I should have or maybe that I could have, I don’t think I was able to fashion my career in ministry in a way that was life giving to me. I first had to go to other places like the [Detroit] theological center where I could begin to touch on some of this stuff for myself.

I recently conducted a Monroe Institute program for a Presbyterian group down in Florida. This group’s average age was 78 or 80. You would think that they would be a real closed group, but they just opened up to this material like crazy.

SC: Knowing deep inside some of the members of your congregation possessed that same hunger, did you find a way to initiate a conversation, help them to open the door, and start to talk about it?

PR: I did start a conversation with a small group within the church and they took to it like ducks to water. It was truly life giving for them also. But I didn’t know how to introduce that to the larger congregation. With any church, you have people who are all over the map in terms of the theological perspective, and as a pastor, you have to find ways to connect with all of the different constituencies. I just didn’t know yet how to begin to introduce those ideas to a wider audience. It tore at me. It kept me awake at night.

But, I will eventually find a way to do that. I recently conducted a Monroe Institute program for a Presbyterian group down in Florida. This group’s average age was 78 or 80. You would think that they would be a real closed group, but they just opened up to this material like crazy. I know that there is an audience there, but I’m still struggling on how to get it.

SC: You now helm an institute that helps people create experiences that are out of the normal day-to-day flow of material life. What do people begin to understand through the Monroe training?

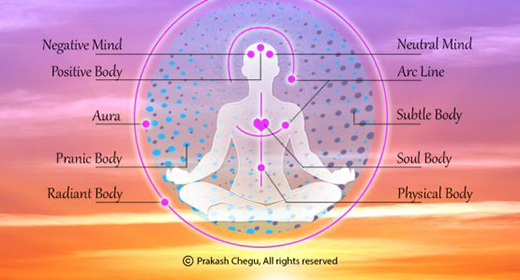

PR: The dichotomy between the spiritual and the material world is false; there is no difference between those. The physical world is infused entirely with the spiritual world. Once we start down that journey of pursuing awareness, not just in the physical work, but also in the metaphysical, then we open up to both realms. It isn’t a choice of either: It’s a question of both.

The full life is about trying to the best of our ability, Lord knows we fail at it continually, to reconnect, understand and open up to this spiritual domain that is infused into this life in every step of the way. Because of that, this life has a value and purpose that I think is not widely recognized because so many people are sick of this world or they want to find some kind of spiritual path that will take them out of this world, like this life is going to be my last reincarnation. I think there is a real mistake in this. I believe we have come here for a reason, and that reason has infinite value.

SC: There tends to be a misunderstanding about out-of-body work that reinforces the material/ spiritual dichotomy, yet it seems to bring spiritual validity to our perceived material world, we have to come to the understanding that spirituality includes the body, not separate from the body. As long as we perceive it separately, we are stuck. Yet, you encourage that people re-infuse the physical body with their spiritual experiences to help develop that unity, that sense of wholeness.

PR: It is an interesting dichotomy. On the one hand the Institute has been known for the out-of-body exploration, but that has been a misnomer. That is something we struggle with all the time as we try to reshape the public perception of what we do since most of that point of view comes from just reading Bob Monroe’s books which were all about the out-of-body experience.

There tends to be a misunderstanding about out-of-body work that reinforces the material/spiritual dichotomy, yet it seems that to bring spiritual validity to our perceived material world, we have to come to the understanding that spirituality is through the body, not separate from the body.

In truth, Bob Monroe and the Institute over the years have found out that this is just one small slice of a very, very big pie. There is a renewed emphasis on bringing together the physical experience and the metaphysical experience into a whole. We really see ourselves as being of service to humanity and continue to look in the best way possible to help promote some kind of global awakening. That is really the force that drives us to do what we do.