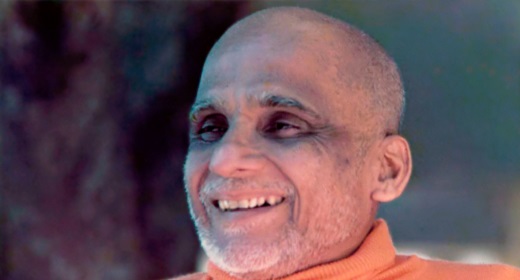

by Oliver Burkeman: Eckhart Tolle, Oprah Winfrey’s favourite guru, has sold more books than almost any other spiritual author. So what’s his Easter message?

When Eckhart Tolle was 29, he says, he underwent a cataclysmic and terrifying spiritual experience that erased his former identity. One evening, he was a near-suicidal graduate student, living in a Belsize Park bedsit; by the following morning, he’d been flooded with a sense of “uninterrupted deep peace and bliss” that has never left him since. That morning, he writes, “I walked around the city in utter amazement at the miracle of life on earth, as if I had just been born.” Tolle says he doesn’t mind the fact that some sceptics don’t believe this story, though the sceptics might reply that he doesn’t have much choice: once you’ve told the world that you abide in a realm of infinite equanimity, you can’t very well start getting all snippy when people don’t take you at your word.

The books that grew out of his Belsize Park epiphany, The Power of Now and A New Earth, have made Tolle by some measures the most successful spiritual author of the modern age, with tens of millions of copies in circulation. (The Dalai Lama and the pope are presumably ahead of him, but their sales figures are tricky to quantify.) He owes his dominance of the mind/body/spirit sections of bookshops, in large part, to a mysterious cosmic force beyond all human understanding – specifically Oprah Winfrey, whose championing of his books, including a 10-week online seminar series, watched by 11 million people, has ensured their long-term tenure on bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic.

New age guru stereotype dictates that I should find Tolle bloated by wealth, surrounded by fawning acolytes, an egomaniac in robes and gold chains. But he is none of these things. At home in his pleasant-but-not-opulent top-floor flat in a leafy neighbourhood of Vancouver, he is quiet-spoken and somehow fragile, his elfin frame swallowed up by a brown leather armchair. He really does exude a palpable stillness, responding to questions with several seconds’ thought before speaking; his standard expression is an amiable smile. (During the online seminars with Winfrey, she frequently characterised him as a spiritual leader with the power to transform the consciousness of the planet. Tolle just smiled amiably.)

It is a central plank of Tolle’s teaching that the set of concepts that make up what each of us calls our “personality” is a false construct. This presents a technical difficulty with the whole notion of his being interviewed by a journalist: I want to discover what made Tolle into the person he is, whereas Tolle wants me to grasp that the question of who he is is, in a profound sense, irrelevant. “The person isn’t actually that important,” the 61-year-old says, in a voice tinged with the accent of his native Germany. “People love that kind of thing. They want to know more and more about the person.” He smiles at the absurdity of this. But he is willing, it would appear, to indulge me.

At the time of his spiritual transformation, Tolle had just completed a degree in languages and history at the University of London, graduating with a first, yet he was anything but happy. “I’d done well because I was motivated by fear of not being good enough, so I worked very hard,” he says. With no plans for his future, he grew more depressed until, as he puts it, “I couldn’t live with myself any longer.” The phrase is a cliche, but in The Power of Now, Tolle describes being stopped dead by its implications: “If I cannot live with myself, there must be two of me: the ‘I’ and the ‘self’ that ‘I’ cannot live with. Maybe, I thought, only one of them is real. I was so stunned by this realisation that my mind stopped. I was conscious, but there were no more thoughts.”

When thinking later resumed, as Tolle tells it, things were different: he no longer identified with the “voice in my head” that was doing the thinking. Instead, he could observe his thoughts, as if from a distance. He could see that they somehow weren’t real: that the real him was the consciousness watching the thoughts, not the thoughts themselves. “There was a wonderful sense of peace,” he recalls now. “Not a desensitised peace – you can experience that if you take enough drugs, or drink enough. But a peace that was joyful, and alive, and very alert.”

The intention of The Power of Now and A New Earth isn’t necessarily to trigger a similar sudden transformation in the reader, but to convey a view of human psychology that has deep roots in Buddhism, Hinduism and Sufi Islam. Most of us, Tolle argues, spend most of our lives with a constant “voice in our heads”, that judges and interprets reality, and determines our emotional reactions; if you doubt this, it’s probably because you’re so fully identified with the voice that you can’t see the wood for the trees. There are occasional pauses in the brain-chatter – when gasping in awe at beautiful scenery, doing intense physical exercise, or making love, say – but mostly, we’re lost in thought. We’re especially lost in thoughts of the past and the future. “Most humans are never fully present in the now, because unconsciously they believe that the next moment must be more important than this one. But then you miss your whole life, which is never not now,” Tolle says, chuckling. “And that’s a revelation for some people: to realise that your life is only ever now.”

Tolle’s transformative experience, which happened in 1979, didn’t lead to instant global stardom: commercialising his insights was apparently the furthest thing from his mind. Instead, he embarked on a doctorate in Latin American literature at Cambridge. But it felt meaningless; he dropped out after a year. He spent the next two years in London, sleeping on friends’ sofas, and spending the days on park benches in Russell Square, or sheltering in the British Library. When money ran out, he took a temp job doing office admin for the Kennel Club. “Externally, one would have said ‘this person is completely lost’,” he says. “My mother was very upset, because in her view, I had thrown everything away. And from a logical point of view, that looked quite correct.” His father helped him pay for a flat, and he began to run small group teaching sessions in friends’ living-rooms. But there were many more years to come of what looked, from the outside, like drifting – including a long spell on the west coast of the United States, where he started to write The Power of Now. It was first published in 1997, with a print run of 3,000 copies. (It would be 10 years and one Oprah endorsement later before Paris Hilton would be spotted carrying a copy on her way to jail.)

There are certain contradictions involved in marketing a spiritual message like Tolle’s, however valuable the message itself may be. For example: you shouldn’t make “being more present in the moment” into a goal to achieve, Tolle argues; the whole point is just to be here now, not to lose yourself in the thought of becoming “enlightened” in the future. And yet it’s surely precisely that hope of future attainment that keeps millions of people buying each new Tolle product – not just his books and DVDs, but calendars, and other books consisting entirely of nicely presented quotations from his main two books. He seems only marginally bothered by this. “I do need to be careful,” he says. “I need some kind of organisation, some structure, so that the teaching can get out. But it must not become self-serving, so that the structure” – the organisation, and its profits – “become more important than the teachings.”

He never made a conscious decision to promote himself, he maintains, and it’s hard not to believe him: he isn’t surrounded by a loyal band of followers, and he seems to live, Vancouver penthouse flat notwithstanding, much as he ever did. “I go to the supermarket, I do my laundry, I do my tasks,” he says. “My external life only looks big when I do some event and a car comes to pick me up. But even then, I don’t think ‘I’m going to give a big talk tonight.’ I step into the car, and there is just that step. I look out of the window, there is just that moment.” Gurus who preach the transcendence of ego are prone to having some of the biggest egos around, but it’s a fate Tolle seems genuinely to have avoided.

Tolle’s quiet presence has a way of burning up people’s cynicism, mine included, and yet I still can’t quite believe that life inside his head is as constantly peaceful as he claims. Doesn’t he ever get irritated? “I can’t remember the last time it happened,” he says. “I think maybe the last time it happened …” Earlier today? Yesterday? “I think it was a few months ago,” he remembers, after a while. “I was walking, and there was a big dog, and the owner wasn’t controlling it and it was pestering a smaller dog. I felt a wave of irritation. But what happens is it doesn’t stick around, because it’s not perpetuated by thought activity. It only lasted moments.” And he smiles amiably again.

He lives in Vancouver with his partner of nine years, a Canadian woman named Kim Eng, who often teaches alongside him. (They have no children.) Do they ever have arguments, as in ordinary relationships? “I can’t remember what ordinary relationships are like,” he replies. “Occasionally there are differences of opinion. But we don’t fight. It’s like Obama says – you don’t need to be disagreeable when you disagree. That sounds lighthearted, but there’s a profound truth behind it, because it implies that you don’t need to be totally identified with your mental positions.”

Tolle grew up in circumstances that were decidedly less zen. He was born Ulrich Tolle, in a town near Dortmund, to a matter-of-fact mother and an eccentric, head-in-the-clouds father; they fought, then divorced, and his father left the country. At 13, he says, he abruptly refused to go to school – “I hated having to study things that were not compatible with my inner being” – and his exasperated mother eventually sent him to live with his father in Spain. “My father said: ‘Do you want to go to school here?’ I said, of course, ‘No.’ Then he said: ‘Well then, don’t. Do what you like. Read.'” Tolle credits his unconventional upbringing with broadening his mind. “Spain at that time was very different than Germany, almost medieval. So I didn’t get totally conditioned by one culture. If you live only in one culture for the first 20 years of your life, you become conditioned without knowing it. My conditioning got completely broken, so there was an opening to other world views.” (After his experiences at 29, he marked his transformation by adopting the first name Eckhart, after 13th-century German mystic Meister Eckhart.)

Books like Tolle’s, neither traditionally religious nor rationalist, are sitting targets for criticism from across the spectrum: when Winfrey began promoting him, Christian viewers of her show accused her of trying to start her own church; to hardcore rationalists, Tolle’s ideas are no better than the crystals-and-angels nonsense that clutters the new-age shelves. Both critiques miss the point. At its most basic, Tolle’s message – that we spend our lives largely absent from our lives, identified instead with our thoughts – isn’t even particularly mystical: a moment’s introspection demonstrates it to be obviously true.

Whether or not Tolle’s writing will help jolt you out of your reverie, on the other hand, is largely a matter of your personal taste in prose style. For many, it seems to work, and if they see him in public – despite the baseball cap disguise he wears – they tend to rush over to tell him. This can be awkward. “I’ve always enjoyed being in the background, sitting in a cafe, watching people,” he says. “But now, when I sit in a cafe, sometimes people watch me. It’s a challenge. But it’s usually people who want to say ‘your book transformed my life’, or something … so then I’m joyful. One moment before, I didn’t want them to recognise me, but when they do, I’m glad.”

He shrugs, and smiles once more, giving a highly convincing impression of a man who could lose his celebrity tomorrow and who wouldn’t really mind either way – who might just return, unruffled, to sitting on a bench in Russell Square, watching his thoughts and the world go by.

Tolle on using your mind

‘The mind is a superb instrument if used rightly. Used wrongly, however, it becomes very destructive. To put it more accurately … you usually don’t use it at all. It uses you.’

On problems

‘Narrow your life down to this moment. Your life situation may be full of problems – most life situations are – but find out if you have a problem at this moment. Do you have a problem now?’

On suffering

‘The pain that you create now is always some form of non-acceptance, some form of unconscious resistance to what is. On the level of thought, the resistance is some form of judgment. On the emotional level, it is some form of negativity. The intensity of the pain depends on the degree of resistance to the present moment, and this in turn depends on how strongly you are identified with your mind.’

On life

‘Most people treat the present moment as if it were an obstacle that they need to overcome. Since the present moment is life itself, it is an insane way to live.’

On death

‘Death is a stripping away of all that is not you. The secret of life is to “die before you die” – and find that there is no death.’