by Alanna Kaivalya: Many years ago when I started a yoga practice, I had no idea what it would reveal to me…

I was just hoping for a little extra strength and flexibility, and I did what I could to avoid all the spiritual trappings of the practice. But, somehow, as it does, the yoga did its job. Over the years it brought me through physical, psychological, and emotional revelations that I can’t imagine would have taken place otherwise.

One of the most powerful insights has come through the use of sound and mantra as a basis for the practice. I was born with a hearing impairment that gave me a unique relationship to sound. As a child, I would feel sound, vibration, tone, and intonation in order to more fully access my world. This was second nature to me, but through my studies of yoga (and physics!), I suddenly found a reason behind my special relationship to sound. Just as important, through yoga’s rich mythology, I also gained context and meaning to better understand how the inner and outer practices of yoga work. It is from this perspective that I have always practiced and taught, fueled by the belief that sound has the power to harmonize us and myth brings forth what is alive within us. It is in this spirit that I always end my lectures and workshops with these words: Don’t miss the vibrations.

Mantras and Chants

A mantra, as it relates to the yogic and Vedic traditions of India, is a Sanskrit phrase that encapsulates some higher idea or ideal within the cadence, vibration, and essence of its sound. A mantra can be as simple as a single sound — such as chanting the well-known sound om — or as complicated as chanting a poem that tells a grand story or gives instruction. Whatever mantra is chanted, no matter how long or short, the purpose is the same: it is meant to act like a skeleton key to help you bypass the mundane matters and mental chatter of the day-to-day mind in order to reach a transcendent state of awareness and self-

realization that is, quite frankly, indescribable.

Every yogic practice provides the means for us to do this — such as asana (postures), meditation, and pranayama (breath work) — but mantra practice and nada yoga are uniquely simple and universal. If you can form a thought, you can do a mantra practice. The simple act of thinking a mantra is a start to a genuine practice. The silent repetition of the sound o‡ while driving, for example, can be a starting point. Eventually, our practice might grow to include chanting while meditating, attending lively mantra-based musical performances (kirtan, or kirtana), or perhaps even chanting a longer mantra 108 times aloud to celebrate the New Year. As I’ve said, there is no wrong way to use a mantra.

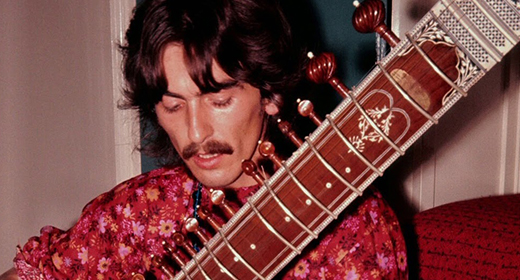

In the United States, mantra has gained popularity largely through the musical kirtan (kirtana) tradition. Popular kirtan musicians such as Krishna Das, Deva Premal, and Dave Stringer have brought these Eastern chants to life by giving them some good old American rock-and-roll flair. While the kirtan tradition in India began around the ninth century, its look and feel hasn’t changed much even as it has evolved to incorporate Western musical proclivities. It has always had (and still has) a fairly simplistic call-and-response-type format, where the leader will chant a phrase that is repeated by the audience. This typically becomes more lively and fast as the chant continues. In India, various instruments are used — typically the harmonium (similar to an accordion in a box), the tabla (classical Indian drum set), and the cartals (tiny cymbals). Those instruments are still present in many kirtan settings today, yet the music is often Westernized through the incorporation of all sorts of instruments, like the guitar, bass, and even a proper Western drum kit (like how Chris Grosso and I perform!). What is wonderful about many of these yogic and Vedic traditions is that they are quite malleable. So long as the intention is still sealed within the practice, the practice — even if it is modernized and Westernized — does not lose its efficacy.

So while some choose to chant mantras in a kirtan setting, others have long used mantra in spiritual practice in accordance with daily rituals, meditation, or as a way to bind fellow students of a tradition. Many use a mantra during their morning worship practice to invoke an intention or particular deity. Many practitioners also stay focused in their meditation practice by silently or quietly chanting a mantra. And some traditions claim certain mantras as part of their tradition — almost like a secret handshake. In many Eastern spiritual traditions, it is common at the beginning and end of a spiritual practice to chant a mantra or om. Mantras are also commonly used as prayers for peace, health, or well-being. Mantras can be used to focus the mind and empower whatever spiritual practice we embark on. Mantra is fuel for the inner spiritual fire.

In truth, you don’t need to know or do anything more to use mantras in your own daily practice, but don’t be afraid to experiment and try something new. Read through all the mantras in this book. Say them out loud. If any resonate with you, keep using them. Sometimes people are reluctant to chant mantras they don’t know the meaning of, but that is one reason I wrote this book! Also, keep in mind that there are many more mantras than appear in this book, and all are efficacious. Mantras are beneficial compilations of vibration that help to uplift you.

Finally, if you are brand-new to yoga or Eastern spiritual practices, know that chanting mantras doesn’t make you a Hindu. By chanting, you are not joining a religion or expressing your belief in any religious dogma. The aim is spiritual, not denominational. The power of mantra lies in the vibrations, and these vibrations work on many levels, whether the sayings are pronounced out loud or silently, correctly or incorrectly. The benefits of chanting do increase with more accurate pronunciation — just as pronouncing any foreign language correctly makes it more intelligible — as well as with better understanding of the meanings, but the simple act of saying a mantra will still bring the mind and heart into alignment with its subtle goal, which is to bring heightened self-awareness and a deeper sense of peace and calm.

With that in mind, I encourage you to simply begin a mantra practice in whatever way that feels right. Start simple, such as with om, and incorporate other, longer, or more complex mantras as they resonate with you. Some mantras may appeal to you because of their sound, while others may become attractive as you understand their context, underlying mythology, and intention. Over time, as you use each mantra in your life and practice, it will become like a friend whom you come to know more and more deeply. The mantra may start out as a little gem that lightens your day, but after years of saying it, it may also become a bright light that guides you through the darkest of times. Through practice, we make these mantras our own so they help us on our spiritual journey.

The Historical Context of Mantra Practice

The mantras compiled in this book come from a variety of sources within the vast scope of the Vedic tradition. The Vedic tradition is a broad term that defines the text and rituals coming out of the historic Indus Valley, and it is based on one of the world’s most ancient spiritual texts: the Veda (a.k.a. Vedas). Many Vedic texts are said to have been simply “received” by ancient saints (called rishis or rsi) as opposed to being authored by a specific person. It is from the tradition of the Veda that we derive the original practice of mantra. These historic source texts were founts of wisdom that were unlocked by those who could read them — namely the Vedic priests. They would bring the knowledge and tradition of the texts to the people via ritual chanting and fire ceremonies. Even today, chants like the Gayatri Mantra are largely unchanged from their Vedic roots.

Over time, other important source texts arose within the Eastern spiritual traditions, and more mantras emerged from them. For example, the Purana (Puranas) are the source of much of the mythic history of the East. They contain mantras and have been the source of inspiration for modern mantras. Many of our current spiritual and yogic leaders in the West have looked to the Purana for mythic inspiration, and they have written simple kirtan chants to invoke the energy and essence of various iconic deities. Mantras also embody the focus of specific spiritual traditions. For example, the Maha Mantra of the Krishna Consciousness tradition helps practitioners enliven and enlighten their spiritual quest for a deep, internal relationship with Krishna (Krsna).

Mantra represents an unbelievably accessible and widespread tradition, one that extends from the millennia-old mantras of the Veda, which are chanted widely in yoga class and teacher trainings, to the contemporary composers of the kirtan tradition, who have brought mantra to life with a Western twist. Mantras remain popular in today’s spiritual practices, and yet modern-day spiritual practitioners have had no single resource that brought them together and illuminated them. I hope this book fills that need, for after all, knowledge is power. Tracing these venerable vibrations to their source shows us not only the history of the yogic practice but also how we have evolved it and moved it forward to suit our current needs and cultural matrix. Because mantras are of no use if they don’t speak to our modern-day psyche.

How to Chant: Some Practical Instructions

There are no hard and fast rules for chanting. It can be done silently or aloud, in a group or on one’s own. The act of speaking the mantra (even silently) allows the mantra to do its job. However, you can strengthen and improve your practice by also focusing on the meaning of the mantra and pronouncing the Sanskrit correctly. Even so, without any intention and with halting pronunciation, you will still derive a benefit from a mantra practice, just as for someone trying to get into shape, any exercise is good exercise.

Whether you are new to chanting or not, here are some general tips for chanting and for developing or improving your mantra practice:

To start, practice one chant consistently for as little as five minutes a day. It could be a vocalized repetition of the sound of om in the shower, or quietly repeating the Gayatri Mantra upon waking. Get into the habit of speaking Sanskrit regularly. Get used to the patterns and sounds, and soon the chants will come more easily and naturally. Match saying the mantra with the regular, steady rhythm of your breath. This will help the mantra to regulate your autonomic functions and put your breath, body, and mind into better alignment. If you practice this regularly, you may find that the mantra appears in your head throughout the day as a touchstone of steadiness and stillness. That’s great — it means the mantra is working!

Choose a chant that resonates with you, and incorporate it within a meditation practice. If you don’t already have a meditation practice, starting one is actually very simple. Find a quiet, comfortable place, sit up nice and tall, and close your eyes. Then either silently or quietly chant the mantra. If you haven’t memorized the chant, lay this book out in front of you, open to the proper page, and say the mantra over and over until there is a natural flow. While you chant, let the mantra fall into rhythm with the pattern of your breath. If you are saying the mantra out loud, focus on the vowels, as this is the source of the most powerful resonance. If it helps, place one hand over your heart to feel the vibrations inside your chest.

While there is no wrong way to chant a mantra, it is nice to adopt a style or mode that is either “common” or “traditional.” The style of Vedic chanting has only three tones: the one you speak at, one tone above, and one tone below. This makes it easy for everyone — no matter what your voice sounds like — to try and chant. A good example is the Asato Ma chant, which you can find online in my website’s mantra library. It is a prime example of this style of Vedic chanting. Some modern-day teachers and kirtan singers make the mantras sound fancy and more sing-songy, but they don’t need to be. Start simple. Find a rhythm and a tone that works for you and keep at it.

If you like kirtan — the lively practice of call-and-response chanting set to uplifting music — sing along! Seriously. Put on a kirtan CD and sing along as if you are part of the crowd. The great music of the kirtan style will liven up your mantra practice, and if the spirit moves you, grab a tambourine, stomp your feet, clap your hands, and let the spirit of the mantra carry you away. Chanting kirtan is typically call-and-response, but this doesn’t mean you can’t do both the call and the response. If you’re alone, sing all the parts to yourself. When kirtan chanting is done in groups (such as in yoga class or at a concert), a leader “calls” and the audience “responds.” It is a simple practice — it is meant to be. This helps make it universal and accessible.

If you attend a yoga class, kirtan, or satsanga (a.k.a. satsang, a spiritually-based group event), you may find that the teacher will chant a mantra differently than you learned it. If so, just go with the flow and focus on the vibration and intention of the chant. You may even discover that you like this version better! Also, some mantra practitioners believe that there is only one correct way to chant each mantra, but this just isn’t so. If this were the case, then mantras would only be efficacious when chanted in a particular way, and there is no evidence for this. The most traditional Vedic schools of chanting maintain a simple rhythm and pattern for some mantras, but those mantras can also be dressed up in a kirtan-type setting. Not only is this okay and appropriate, but it can breathe new life into them!

Whether chanted in a traditional or modern setting, on your own or in yoga class, with or without music, silently or aloud, mantra will move you. It will touch the deepest parts of yourself that few other spiritual disciplines can reach. Start with a mantra practice that feels comfortable and expand your horizons from there.

Same Source, Separate Traditions: Yoga and Hinduism

The universality of these mantras might be one of the reasons why they (and their source texts) have stood the test of time. While many spiritual traditions have songs or chants that express wholeness, compassion, and unity, the eloquence with which Vedic and yogic mantras express these uplifted human values has a lyrical quality that unlocks the heart of the practitioner in ways that we cannot imagine, but only experience. While the mantras have long been practiced as a part of the yogic tradition, the growing popularity of yoga in the West has made them accessible as exceptional tools to heighten the experience of our spiritual practice. As the mystical arm of the larger Vedic tradition, yoga is a way to enhance our spiritual depth and strengthen our belief system, even if it differs from yoga’s Vedic origins.

Yoga evolved around the Vedic and Hindu cultures in India, and so its wisdom incorporates a lot of the same language, mythology, and philosophy. However, yoga differs in that it points the practitioner inward, to the mystical or esoteric source of internal spirituality, similar to the way that Gnosticism does within the Christian tradition, Sufism within the Islamic tradition, and Kabbalah within the Jewish tradition. While certainly related to Hinduism, yoga doesn’t require participants to embody the religious aspects of the Hindu tradition. This is similar to the way people — like Madonna! — have incorporated Kabbalistic practices into their daily repertoire in order to enhance their spiritual well-being. In general, the mystical traditions of most religions are designed to lead us inward, to our highest state of being, rather than outward to an externalized expression of faith.

Though yoga evolved alongside Hinduism and is sourced from the same Vedic wisdom, their intentions are fundamentally different. Yoga leads practitioners to an internalized, mystical, and esoteric understanding of their highest self. Hinduism focuses outward to the more traditional and canonical structure of the faith. Like a pair of siblings who grew up in the same household, one an extrovert and one an introvert, Hinduism and yoga have a shared history and a common goal, but different means of getting their points and practices across. So, while many of the myths, texts, and philosophical underpinnings found in this book may have a shared relevance across the Vedic, yogic, and Hindu traditions, our point of view will be through the yogic lens — the lens that shows the internal structure of our highest self.

The Universality of Yogic Mythology

One of the exceptional aspects of the yoga tradition is its all-inclusive nature. It accepts all practitioners, no matter what their original spiritual or religious background, and helps them experience the numinous in their lives. But, because the numinous cannot be named or described, the number one way in which this kind of psychological and spiritual information is conveyed is through mythology.

Mythology is the language of the unconscious. It gives shape, meaning, and context to the archetypes of the collective unconscious, and that allows us, in turn, to give shape, meaning, and context to the stories that play out within our lives. Mythology is an essential part of our human psyche. And it is critical to cultivate a meaningful mythology within each of our lives. This is particularly important in our modern world, when so few traditions, religious and otherwise, provide this. Perhaps we grew up within a religious tradition that, for whatever reason, we have since walked away from, but it is important that we still continue journeying toward a mythology that enlivens our psyche — that gives our life meaning. We need to find out, as Carl Jung asked himself, what myth we are living by.

What is a myth? Put most simply, myth is metaphor. Joseph Campbell often described myth this way. As he explained, through metaphor, we are better able to understand ourselves and the world. For example, in the myth of the Bhagavad Gita, the hero Arjuna has an intense dialogue with his chariot driver, Krisna (Krishna). Arjuna is about to go into battle, and seeing that his enemy’s army is both enormous and partly composed of his family and friends, he is filled with doubt and tries to chicken out. This metaphor speaks to all of us. We can all imagine ourselves as Arjuna, faced with the challenge of the spiritual journey. As we cope with our own fears and doubts as we approach our life’s battles, we can turn to the myth of Arjuna to provide a meaningful perspective on our own situation.

Myths aren’t necessarily true in the empirical sense — even when they refer to real, historical figures and actual events. Myths embody deeper truths about the nature of life, and they often embody important guidance or life lessons. Myths bring meaning to our lives and help us to navigate life’s difficulties like an old friend leading us by the hand. From the yogic perspective, myths help guide us on the journey inward, which is possibly the most fruitful journey there is.

Mythology helps us cultivate and deepen the relationship between the ego and the higher self, between ourselves and those we love, and it helps us bring forth what is alive within us into the world. Mythology gives us the tools, means, characters, rites, context, and lessons so that we can then live, embody, vivify, and restore the verve to our life.

As it turns out, the yogic tradition has awesome mythology. The rich stories found within the original source texts — whose history spans millennia and whose true authors remain cloaked in mystery — help shed light on the challenges, trials, and tribulations of life. While precise dates are largely unknown, we surmise that the Vedas, widely regarded as the world’s oldest known spiritual texts, are at least five thousand years old. The Vedas laid the extensive groundwork for the Indus Valley tradition, but beginning somewhere around 1500 bce, their grand scope was eventually distilled into the more concise spiritual texts known as the Upanisad (Upanishads). Around the start of the Common Era, we start to find the riches of the story-filled Purana (Puranas). All of these texts feature an enormous body of rich mythology that provides us with fantastic metaphors for life and the human condition.

Though these truths are universal, the shapes that they take within the yogic mythological tradition are highly varied. There are said to be 300 million gods in the Vedic pantheon. Alain Daniélou, author of The Myths and the Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism, states it eloquently this way:

Hindu mythology acknowledges all gods. Since all the energies at the origin of all the forms of manifestation are but aspects of the divine power, there can exist no object, no form of existence, which is not divine in nature. Any name, any shape, that appeals to the worshipper can be taken as a representation or manifestation of divinity.

In other words, all manifestations of yogic mythology are simply reflections of one numinous source, and they provide endless avenues by which we can discover that source within ourselves. Or, as Eknath Easwaran, student of Gandhi and founder of the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, once described this, “Yogic myth has the genius to cloak the infinite in human form.”

Excerpted from Sacred Sound: Discovering the Myth and Meaning of Mantra and Kirtan, published by New World Library.