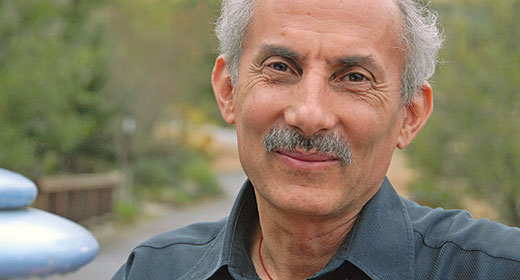

by Jack Kornfield: The next three steps of the Eightfold Path have to do more with inner work of meditation than outer work of Right Livelihood and Right Speech, and so forth.

The next step is called Right Effort. It’s very important in understanding spiritual practice.

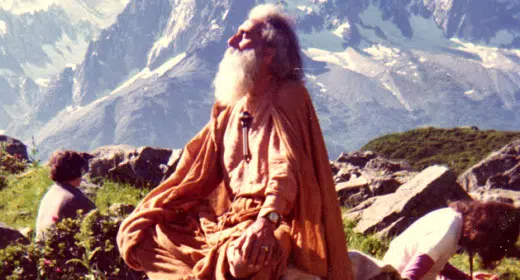

Ramana Maharshi, the great Indian master, one of the greatest ever, and certainly in the last century or so, said:

Enlightenment is not your birthright. Those who succeed do so only through proper effort.

It was an amazing thing for him to say because he became fully enlightened at seventeen years old when he went to his uncle’s house and said, “I wonder what it would be like to die. I think I’ll try it.” And he laid down on the floor and died, and then came back somehow. It’s hard to know whether he physically died, but it seemed like he died, and he came back with a very different perspective on life. Nevertheless, he taught for many, many years, and even he said this.

One day Nasrudin went to the market with a recipe for some kind of liver and kidney pie, or something like that, and he bought the meat. He had the recipe in one hand and he took the stuff for his pie in the other hand. And a huge raven or crow saw him walking home and swooped down from a tree nearby and grabbed the meat out of his hand and flew off with it. And Nasrudin shook his head and said, “It won’t do you any good. You don’t have the recipe.” It gets kind of reversed for us. Most of us, especially living in California, as we do, are overburdened with spiritual recipes. How many Dharma talks, how many spiritual books, how many retreats, how many good therapy things, how many sesshins, and how many whatever have you had? You have the recipe.

Like all the people sitting under the bodhi tree with the Dalai Lama, and the pilgrims who had come from miles and miles on foot from the high Himalayas to be with the Dalai Lama in Bodhgaya, he said, “Okay, you’re here, and you think you’re very fortunate because you have the blessings of being under this bodhi tree where the Buddha was enlightened, with all these famous lamas, and the Dalai Lama himself, and you have the teachings, the sacred meditations, and mantras, and all these things. It won’t do you any good. The only thing that makes it work is if you take the trouble to practice it. All the rest of it is very nice, and you might as well watch Dallas or something like that. It’s not so different. Maybe you would learn more from Dallas, I don’t know. At least it wouldn’t be pretentiously spiritual.” So the answer is “effort.” Effort is central in our spiritual practice. Traditionally, there are four kinds of effort that are talked about. The effort to deal with unskillful things has two parts.

First, the effort to abandon that which is unskillful, and that means abandoning our grasping, our fear, our hatred, or our anger. It doesn’t mean judging oneself or resisting it. It means learning skillful means not to be so caught up in things, not to be so attached. Then, the effort to maintain their absence, once you’re figured out how to let go of them some. It’s like Mark Twain and smoking. You all heard that. When someone asked if he had ever stopped smoking, he said, “Sure, it was easy. I’ve done it thousands of times.” The second effort is the effort to maintain that abandonment in some fashion.

The other two traditional definitions of Right Effort have to do with that which is skillful; the effort to develop or cultivate or nourish that which is skillful within ourselves, and then the effort to maintain or sustain it, so that in some fashion it stays with us. This is from the Dhammapada:

One person on the battlefield conquers an army of a thousand persons, Another conquers himself, and that is greater. Conquer yourself and not others, discipline yourself, and thereupon learn freedom.

So it’s the effort of learning how to cultivate or generate that which is skillful — which means awareness, loving-kindness, or caring for the world around you, or living more in the present, the effort to abandon the habits, the fears of things that we get caught in that create suffering and that keeps us in the muck, and the effort to sustain them. This is wonderful because it’s a teaching that can apply very much to our daily life; it’s not just a retreat teaching. It’s small habits and all the little pieces.

Our life is made up of little activities, little pieces, little habits, and little ways. And we can begin to work with the way we drive our car, the way that we relate to people at work, or the way we eat, what we choose to eat, and how we set about eating — to make those things more conscious. To make our approach to these bear the fruit of greater awareness, greater attention, of more caring, of more kindness.

Think now for just a moment: what are a few things in your own life that could well be served by bringing a little more of this effort, this effort to pay attention, or the effort to let go and abandon? What little things do you do that you could use in some way to wake up more, to awaken? Fundamentally, the meaning for Right Effort can be expressed in a simple way: it’s the effort to be aware, the effort to see clearly, to pay attention. That’s Right Effort. One Zen master was asked, “Would you give me the essence of the teachings?” He wrote down, “attention”. Then the person said, “Fine. Now would you give me the whole teachings, the commentary, and how I should undertake it?” He wrote down, “Attention, attention.” The person said, “Isn’t there anything else?” And he said, ‘Attention, attention, attention. That is it, to be present, to see clearly.”

Right Effort isn’t so much the effort to make the world a different place, as it is the effort to understand the nature of this world, of our body, our mind, this life. Why is it hard to make the Right Effort, why is it hard to pay attention? It’s hard for different reasons. It’s hard because we sometimes don’t want to see. You know, this idea of “Be Here Now,” and so forth, it sounds good,.It’s not so good. It isn’t, because what happens when you’re here now? Has anybody looked? What do you have to be here now with? Pain, boredom, fear, loneliness, pleasure, joy, beautiful sunsets, wonderful tastes, horrible experiences, people being born, people dying, light, dark, up, down, parking your car on the wrong side of the street, getting your car towed; all those things. For if you live here, it means that you have to be open to what Zorba called “The whole catastrophe.”

Sometimes we don’t want that. Right effort is the effort to see clearly. This world is crazed. There’s war, there’s prejudice, there’s political prisoners, there’s all this kind of suffering that we need to remember living in Marin, because it’s really kind of a ghetto that we live in, and we forget how incredibly fortunate we are. I had a letter today from someone I know . She’s kind of middle-aged and very poor, and just gets by doing some sewing, and her husband works in a gas station. They live in Florida. They are related to some people I know. They’ve had a very hard life. She has some kind of progressive degenerative disease. They do not live in such a nice neighborhood, and their house was broken into, and the few things of any value that they had were just stolen. I thought, “God, here I live in such a nice place, and have nice things, and I leave the front door open most of the time, and don’t worry about it,” and we forget what blessings we have. We forget about the sorrow and the struggle in the world. Part of the effort is to really wake up and to look at ourselves and at the world around us, and to be conscious of it, not to be just asleep.

My teacher Achaan Chah said there are two basic ways of practice. One way of practice is to be comfortable. And it’s valuable. You can sit a little and get yourself quiet. You keep the precepts, so you don’t harm people, and they start to like you. You say “Om” at dinner. You chant a little before you eat. And everything becomes nicer in your life. It becomes more comfortable and more pleasant because you live a good life and you’re peaceful. The other way to approach spiritual practice is not to be involved in trying to be comfortable, but rather to be free or liberated. And that way of practice has nothing whatsoever to do with comfort. Comfort may come and it may not. Sometimes it may be terribly uncomfortable, but its goal or its direction is not comfort; its goal is freedom.

It’s a wonderful thing, and it’s a real legacy of the Buddha. Right Effort means we really need to start to pay attention, and to see how fortunate we are, and to begin to see the laws that govern the world within which we live. Another friend of mine just called me this week and said her husband who is in his mid-forties has advanced lung cancer; he just found out about it a few days earlier. Then she called about four days after that. She asked me what was the lesson in that. She said, “You’re a teacher. Tell me what the lesson is.” I don’t know what the lesson is. I said, “I don’t know. Call me later, maybe I can think of one.” And she called back. If you trust people they generally find out what the lesson is anyway. She said, “I know what the lesson is.” I said, “What?” And she said, “The lesson is to love people while you have them, when they’re here.” It was so sweet and so touching because it came from a place where she really, really knew it. It’s to take care with what we have that’s beautiful, and nourish it; and that which isn’t, to abandon it.

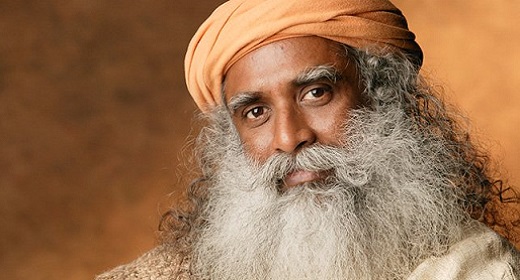

I’ll read you a passage from Nisargadatta Maharaj, the old bidi wallah who I studied with in Bombay; wonderful old teacher. He sold little Indian cigarettes on the street corner, and he was fully enlightened somehow at the same time. He had these classes. He died a couple of years ago. He was a wonderful old man. Someone asks:

What can truth or reality gain by all our practice?

He uses truth and love interchangeably. He says:

Nothing whatsoever, of course. But it is in the nature of truth or love, cosmic consciousness, whatever you want to call it, to express itself, to affirm itself, to overcome difficulties. Once you’ve understood that the world is love in action, consciousness or love in action, you will look at it quite differently. But first your attitude to suffering must change. Suffering is primarily a call for attention, which itself is a movement of love. More than happiness, love wants growth, the widening and deepening of awareness and consciousness and being. Whatever prevents that becomes a cause of pain, and love does not shirk from pain.

That’s an amazing thing to say, that love doesn’t shirk from pain, that what loves wants is not pleasure. You live in Marin, you know about pleasure. It’s wonderful, but it gets boring after awhile. It does! There is something deeper or higher, that’s richer, that is our capacity, or our birthright, or our deepest need. I don’t know what it is, but it is different than just pleasure. What does it mean to make Right Effort? We’ve touched this, or we want that, or we want to discover or open. There are two different approaches or styles to effort. I’ve practiced with them both, and I’ll put them out, and you can listen and see which works better for you. One is the Rinzai approach, using Zen terminology, where there is enlightenment, and it’s a goal, and you work very hard – you literally bust your ass on your cushion or whatever you do to get to satori or kensho or enlightenment, and you really make an effort directed to this goal.

One of the ways of practice in the Theravada tradition that I’d done in the Sun Lun Monastery was to sit without moving a minimum of four sittings a day of two hours. The first hour was heavy breathing, where you sat and did as full and deep breathing as you were capable of for an hour. And the sayadaw was sort of like a football coach, and he would come around and say, “Harder, more.” And you concentrate on it. You get very concentrated in an hour. If you were sleepy it woke you up; if you had thoughts it kind of blasted them out of your head; and by the end of an hour you were very present. Then the next hour you continued to sit without moving, and used that concentration just to be with what your experience was. It was very powerful.

Or the kind of effort in the Mahasi Monastery where I practiced where you sit and walk l5 or l6 hours a day, or l8 if you can. You sleep for four hours and you eat a little bit. You sit motionless, you don’t move, and the sittings are shorter, 45 minutes or an hour, and you don’t make a a movement without paying attention to it. Lift your hand, blink your eyes, “blinking, turning, moving.” You pay attention to every single little thing. Why do that? It sounds so hard. It is, it is very, very hard. And if you start to do it, all the defilements, all the desires, all the fears, all the reasons that you keep yourself spaced out and in fantasy, and don’t want to pay attention, they all come at once. Like this wall. And you just sit, and you just walk, and you do it. The purpose is to dissolve the sense of solidity of the world. If you pay attention that carefully, and that fully, or that deeply with concentration — that’s next week’s talk on Right Concentration — you begin to see that what’s solid is not solid, and that what seems as “I” or “body and mind together” starts to dissolve into all these little parts.

There are the four physical elements, the different mood states, and consciousness, hearing, seeing, smelling, and tasting. And that’s all there is! And it takes the whole show apart, but it takes a powerful concentration and a sustained attention to do it. It really is going through fire. There’s even a physical transformation. There’s a book I read recently by Ireena Tweedy called “Chasm of Fire”. She’s this old Sufi lady who worked with this master in India. She talked about her experiences, more in the Kensho metaphor, but it’s not so different. It’s really sitting through the fire and letting your body, your desires, and your fears, just burn through you, and you just sit. After awhile your attachments to things change and you become much more detached from this that we take to be ourselves, this physical body. And you become more detached from the fears and feelings, and all of those things. You start with that detachment; then you see it as it operates, clearly, because you’re not so incredibly identified with “I, me, mine, my body, my mind.” It’s very powerful!

Suzaki-roshi teaches Zen sesshin in a very strict fashion. Or Chan Hsun Hua who runs Gold Mountain Temple. He used to have 49-day chant sesshins in San Francisco. You sit for 49 days, and you sleep sitting up, you sleep in your place. I never wanted to do it. I’ve thought about it. For some people it’s terrible because they’re already tight and they do it and it just drives them crazy, it makes them tighter; and it doesn’t bring any enlightenment at all; it just brings pain. But for some people it’s a way of practice, the effort to concentrate, the effort to pay attention, to bring yourself back — again, and again, and again. It’s not the effort of tensing your body, but it’s the willingness to sit with anything, and keep bringing your mind back, or to walk with anything, to really do that. Gurdjieff says:

If a person gives way to all their desires, or panders to them, there will be no inner struggle in them, no friction, no fire. But if for the sake of attaining liberation, they struggle with their habits that hinder them, they’ll create a fire which will gradually transform their inner world into a single whole.

That’s one way of undertaking practice. And when you look at how powerful our habits are, and how much we go to sleep, and how much the world really needs somebody to have the courage to say “no” or “stop” or “wake up” or “live differently,” it becomes very compelling. I know that you’re not on retreat, that we live in busy household lives — but the same spirit, this kind which is just half of the effort I’ll talk about, can be brought to your daily life. It can be the effort to do whatever it happens to be in your life that you know is really going to make a difference. So one can bring that effort, and it’s a wonderful thing to do. And if you learn to do it — it takes practice – it’s really empowering; it brings a certain inner strength with it as well.

The other approach to Right Effort is actually a bridge between these two that would be nice to read about. Someone recently gave me this book called “”Peace Pilgrim.” It’s about this woman who walked around the country for 20 years wearing her blue jogging suit that said “Peace Pilgrim” on it, carrying a toothbrush. She spoke about peace, that you had to make yourself peaceful and the world peaceful. She never took food unless it was offered to her. She fasted otherwise. And she never took rides until much later in her life. She just walked and talked about peace. And this is her story, and it’s a fantastic book. She said:

During my earlier spiritual growth period — The ten years that she was getting prepared to do her peace walk — I desired to know and do God’s will for me. Spiritual growth is not easily attained, you know, but it is well worth the effort. It takes time, just as any growth takes time. One should rejoice at small gains, and not be impatient, as impatience hampers growth. The path of gradual relinquishment of things hindering spiritual progress is a difficult path, but only when relinquishment is complete do the rewards really come fully. The path of quick relinquishment is an easy path, for it brings immediate blessings, and when God fills your life or the truth fills your life, the gifts overflow and bless all that you touch.

What she said is very beautiful. It takes time, just as any growth takes time, and it’s not easily attained but well worth the effort. If you do a lot of it, you get a lot of reward; if you do it slowly, which most of us do, then it’s a little more frustrating because a lot of the reward comes when you’re much, much freer. It’s the way it goes. What can you do? It’s still worth it. It talks about both these kinds of effort, that if you’re willing to make the effort to really do a lot, or let go of a lot, or transform your life, then tremendous fruits can come. You can change how you live this week, how you relate, or you can take it slower.

The other kind of effort is not goal-oriented, to get to kensho, or satori, or enlightenment, or dissolve the world, transcend yourself; it’s the Soto Zen approach. It’s the approach that says that you’re already enlightened. And that is enlightenment; it’s not something else. It’s just what’s here. And the only thing that blocks our enlightenment is all these thoughts that say, “This isn’t enough; I want it different.” If you could just live with things as they are; that’s all; this is it.

Krishnamurti speaks about it very beautifully when he said:

It’s the truth which liberates and not your effort to be free.

“All year I’m going to get this, and be that, and now I’ll be –” I remember when the first interesting meditation practice experiences started to come, I got very excited, and my mind started to fill with thoughts again. There were these lights and things, and I thought, “Gee, this is really exciting,” because I started to think about what I’d do when I was enlightened, who I would go visit and what I would say. It’s like that ego, that part of us that wants to take it as a kind of a merit badge or something that you can wear; or a degree. And it’s not that at all. It’s to live with things as they are, to see them clearly, directly, and truly in each moment.

Ramana Maharshi said:

There are two paths to awakening. One is that of self-inquiry, where you look to see.

The main koan is, “Who am I?” or ” What am I?” And you do it through awareness; or through whatever training that you can, to discover and investigate the body and mind. And the other is the path of surrender, where you say, “Not my will but thine.” It’s actually the same if you really look at it. “Okay, in this moment I’ll be aware of what’s here without trying to change it and just see what it is.” In that awareness you start to see the truth of it — that it’s impermanent — that it’s not “I, me, mine”; that it’s not self; that we’re not separate; then it begins to reveal its nature.

This way of effort then is the effort more of surrender, of letting go, rather than trying to attain something. It’s surrender to be in each moment in a balanced way. Don Juan says:

If one is to succeed in anything, the success must come gently. With a great deal of effort. But with no stress or obsession.

So it’s rather the effort to be here again and again and again, and to truly see that things arise and that they pass away; that they’re born; that they die; that we don’t own anything; that none of it is ours. Our thoughts, do you control your thoughts? Does anybody here have control of their thoughts? We think that they’re ours. Or our bodies. We do a little better at that, but not very well, if you look at it. There’s something I want to read. I’ve been reading all these books on early child development and labor and whatever. It’s from a book that I’ve come to appreciate very much called “Whole Child, Whole Parent.” If anyone is looking for a spiritual guide to parenting, it’s the best that I’ve found. It’s called “Zen and the Art of Throwing a Ball.” It gives a much more Taoist sense, instead of making the effort to come back again and again and dissolve the world. This is the way of effort which finds the Tao within our movement, the way that we live.

The self — the self-centered sense of us — knows that freedom has something to do with law and order but thinks that order must be brought about by will power. The child shows us that, on the contrary, freedom comes through subservience to existing order, to the Dharma, through conscious alignment with it. The self knows that freedom has something to do with pleasure, but it thinks it means feeling good and being above the law is what pleasure is. The child shows us that this pleasure is really spontaneity and that it too is a by-product of absolute compliance or obedience to the law or the dharma. Here’s a story:

Once I heard a father marvel, “How did he learn to throw that ball so far? I didn’t teach him. When did he learn to do this? I didn’t even see him do it? Why did he do it? No one in our family is particularly interested in baseball, and yet he did.” Everything that father thought might have been a hindrance. had it actually been present. The family’s interest in baseball or someone watching him, or anything. Somewhere along the way, in the throwing of a ball, the child had conceived of a possibility of freedom. Perhaps it first came through watching someone else, perhaps once in flinging a ball, he had let it fly and surprised himself.

At any rate, some freedom had been encountered and was now a possibility in his consciousness. After that, as long as he remained unself-conscious — which means undivided — he was able to give his undivided attention to the possibility of which he had conceived. Through his pure desire for freedom in the sense of possibility, certain laws were given the opportunity to gain power over the child. Aiming himself toward a conscious possibility he became subservient to it. And then through the child’s receptive and devoted consciousness the underlying force of being, itself, organized and energized and utilized and coordinated everything in the child to express himself in the form of freedom to throw the ball so beautifully. He must have practiced for hours on end, expending tremendous effort but little strain because his interest in seeing what was possible carried him along, confident that what he could conceive of was possible and could be realized if he went at it.

Sometimes the ball fell short but he did not infer that he lacked power. Sometimes the ball went wild, but he did not infer that the thing was impossible or that there was no predictability and all was chaotic. Whatever seemed too hard only showed him that he had not yet discovered the knack. Whatever appeared chaotic only suggested that the order and his oneness with it had not yet been discerned. Sometimes his shoulder hurt, but the very hurt became a guide, directing him into better alignment with the hidden force he did not doubt. He looked at everything for what is and what isn’t, and everything taught him, until he could throw the ball far, fast, accurately and with remarkable ease. And he wasn’t proud. He wasn’t too pleased, and he didn’t feel triumphant. He felt grateful. And he didn’t feel powerful, he felt surer. And he felt free and was freer. It was never that he had his way with the ball, rather through his undistracted, absolutely focused, unselfconscious attention, the invisible laws of physics had their way with him. through the total submission of himself to the invisible laws, he found both dominion and spontaneity which he rightfully experienced as true freedom and joy.

What a wonderful way to learn. It speaks to this other meaning of effort, and it also speaks to a kind of secret about the first kind of effort, which I’ve used a lot in practice, and gained from in some ways. And that is, in the end you have to let go. No matter how much effort you make and where it takes you, it doesn’t take you all the way, because it’s not your effort that makes you free but your discovery of what’s true about yourself, and life, and its changing nature and the laws of it; that you come into harmony with it, that you become free. It can be big things. It can be a big satori and a big awakening.

Sometimes you get hit over the head by someone near you getting cancer or a near car accident, or it can be little things, like a child, where you just begin to take your life as a discovery, and you start to see what are the laws that operate that make people happy, make them unhappy, what are the laws that operate that make war and make harmony or peace between people. I got a letter recently from someone who had been in one of these classes asking about the question of enlightenment. We talk so much about precepts and following them, and Right Speech and Right Action, what about enlightenment, where does it fit, or is this just a system of ethical conduct? Is this Buddhism? The Buddha said it quite explicitly a number of times in one very beautiful sutra. He said:

The reason for my teaching is not for merit or good deeds or good karma, or concentration, or rapture, or bliss, or even insight. None of these is the reason that I teach, but the sure heart’s release. This and this alone is the reason for the teaching of a Buddha.

All the other things are secondary to it, secondary to what that child experienced with the ball or what the old bidi wallah talked about of the movement of love. It’s not compelled by pleasure, not by precepts, not by success or failure, but by learning to grow, learning to open, learning the laws of the world, learning to connect. There is enlightenment, there is freedom, it’s true, it’s absolutely true; and you can experience it; you can come to that. It says in the Dhammapada that:

To live one day and taste very deeply the meaning of impermanence is better than living l00 years and not to touch it.

Why could that be so? Because to taste that, even for a moment, is that you see what’s true about life and you start to live out of that truth more fully. You become free, which is what we all want most deeply. . I ask you a few questions. Think about Right Effort for a moment. Where are you making too much effort in your life? What things do you do where it’s too tight and too hard? You need to learn balance. Can you think of them? Where do you try too hard or grasp too much? Where do you make too little effort in your life? Where are you lazy or habitual? What aspects of your life could be ennobled or awakened with more effort? Think about them. Which ones? Where is your life too internal? Where do you shy away out of fear from the world of events and circumstances around you? Where is your life too external, or you don’t sit enough, you don’t take enough silence? You don’t listen inside to your heart, to what you care about, make it inform your life.

To listen in this way inside is to discover the laws like throwing the ball of Right Effort in your life. Where do you miss the mark? Practice a little more. What takes more effort, what takes a little less? What takes more solitude? What takes more giving, and loving, and serving? You actually know the answers to those things. They come pretty easily to us. We just forget to ask, or we don’t want to ask because it means, “Ugh, I have to rearrange my life yet again in some fashion or other.” But it doesn’t really matter, because that’s the game. Everything gets rearranged anyway. Either you can rearrange it or you can wait for it to be rearranged. It’s also the game; to grow. So you can stall it for awhile. If you really drag your feet, you can; but it’s not as interesting. I’ll close with my question to my teacher Achaan Chaa.

I still have very many thoughts, my mind wanders a lot, even though I’m trying to be mindful.

He said:

Don’t worry about this, try to keep your mind in the present. Whatever there is that arises in the mind or the heart, just watch it, let go of it. Don’t even wish to be rid of thought, then the mind will reach a natural state, no discriminating between good and bad, hot and cold, fast and slow, no “me” and no “you”, no self at all, just what there is. When you walk, no need to do anything special, simply walk and see what there is. No need to go to a cave or cling to isolation. Wherever you are, know yourself by being natural and watching. If doubts arise, watch them come and go.

It’s very simple. Hold on to nothing. It’s as though you’re walking down a road, periodically you run into obstacles. When you meet difficulties, see them and overcome them by letting go. Don’t think about the obstacles you’ve passed already, don’t worry about the ones you haven’t seen yet. Stay in the present. Don’t worry about the length of the road or a destination either. Everything is changing. Whatever you pass, do not cling to it, and eventually the mind will reach its natural balance where practice becomes automatic and effort becomes effortless. All things will come and go of themselves. Sitting hours on end is not necessary. Some people think that the longer you sit the wiser you must be. I’ve seen chickens sit on their nests for days on end.

Wisdom comes from being mindful in all postures. Your practice should begin as you awaken in the morning and continue until you fall asleep. What is important is only that you keep aware, whether you’re working or sitting or going to the bathroom. Each person has their own natural pace. Some of you will die at age fifty, some at age sixty-five, and some at age ninety. Don’t think or worry about this. Try to be mindful and let things take their natural course. Then your mind will become quieter and quieter in any surroundings, like a still forest pool. All kinds of wonderful, rare animals will come and drink at the pool. You will see clearly the nature of all things in the world. Many wonderful strange things come and go, but you will be still. This is the happiness of the Buddha.