Almost everything about Patañjali is unknown. Even his most basic biographical details are disputed. And of the little that is known, much is mired in myth.

The dates proposed for Patañjali’s birth and life vary by a millennium. Some authorities suggest that he lived and flourished in the 4th century BCE, while others insist that he must have lived in the 6th century CE. A part of the reason for this wide divergence in possible dates is the tradition, common at the time (it existed also in contemporary Greek society and still causes endless problems for historians), to ascribe anything worth saying to someone already acknowledged as a great exponent. In order to make their contributions more acceptable, and to give them some cachet and an air of authority, later thinkers were frequently content to concede authorship of their contributions to one or another of their more illustrious predecessors. Those predecessors thus acquired an exaggerated longevity. In the face of the conflicting evidence the best that can now be done is to come up with a consensus for the most likely dates for Patañjali’s birth and death. Given that the knowledge in Patañjali’s most widely recognized work, the Yoga Sutras, is presented through a series of terse aphorisms, a date for him of somewhere between the fourth and second centuries BCE becomes highly likely. It was over that period that the aphorism style not only gained extensive acceptance, but reached probably its greatest stylistic peak. Patañjali’s work is widely regarded as the finest example extant of the sutra method of presentation. Give or take a century, therefore, somewhere around 250 BCE seems the best bet.

Trying to determine Patañjali’s parentage poses further problems. According to one legend he was the son of Angiras, one of the ten sons of Brahma, the Creator; and of Sati, the consort of Siva. If so, this would make him not only the grandson of the Creator of the universe, but also the brother of Brhaspati, god of wisdom and eloquence and chief offerer of sacrifices.

According to another legend, shortly before Patañjali was born the Lord Vishnu was seated on his serpent, Adisesa. (Adisesa is in fact one of the many incarnations of Vishnu). While seated on his serpent carriage Vishnu was enraptured by the dancing of Lord Siva. Vishnu was so affected that his body began to vibrate causing him to pound down heavily on Adisesa—who consequently suffered great discomfort. When the dance ended the weight was instantaneously lifted. Adisesa asked Vishnu what had happened. On hearing about the dance Adisesa wanted to learn it so he could personally dance it for the pleasure of Vishnu, his lord. Vishnu was impressed and predicted to Adisesa that one day Lord Siva would bless him for his understanding and devotion and that he would be incarnated so that he could both shower humanity with blessings and fulfill his own desire to master dance. Adisesa immediately began to ponder on the question of who his mother would be. At the same time a virtuous woman named Gonika, who was totally devoted to yoga, was praying and seeking for someone to be a worthy son to her. She wanted to pass on the knowledge and understanding she had gained through yoga. Concerned that, with her days on earth now severely numbered, she had not yet found a candidate, she prostrated herself before the Sun, the earthly manifestation of the light and presence of God. She scooped up the only gift she could find—a handful of water—and beseeched him to bestow her with a son. She then meditated upon the Sun and prepared herself to present her simple but sincere offering. On seeing all this Adisesa—the bearer of Vishnu—knew that he had found the mother he was looking for. Just as Gonika was about to offer her handful of water to the Sun, she glanced down at her hands and was astonished to see a tiny serpent moving in her hands. She was even more astonished when, within a few moments, that serpent had assumed a human form. Adisesa, who it was, in his turn prostrated before Gonika and pleaded with her to accept him as her son.

(2) His place of birth

As for where Patañjali was born—this, also, is far from clear. Nor is it clear exactly where he lived. Mount Meru stands at the centre of the universe … and is generally taken as an allegory for the human spine. It is surrounded by seven continents. The central one, which encircles Mount Meru, is called Jambudvipa after the Jambu (rose apple) trees that abound in it. One particular Jambu tree stands proudly atop Mount Meru. Its fruits and flowers are visible across the entire continent and are much desired by its inhabitants. Jambudvipa is divided into nine (some say seven) Varshas or regions separated from each other by mountain ranges. These nine are Bharata, Ilavrita, Hari, Kuru, Hiranmaya, Ramyaka, Ketumala, Bhadrasva and Kimnara. India proper is sometimes taken to be Jambudvipa itself; but it is more frequently taken to be Bharatavarsha. It is therefore where the descendants of Bharata and/or the bharatas live. The former is taken to be Agni, the god of fire and/or the author(s) of the Rig Veda; the latter are taken to be the priests who carry the oblations. Only in Bharatavarsha do the four yugas or ages (Krita, Treta, Dvapara and Kali) exist. Only Bharatavarsha, therefore, allows for a ‘proper’ passage of time and the due working out of karma. But while Bharata may be ‘ordinary’ in containing time, actions and consequences as we know them, it is nevertheless full of devotees who perform the necessary religious and spiritual austerities promptly, willingly and devotedly. This gives hope of salvation to all its inhabitants. So although Bharata (or Bharatavarsha) may be an ‘ordinary’ place, it is still ‘most excellent’. The other eight varshas contain various beings who are beyond time and karma and who thus do nothing more than enjoy the fruits of their current and previous existences.

Tradition holds that Sage Patañjali was not born in Bharatavarsha—i.e. in any ordinary place. He was rather born in Ilavritavarsha. Some insist that Ilavrita is not one of the divisions of Jambudvipa at all but an exalted place beyond. It is inhabited only by gods and those few spiritual beings who embody supreme spirituality and transcendence. Ilavrita, therefore, is not strictly a part of India, or any other earthly country, but an ethereal and celestial abode.

In order to appease those who always want to be literal, and who will settle for nothing less than verifiable facts, it is probably wisest to concede that all these tales of Patañjali’s birth and his likely domicile are most probably allegories. So it could be that what is being implied is that, in common with all those other great rishis and seers who have benefitted humanity, Patañjali came to these earthly times and places from some completely other sphere. He came to elucidate knowledge for the benefit of those dwellers in Bharata who—afflicted as they are by time, existence and the workings out of causes and effects—are still nevertheless eager to receive and imbibe it.

(3) His life

However and wherever he was born, Patañjali eventually appeared on earth to fulfill his self-appointed destiny. Unsurprisingly, given his lineage, he had no ordinary childhood. He could apparently communicate fully from the moment he was born. Not only that, but both the topics of his conversations and the intellect and vigour with which he discussed them were of the kind more usually associated with sages, rishis and seers. Patañjali not only acutely and accurately analysed and discussed things of the present, but revealed matters of both the ancient past and the immediate and distant futures with accuracy and incisive penetration. The cut and thrust of his eye, mind and mouth were of such intensity that on one occasion, when the inhabitants of Bhotabhandra chose to disturb him in the middle of his religious austerities and ridiculed him, he reduced them to ashes with nothing more than the fire of his mouth and speech. His marriage is also the stuff of legend. One day he seems to have discovered an exquisitely and enchantingly beautiful maiden, Lolupa, in the hollow of a tree on the north slope of Mount Sumeru—the top of the celestial mountain of enlightenment. He promptly married her, thus indissolubly joining himself to the fruits of his spiritual quest, and lived to a ripe and happy old age.

(4) His portrayal and iconography

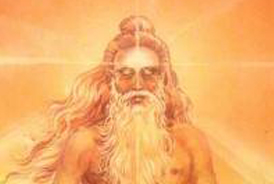

As portrayed in the photograph above, Lord Patañjali is reckoned to be an incarnation of the serpent Ananta, whose name means ‘the endless one’—and who is another form of Adisesa. He is therefore, on some accounts, Lord Vishnu’s seat, for Vishnu sits upon Adisesa before the beginning of creation.

Above Patañjali is the cobra’s hood, the sign of ultimate protection from all possible evils and difficulties in the world. There are seven serpent hoods forming a divine umbrella protecting both Patanjali and all aspirants who turn to him for guidance. Those seven hoods symblize his mastery and conquest of the five elements of earth, water, fire, air and ether, along with the attainment of moksha and samadhi, liberation and enlightenment.

Patañjali himself is generally depicted as half human and half serpent. His human torso emerges from the coils of the all-powerful serpent, who is awakening in the moment of creation. The serpent embodies that creative energy. It is coiled three and a half times. There is one coil each for the earth, the atmosphere and the heavens. Or, again, one coild each to represent his omnipresent, omnipotent and omniscient natures. And then a further half-coil to show that he sets aside the material nature, rises above them all, and is absorbed only in the world seen in meditation, being free from everything else.

Patañjali’s hands are in the traditional Indian greeting of ‘namaste’—sometimes called an ‘añjali’ or offering. Since ‘pata’ means fallen, ‘Patañjali’ can be roughly translated as ‘the grace (or “the grace-full one”) that falls from heaven’.

The lord is generally depicted in a meditative trance. His folded hands are both blessing and greeting those who have approached him seeking yoga and its truths. His salutation eases their labours with its grace. It also assures them that those labours will eventually bear fruit. Patañjali in fact has not two, but four hands. The two immediately in front of him create the blessings of the añjali while the other two are raised. One of the uplifted hands holds sankha, the conch that embodies the energy of sound. It both calls students to practice and announces the imminent ending of the world as they have so far known it. His other uplifted hand holds the cakra or discus that embodies both the turning wheel of time and its associated law of cause and effect.

(5) His achievements

When it comes to determining what Patañjali did, the uncertainties continue. A first achievement, which is not surprising given the tales of his parentage, is his recognition as a truly great dancer. To this day dancers in India working in the classical traditions invoke him and pay him their respects. Patañjali, therefore, is effectively the patron saint of dance.

Some say that Patañjali also wrote a treatise on ayurvedic medicine. Certainly, the texts in question focus on what could well have been Patañjali’s main interests: the diagnosis of disease; the structure and function of the human body; the problem of keeping the body fit, pleasing-feeling and good looking; and the curative values and properties of drugs and the techniques required to administer them. All these are mentioned in the Yoga Sutras. But although a strong tradition does insist that the Patañjali who wrote the ayurvedic text is the self-same Patañjali who wrote the Yoga Sutras, scholars do not accept this as an established fact. But an argument that can be made against these scholarly types is that they are rather missing the point. Svayambhus—divine beings who bring about their own causeless existences, who are without karma, and who manifest themselves as evolved and highly spiritual beings for the betterment of humanity—are in no way obliged to respect historical facts.

The waters are further muddied when it comes to another great treatise attributed to Patañjali.

It is (almost!) beyond dispute that a famous man named Patañjali was born in Gonarda and that he lived, for at least a little while, in Kashmir. This particular Patañjali lived and wrote in about (?!) 140 BCE. He was a great grammarian and hisMahabhashya or Great Commentary on Panini’s grammar (the first great grammar written for any language) was magisterial. It is still read and acknowledged today. But the Mahabhashya was a lot more than just a commentary. The Patañjali who wrote it took Panini’s work a great deal further. He redefined the rules of Sanskrit grammar. He greatly enlarged its vocabulary. He gave Sanskrit a muscular power that made it a more precise, subtle, effective and artistic instrument capable of expressing any aspect whatever of human thought or existence. Furthermore, this Patañjali did not just provide a body of theory. He demonstrated the possibilities of Sanskrit through his skills and artistry in its use.

Clearly, the question of the moment is whether the Patañjali who wrote the Mahabhashya was (a) the same as the Patañjali who wrote on ayurveda; and/or (b) the same as the Patañjali who wrote on yoga (never mind (c) the same as the one who was a founding father of dance).

Focusing on grammar and yoga, there is the inevitable initial problem of validating the necessary contemporaneous dates and locations. Although it is not conclusive, the best evidence is in the negative. The Patañjali of the Yoga Sutras surely lived several centuries before the Patañjali of the Mahabhashya. There is not (as) much leeway in the dates for the latter. Added to this is some internal evidence. Philosophical contradictions between the two texts would seem to indicate that they simply cannot have had the same author. This, however, is a far from convincing argument. It is easy enough, after all, to find writers who express contradictory ideas on the same page never mind in such different books, on such vastly different subjects, and written at different points in their lives. Furthermore, a work of grammar is a very different animal from a book on yoga. It is surely not to be wondered at, then, if ideas that show themselves to best advantage in the one field are not in any way efficacious—and, indeed, cause great difficulties—when carried over to another. The point is surely that both are excellent self-contained works with impeccable arguments and logical structures in their respective fields. This is surely exactly what they should be. It is true that it would be neat if it were otherwise but, at the end of the day, there is no reason why the one work is obliged to make reference to, or be 100% compatible with, the other.

All told, the tradition that conflates these three Patañjalis (four if dance is added to grammar, medicine and yoga) into one has been around some two millennia … and it is not about to die out any time soon.

(6) His contribution

Unfortunately, the confusion about Patañjali’s life permeates the very thing for which he is the most famous: the Yoga Sutras. There is uncertainty about (at least) three important things. Did Patañjali actually write the Yoga Sutras? If he did, did he make an original contribution or was he ‘merely’ a collator and systematizer? And assuming that the answer to the first question is affirmative, is the text we have today what Patañjali actually wrote?

Probably the greatest controversy concerns the fourth pada or chapter of the Yoga Sutras. Some commentators argue that its style and content are very different from the first three. For one thing, it is exceptionally short. This brevity would not amount to much if it were not for the structure of its argument. The first three chapters seem to develop their themes in a leisurely and non-dogmatic manner. The fourth, by contrast, seems much more rushed. It has the air of striving earnestly to make a point. Sutra 16 is probably the most controversial of all in that it seems to have been lifted from Vyasa’s seventh commentary. At one point Vyasa seems to be expounding on Patañjali and countering arguments raised by Buddhism. At another moment he seems to be saying that a particular sentence he is elucidating is in any case something Patañjali said. But—it is unclear if Patañjali actually said it, or if Vyasa merely says he did.

Another bone of contention is that, unlike the first two chapters, the third ends with ‘iti’. ‘Iti’ has the rough meaning of ‘thus as it was intended’ (somewhat like the QED or quod erat demonstrandum of mediaeval and Renaissance geometric texts). It is the traditional way of ending a Sanskrit text—meaning that there seem to be two ‘The End’s in one book. The critics declare that it is most curious that one book should contain two ‘iti’s or ‘The End’s.

Those who prefer to affirm the unity of the Yoga Sutras are unconvinced by the above arguments. They point out that the fourth chapter is physically and metaphysically coherent with the previous three and that the four, taken together, achieve a remarkable degree of homogeneity and thematic consistency. All the fourth chapter does is describe the same topic—but from the standpoint of one who has succeeded rather than one who is still seeking. The sceptics promptly counter by saying that anyone wanting to pass off an obviously later interpolation as a part of the original would have gone to exactly this kind of trouble. Clearly, it is important to settle whether the first three chapters, which both sides use as their measuring stick, are indisputable as Patañjali originals. Settling even this becomes difficult because the status of some sutras (with sutra 22 in Chapter III being probably the most famous example) has also been questioned. It, also, say the critics, seems to be a later interpolation in that it disturbs an otherwise smooth flow. The obvious response is then made. This authenticity debate is not one that can really be resolved.

As for what precise contribution Patañjali made, this is also hard to settle. Yoga, or some yoga-like subject, definitely existed before him. The oldest of the Upanishads make unequivocal references to, for example, pranayama, the science of the breath. The later Katha Upanishad, amongst half a dozen others of the same vintage, indicates that that era already enjoyed several different systems of yoga. This differentiation bespeaks a long ancestry. The more specifically yogic Upanishads, such as theHamsa, the Yogatattva, the Yogakundali and some half a dozen others, are later still and give instructions—admittedly obscure—for asanas and other yogic disciplines. Although yoga is ultimately about practice, it is also a philosophy and a metaphysic. Of the Upanishads, probably only the Maitrayana has a distinct leaning towards the Sankhya philosophy—something that is essential for the full emergence of yoga as a system of thought. Yoga is complementary to Sankhya. It has the goal of realizing the Spirit from within the world of nature as discussed in Sankhya. By the time of the Mahabharata—the great epic that is effectively the early history of India—both Sankhya and Yoga are being taken for granted as pre-existing and already ancient systems of thought. It is therefore appropriate that they have founders. Kapila has become the fountainhead for Sankhya while Hiranyagarbha fulfills a similar role for yoga. According to the Ahirbudhnya, Hiranyagarbha revealed the whole of yoga in the Nirodha Samhita and Karma Samhita. And … it is surely beyond coincidence that the second sutra of the Yoga Sutras defines yoga in terms of nirodha. Not only that, but the Nirodha Samhita is often called the Yoganushasanam … the very words with which Patañjali begins the Yoga Sutras. If Patañjali did make original contributions then he borrowed heavily from pre-existing trends in Sankhya and Yoga.

As to the question of originality, although Patañjali (at least, as evidenced in his Yoga Sutras) is clearly of the lineage of Hiranyagarbha and Kapila, he does differ from them in important respects. This could have been because he had genuinely had ideas of his own. But yoga was strongly associated with the shramana tradition, these being wandering forest mendicants and seekers. It therefore encouraged independence of thought. So Patañjali could just as well have been trying to bring order to a system with widely divergent methods. Some insist that ‘all’ he did was bring together and summarize a varied body of texts most of which have now been lost. Whatever was his inspiration, Patañjali does seem to have propounded many ideas that were not of the mainstream in either Sankhya or Yoga. He recognizes ego, for example, but does not accept it is a separate principle. He recognizes the subtle body but does not regard it as permanent. He also denies that it can operate directly on external things. These ideas differ from the mainstream, at that time, in both Sankhya and Yoga. Like all others concerning Patañjali the question of what is original with him is well nigh impossible to settle. The Yoga Sutras could easily have been his original thoughts on both Sankhya and Yoga. On the other hand, he could have been reinterpreting and clarifying what others had said, freeing them at the same time from contradictions. The very least that can be said is that he brought many threads, some dating back to the Vedas and Upanishads, together; and that he did so with what modern psychology would call genius. What had previously been long-winded and obscure he encapsulated in the nuggets of his sutras; and what had previously been abstract he made practical and easy to validate through the lives and experiences of a long line of teachers and practitioners. While the Yoga Sutras initially appears to be a dry and theoretical text, it explains human nature and psychology while also being an intensely practical manual for spiritual advancement.

Ultimately, the historical uncertainties concerning Patañjali are of little concern to those who wish to achieve some measure of success in the things of which he wrote: gaining inner tranquillity and attaining spiritual realization. Its authorship and genesis may be contested but the Yoga Sutras is a coherent and self-sustaining whole that supports the seeking aspirant on theoretical and practical levels. A part of the reason for its longevity and the high regard in which it is held is that Patañjali provided a framework capable of supporting the vastly different modes of comprehension and understanding that one person goes through over a lifetime; that many make over cultures; and that the human consciousness to which Patañjali spoke so eloquently makes over epochs.