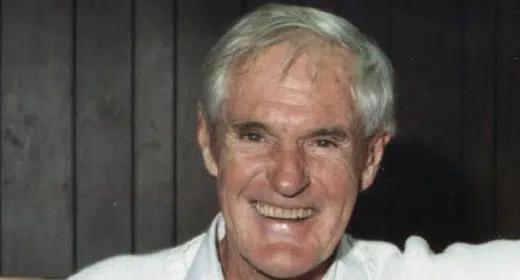

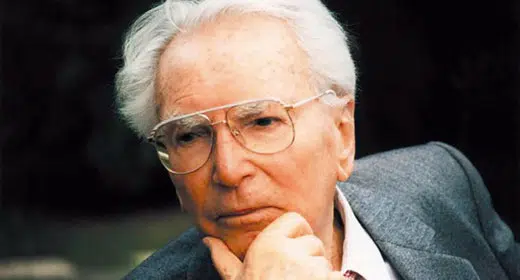

by Emily Davidow: Delighted to share an excerpt from an interview with Robert Thurman by a fellow traveler on our Journey with Robert Thurman in Bhutan expedition, David Bullard.  David is a San Francisco-based clinical psychologist, licensed marital and family therapist, and clinical professor of medicine and medical psychology (psychiatry) at the University of California, San Francisco. He offers a series of insightful interviews related to relationships, Buddhism and psychology at DrBullard.com.

David is a San Francisco-based clinical psychologist, licensed marital and family therapist, and clinical professor of medicine and medical psychology (psychiatry) at the University of California, San Francisco. He offers a series of insightful interviews related to relationships, Buddhism and psychology at DrBullard.com.

This interview took place at Menla Mountain Retreat, which also is known as The Land of the Healing Buddha, one of the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan medicine healing centers, on August 14, 2010, during a workshop with Dr. Thurman and psychiatrist/author Mark Epstein, M.D., “Integrating Buddhism and Psychotherapy.”

David Bullard: Hello Tenzin Bob! Thank you so much for making time for this interview! To begin, here is a copy of neuropsychologist Richard Hanson’s new book, Buddha’s Brain — which he wanted you to have. Let’s start with some observations from the book: We each have about 1.1 trillion brain cells and 100 billion neurons, each of which fires up to 50 times per second and can possibly can be connected to 5,000 other neurons. Hanson says, doing the math, if you think of all those possible combinations and permutations of connections of 100 billion neurons each possibly connected to 5,000 others, you end up with 10 to the one-millionth different brain state possibilities. In contrast, the number of atoms in the physical universe is 10 to the 80th.

Tenzin Bob Thurman: Whoa — fabulous! That proves one thing — that brain size is equivalent to the universe, the Buddha-verse size. And that proves that our notion of the size of the universe is wrong – the ten to the 80th, is completely wrong. And just because they don’t see further and they think everything is running away – all the stars are red-shifting away – that’s just a mistake.

Beyond that is a barrier of darkness they think they can’t see beyond, so you can’t see all those millions of other universes. So you know the universe surely is the size of the brain, at least. The two are interconnected I’m sure, and the universe is in the brain. They are all interwoven – the Jewel Net of Indra they call it – the interpenetration of all things.

Anyway, that’s certainly the Cosmic Vision. We shouldn’t feel like we’re restricted to one miserable little universe that is only 10 to the 80th power!

DB: Here’s something I’ve been wondering about: can you talk a bit about the difference between a guru in some spiritual traditions and a “spiritual friend” in the Tibetan tradition?

TBT: In most levels of Buddhism the authority and projection level of the mentor or teacher is de-emphasized because the burden is on the students to find things out for themselves, so the basic model of the spiritual teacher is that of a virtuous friend or auspicious friend, one who brings you good luck, and by giving teachings helps you gain knowledge and experience.

As a friend, he or she helps you on your way but you have to do it. It is important to remember the patriarchal context of Indian society. In traditional Indian knowledge fields the guru is a big authority figure – like a father figure – while there is a de-emphasizing of the father figure in most levels of Buddhism. In monastic Buddhism, the abbot is not a big boss, and obedience is not a big virtue for the Buddhist monk or mendicant. In the Mahayana tradition, the spiritual friend is a teacher emphasizing how you have to get out there and do your own bodhisattva deeds and become a Buddha.

But in the Tantric and esoteric teachings, the guru figure – which in Tibetan is translated as the “Lama” – is brought back into play because in Tantra you’re dealing with the unconscious and you need someone upon whom to project different things to help you work out new relationships, like you do in psychotherapy. Also, there’s the initiatory practice of seeing the guru as the living embodiment of the Buddha when the teachings are transmitted to you.

The Tibetans have a proverb: “The best guru is one who lives at least three valleys away,” which means you receive the teaching and some initiatory consecration – and then you don’t hang out with that person to see how ordinary they are!

DB: Kierkegaard said this: “Perfect love means to love the one through whom one became unhappy.”

TBT: “…through whom one became unhappy?” That’s perfect love? Sure… That means “love thine enemy!” as Jesus recommended. For the enemy harms one, and that can make one unhappy. But if one has perfect love, one will want especially that enemy to be happy anyway.

Whether or not one becomes unhappy at first when harmed, perfect love surely does mean complete and unflagging desire for the happiness of the beloved as the Buddha defined it, and that usually doesn’t make one unhappy, even if it’s unrequited. If it’s perfect love then one is happy just in the loving and in seeing and wishing and hoping for the happiness of the beloved. That brings happiness to the one.

The Dalai Lama likes to say, “If you want to be successfully selfish, which means you want to be happy yourself, at least be wisely selfish, which means be unselfish, because being unselfish is what makes yourself happy and therefore fulfills your selfish interests.” It’s very paradoxical. Everything in life is very paradoxical, and that’s one of the most wonderful paradoxes in life.

So Kierkegaard was a Dane and lived in a time of very uptight Scandinavian society – which all Scandinavians can testify to – with the valley of tears, the veil of suffering and sorrow. So naturally, he might feel someone could or would make you unhappy by being your enemy, and he could see that love would need to be perfect to extend itself even to that enemy!

…

In Buddhism, perfect love means Maitreya Buddha, you know; maitreya means love… the loving Buddha… perfect love… The person who loves perfectly is always going to be happy. No matter what happens to that person, that person will be happy.

DB: I’m feeling perfectly happy and loving this discussion, Bob! But I’m going to close with one more quote: This one is from the renowned Canadian novelist and poet Margaret Atwood that goes back to your suggestions about positive psychology and increasing our capacity for growth. She said “the Eskimos have 52 names for snow because it was important to them: there ought to be as many for love.”

TBT: That’s very true… I think that’s absolutely true…

DB: …and you’ve spoken of the many aspects of Tibetan Buddhism that speak deeply of love and relationships.

TBT: There’s a wonderful passage in the Vimalakirti Sutra where he talks about the love of the bodhisattva and the love of the Buddha. To have perfect love, you actually have to be perfectly happy yourself. You have to be happy, since love is what wills the happiness of the beloved. If you don’t know yourself what happiness is, then how can you really be willing their happiness? You may be willing them to do something that you think might make them happy, but that won’t necessarily be what does make them happy.

When you yourself have a kind of reliable type of inner bliss awareness, a sense of connectedness to the universe where you feel the bliss of life flowing up and bubbling up within you, the bliss of freedom coming up within you, then you want others to have that. And that naturally overflows in the love that wants the beloved to be happy, because you realize happiness is everyone’s birthright.

If you are really blissed-out like a Buddha, you see the bliss in the cells of the beloved and you realize it’s trapped from their own experience by some notion that they have: that bliss is not theirs, that they don’t have it, or someone is chasing them, and they live in fear. So your whole drive becomes to try to help them remove the blinders that have been placed on them by their experience, by their fear, by their culture, whatever notions they have that they are not allowed to be happy, not allowed to feel unreasoned and unreasonable bliss, and you then would do whatever it takes to free them.

It doesn’t mean you would stare at them or smile at them or behave weirdly with them because that might freak them out even more. For a paranoiac – you can’t give him a hug or he’ll think you’re trying to smother him – you have to do a different kind of dance for a different type of person. But the person who is moved by bliss toward perfect love will come up with an effective dance, like mothers do with children. They will figure out that they’re hungry and what they need. For a mother who loves her child, that love will provide her with the intelligence and the skill to find out how to stop the problem.