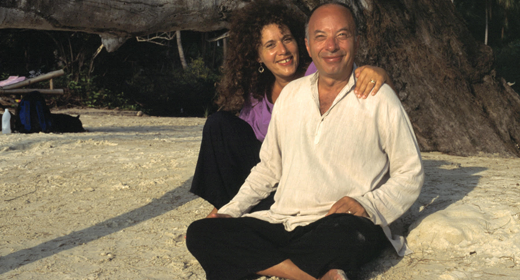

It’s hard to always show compassion — even to the people we love, but Robert Thurman asks that we develop compassion for our enemies. Pt 2

He prescribes a seven-step meditation exercise to extend compassion beyond our inner circle.

Transcript: I want to open by quoting Einstein’s wonderful statement, just so people will feel at ease that the great scientist of the 20th century also agrees with us, and also calls us to this action. He said, “A human being is a part of the whole, called by us, the ‘universe,’ — a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion, to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

This insight of Einstein’s is uncannily close to that of Buddhist psychology, wherein compassion — “karuna,” it is called — is defined as, “the sensitivity to another’s suffering and the corresponding will to free the other from that suffering.” It pairs closely with love, which is the will for the other to be happy, which requires, of course, that one feels some happiness oneself and wishes to share it. This is perfect in that it clearly opposes self-centeredness and selfishness to compassion, the concern for others, and, further, it indicates that those caught in the cycle of self-concern suffer helplessly, while the compassionate are more free and, implicitly, more happy.

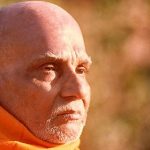

The Dalai Lama often states that compassion is his best friend. It helps him when he is overwhelmed with grief and despair. Compassion helps him turn away from the feeling of his suffering as the most absolute, most terrible suffering anyone has ever had and broadens his awareness of the sufferings of others, even of the perpetrators of his misery and the whole mass of beings. In fact, suffering is so huge and enormous, his own becomes less and less monumental. And he begins to move beyond his self-concern into the broader concern for others. And this immediately cheers him up, as his courage is stimulated to rise to the occasion. Thus, he uses his own suffering as a doorway to widening his circle of compassion. He is a very good colleague of Einstein’s, we must say.

Now, I want to tell a story, which is a very famous story in the Indian and Buddhist tradition, of the great Saint Asanga who was a contemporary of Augustine in the West and was sort of like the Buddhist Augustine. And Asanga lived 800 years after the Buddha’s time. And he was discontented with the state of people’s practice of the Buddhist religion in India at that time.

Check out Good Medicine: How to Turn Pain Into Compassion with Tonglen Meditation, by Pema Chodron

And so he said, “I’m sick of all this. Nobody’s really living the doctrine. They’re talking about love and compassion and wisdom and enlightenment, but they are acting selfish and pathetic. So, Buddha’s teaching has lost its momentum. I know the next Buddha will come a few thousand years from now, but exists currently in a certain heaven” — that’s Maitreya — “so, I’m going to go on a retreat and I’m going to meditate and pray until the Buddha Maitreya reveals himself to me, and gives me a teaching or something to revive the practice of compassion in the world today.”

So he went on this retreat. And he meditated for three years and he did not see the future Buddha Maitreya. And he left in disgust. And as he was leaving, he saw a man — a funny little man sitting sort of part way down the mountain. And he had a lump of iron. And he was rubbing it with a cloth. And he became interested in that. He said, “Well what are you doing?” And the man said, “I’m making a needle.” And he said, “That’s ridiculous. You can’t make a needle by rubbing a lump of iron with a cloth.” And the man said, “Really?” And he showed him a dish full of needles. So he said, “Okay, I get the point.” He went back to his cave. He meditated again.

Another three years, no vision. He leaves again. This time, he comes down. And as he’s leaving, he sees a bird making a nest on a cliff ledge. And where it’s landing to bring the twigs to the cliff, its feathers brushes the rock — and it had cut the rock six to eight inches in. There was a cleft in the rock by the brushing of the feathers of generations of the birds. So he said, “All right. I get the point.” He went back.

Another three years. Again, no vision of Maitreya after nine years. And he again leaves, and this time: water dripping, making a giant bowl in the rock where it drips in a stream. And so, again, he goes back. And after 12 years there is still no vision. And he’s freaked out. And he won’t even look left or right to see any encouraging vision.

And he comes to the town. He’s a broken person. And there, in the town, he’s approached by a dog who comes like this — one of these terrible dogs you can see in some poor countries, even in America, I think, in some areas — and he’s looking just terrible. And he becomes interested in this dog because it’s so pathetic, and it’s trying to attract his attention. And he sits down looking at the dog. And the dog’s whole hindquarters are a complete open sore. Some of it is like gangrenous, and there are maggots in the flesh. And it’s terrible. He thinks, “What can I do to fix up this dog? Well, at least I can clean this wound and wash it.”

So, he takes it to some water. He’s about to clean, but then his awareness focuses on the maggots. And he sees the maggots, and the maggots are kind of looking a little cute. And they’re maggoting happily in the dog’s hindquarters there. “Well, if I clean the dog, I’ll kill the maggots. So how can that be? That’s it. I’m a useless person and there’s no Buddha, no Maitreya, and everything is all hopeless. And now I’m going to kill the maggots?”

So, he had a brilliant idea. And he took a shard of something, and cut a piece of flesh from his thigh, and he placed it on ground. He was not really thinking too carefully about the ASPCA. He was just immediately caught with the situation. So he thought, “I will take the maggots and put them on this piece of flesh, then clean the dog’s wounds, and then I’ll figure out what to do with the maggots.”

So he starts to do that. He can’t grab the maggots. Apparently they wriggle around. They’re kind of hard to grab, these maggots. So he says, “Well, I’ll put my tongue on the dog’s flesh. And then the maggots will jump on my warmer tongue” — the dog is kind of used up — “and then I’ll spit them one by one down on the thing.” So he goes down, and he’s sticking his tongue out like this. And he had to close his eyes, it’s so disgusting, and the smell and everything.

And then, suddenly, there’s a pfft, a noise like that. He jumps back and there, of course, is the future Buddha Maitreya in a beautiful vision — rainbow lights, golden, jeweled, a plasma body, an exquisite mystic vision — that he sees. And he says, “Oh.” He bows. But, being human, he’s immediately thinking of his next complaint.

So as he comes up from his first bow he says, “My Lord, I’m so happy to see you, but where have you been for 12 years? What is this?”

And Maitreya says, “I was with you. Who do you think was making needles and making nests and dripping on rocks for you, mister dense?” (Laughter) “Looking for the Buddha in person,” he said. And he said, “You didn’t have, until this moment, real compassion. And, until you have real compassion, you cannot recognize love.” “Maitreya” means love, “the loving one,” in Sanskrit.