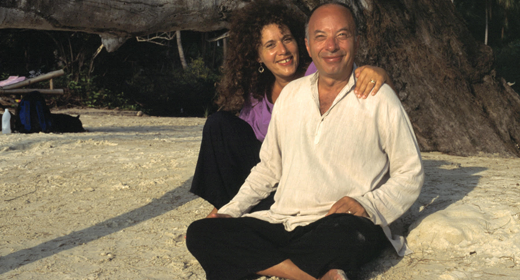

by Jack Kornfield: Just as we open and heal the body by sensing its rhythms and touching it with a deep and kind attention, so we can open and heal other dimensions of our being…

The heart and the feelings go through a similar process of healing through the offering of our attention to their rhythms, nature, and needs. Most often, opening the heart begins by opening to a lifetime’s accumulation of unacknowledged sorrow, both our personal sorrows and the universal sorrows of warfare, hunger, old age, illness, and death. At times we may experience this sorrow physically, as contractions and barriers around our heart, but more often we feel the depth of our wounds, our abandonment, our pain, as unshed tears. The Buddhists describe this as an ocean of human tears larger than the four great oceans.

As we take the one seat and develop a meditative attention, the heart presents itself naturally for healing. The grief we have carried for so long, from pains and dashed expectations and hopes, arises. We grieve for our past traumas and present fears, for all of the feelings we never dared experience consciously. Whatever shame or unworthiness we have within us arises—much of our early childhood and family pain, the mother and father wounds we hold, the isolation, any past abuse, physical or sexual, are all stored in the heart. Jack Engler, a Buddhist teacher and psychologist at Harvard University, has described meditation practice as primarily a practice of grieving and of letting go. At most of the spiritual retreats I have been a part of, nearly half of the students are working with some level of grief: denial, anger, loss, or sorrow. Out of this grief work comes a deep renewal.

Many of us are taught that we shouldn’t be affected by grief and loss, but no one is exempt. One of the most experienced hospice directors in the country was surprised when he came to a retreat and grieved for his mother who had died the year before. “This grief,” he said, “is different from all the others I work with. It’s my mother.” Oscar Wilde wrote, “Hearts are meant to be broken.” As we heal through meditation, our hearts break open to feel fully. Powerful feelings, deep unspoken parts of ourselves arise, and our task in meditation is first to let them move through us, then to recognize them and allow them to sing their songs. A poem by Wendell Berry illustrates this beautifully.

I go among trees and sit still.

All my stirring becomes quiet

around me like circles on water.

My tasks lie in their places

Where I left them, asleep like cattle …

Then what I am afraid of comes.

I live for a while in its sight.

What I fear in it leaves it,

And the fear of it leaves me.

It sings, and I hear its song.

What we find as we listen to the songs of our rage or fear, loneliness or longing, is that they do not stay forever. Rage turns into sorrow; sorrow turns into tears; tears may fall for a long time, but then the sun comes out. A memory of old loss sings to us; our body shakes and relives the moment of loss; then the armoring around that loss gradually softens; and in the midst of the song of tremendous grieving, the pain of that loss finally finds release.

In truly listening to our most painful songs, we can learn the divine art of forgiveness. While there is a whole systematic practice of forgiveness that can be cultivated, both forgiveness and compassion arise spontaneously with the opening of the heart. Somehow, in feeling our own pain and sorrow, our own ocean of tears, we come to know that ours is a shared pain and that the mystery and beauty and pain of life cannot be separated. This universal pain, too, is part of our connection with one another, and in the face of it we cannot withhold our love any longer.

We can learn to forgive others, ourselves, and life for its physical pain. We can learn to open our heart to all of it, to the pain, to the pleasures we have feared. In this, we discover a remarkable truth: Much of spiritual life is self-acceptance, maybe all of it. Indeed, in accepting the songs of our life, we can begin to create for ourselves a much deeper and greater identity in which our heart holds all within a space of boundless compassion.

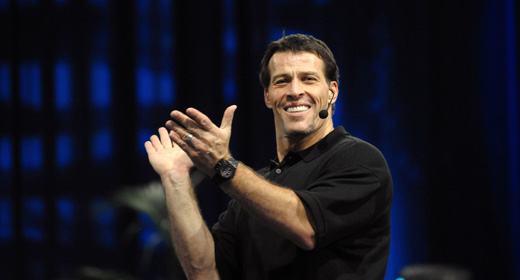

Most often this healing work is so difficult we need another person as an ally, a guide to hold our hand and inspire our courage as we go through it. Then miracles happen.

Naomi Remen, a physician who uses art, meditation, and other spiritual practices in the healing of cancer patients, told me a moving story that illustrates the process of healing the heart, which accompanies a healing of the body. She described a young man who was twenty-four years old when he came to her after one of his legs had been amputated at the hip in order to save his life from bone cancer. When she began her work with him, he had a great sense of injustice and a hatred for all “healthy” people. It seemed bitterly unfair to him that he had suffered this terrible loss so early in his life. His grief and rage were so great that it took several years of continuous work for him to begin to come out of himself and to heal. He had to heal not simply his body, but also his broken heart and wounded spirit.

He worked hard and deeply, telling his story, painting it, meditating, bringing his entire life into awareness. As he slowly healed, he developed a profound compassion for others in similar situations. He began to visit people in the hospital who had also suffered severe physical losses. On one occasion, he told his physician, he visited a young singer who was so depressed about the loss of her breasts that she would not even look at him. The nurses had the radio playing, probably hoping to cheer her up. It was a hot day, and the young man had come in running shorts. Finally, desperate to get her attention, he unstrapped his artificial leg and began dancing around the room on his one leg, snapping his fingers to the music. She looked at him in amazement, and then she burst out laughing and said, “Man, if you can dance, I can sing.”

When this young man first began working with drawing, he made a crayon sketch of his own body in the form of a vase with a deep black crack running through it. He redrew the crack over and over and over, grinding his teeth with rage. Several years later, to encourage him to complete his process, my friend showed him his early pictures again. He saw the vase and said, “Oh, this one isn’t finished.” When she suggested that he finish it then, he did. He ran his finger along the crack, saying, “You see here, this is where the light comes through.” With a yellow crayon, he drew light streaming through the crack into the body of the vase and said, “Our hearts can grow strong at the broken places.”

This young man’s story profoundly illustrates the way in which sorrow or a wound can heal, allowing us to grow into our fullest, most compassionate identity, our greatness of heart. When we truly come to terms with sorrow, a great and unshakable joy is born in our heart.