by Pema Chödrön: Times of chaos and challenge can be the most spiritually powerful…

if we are brave enough to rest in their space of uncertainty. Pema Chödrön describes three ways to use our problems as the path to awakening and joy: go to the places that scare you, use poison as medicine, and regard what arises as awakened energy.Sometimes late at night or on a long walk with a friend, we find ourselves discussing our ideas about how to live and how to act and what is important in life. If we’re studying Buddhism and practicing meditation, we might talk of no-self and emptiness, of patience and generosity, of loving-kindness and compassion. We might have just read something or heard some teachings that turned our usual way of seeing things upside down. We feel that we’ve just reconnected with a truth we’ve always known and that if we could just learn more about it, our life would be delightful and rich.

We tell our friends of our longing to shed the huge burden we feel we’ve always carried. We suddenly are excited and feel it’s possible. We tell our friend of our inspiration and how it opens up our life. “It is possible,” we say, “to enjoy the very same things that usually get us down. We can delight in our job, delight in riding the subway, delight in shoveling snow and paying bills and washing dishes.”

You may have noticed, however, that there is frequently an irritating, if not depressing, discrepancy between our ideas and good intentions and how we act when we are confronted with the nitty-gritty details of real life situations.

One afternoon I was riding a bus in San Francisco, reading a very touching article on human suffering and helping others. The idea of being generous and extending myself to those in need became so poignant that I started to cry. People were looking at me as the tears ran down my cheeks. I felt a great tenderness toward everyone, and a commitment to benefit others arose in me. As soon as I got home, feeling pretty exhausted after working all day, the phone rang, and it was someone asking if I could please help her out by taking her position as a meditation leader that night. I said, “No, sorry, I need to rest,” and hung up.

It’s not a matter of the right choice or the wrong choice, but simply that we are often presented with a dilemma about bringing together the inspiration of the teachings with what they mean to us on the spot. There is a perplexing tension between our aspirations and the reality of feeling tired, hungry, stressed-out, afraid, bored, angry, or whatever we experience in any given moment of our life.

Naropa, an eleventh-century Indian yogi, one day unexpectedly met an old hag on the street. She apparently knew he was one of the greatest Buddhist scholars in India and asked him if he understood the words of the large book he was holding. He said he did, and she laughed and danced with glee. Then she asked him if he understood the meaning of the teachings in that book. Thinking to please her even more, he again said yes. At that point she became enraged, yelling at him that he was a hypocrite and a liar. That encounter changed Naropa’s life. He knew she had his number; truthfully, he only understood the words and not the profound inner meaning of all the teachings he could expound so brilliantly.

How do we work with our resentment when our boss walks into the room and yells at us? How do we reconcile that frustration and humiliation with our longing to be open and compassionate and not to harm ourselves or others? How do we mix our intention to be alert and gentle in meditation with the reality that we sit down and immediately fall asleep?

This is where we also, to one degree or another, find ourselves. We can kid ourselves for a while that we understand meditation and the teachings, but at some point we have to face it. None of what we’ve learned seems very relevant when our lover leaves us, when our child has a tantrum in the supermarket, when we’re insulted by our colleague. How do we work with our resentment when our boss walks into the room and yells at us? How do we reconcile that frustration and humiliation with our longing to be open and compassionate and not to harm ourselves or others? How do we mix our intention to be alert and gentle in meditation with the reality that we sit down and immediately fall asleep? What about when we sit down and spend the entire time thinking about how we crave someone or something we saw on the way to the meditation hall? Or we sit down and squirm the whole morning because our knees hurt and our back hurts and we’re bored and fed up? Instead of calm, wakeful, and egoless, we find ourselves getting more edgy, irritable, and solid.

This is an interesting place to find oneself. For the practitioner, this is an exceedingly important place.

When Naropa, seeking the meaning behind the words, set out to find a teacher, he continually found himself in this position of being squeezed. Intellectually he knew all about compassion, but when he came upon a filthy, lice-infested dog, he looked away. In the same vein, he knew all about nonattachment and not judging, but when his teacher asked him to do something he disapproved of, he refused.

We continually find ourselves in that squeeze. It’s a place where we look for alternatives to just being there. It’s an uncomfortable, embarrassing place, and it’s often the place where people like ourselves give up. We liked meditation and the teachings when we felt inspired and in touch with ourselves and on the right path. But what about when it begins to feel like a burden, like we made the wrong choice and it’s not living up to our expectations at all? The people we are meeting are not all that sane. In fact, they seem pretty confused. The way the place is run is not up to par. Even the teacher is questionable.

This place of the squeeze is the very point in our meditation and in our lives where we can really learn something. The point where we are not able to take it or leave it, where we are caught between a rock and a hard place, caught with both the upliftedness of our ideas and the rawness of what’s happening in front of our eyes—that is indeed a very fruitful place.

Instead of taking what’s occurred as a statement of personal weakness or someone else’s power, instead of feeling we are stupid or someone else is unkind, we could drop all the complaints about ourselves and others.

When we feel squeezed, there’s a tendency for mind to become small. We feel miserable, like a victim, like a pathetic, hopeless case. Yet believe it or not, at that moment of hassle or bewilderment or embarrassment, our minds could become bigger. Instead of taking what’s occurred as a statement of personal weakness or someone else’s power, instead of feeling we are stupid or someone else is unkind, we could drop all the complaints about ourselves and others. We could be there, feeling off guard, not knowing what to do, just hanging out there with the raw and tender energy of the moment. This is the place where we begin to learn the meaning behind the concepts and the words.

We’re so used to running from discomfort, and we’re so predictable. If we don’t like it, we strike out at someone or beat up on ourselves. We want to have security and certainty of some kind when actually we have no ground to stand on at all.

The next time there’s no ground to stand on, don’t consider it an obstacle. Consider it a remarkable stroke of luck. We have no ground to stand on, and at the same time it could soften us and inspire us. Finally, after all these years, we could truly grow up. As Trungpa Rinpoche once said, the best mantra is “OM—grow up—svaha.”

We are given changes all the time. We can either cling to security, or we can let ourselves feel exposed, as if we had just been born, as if we had just popped out into the brightness of life and were completely naked.

Maybe that sounds too uncomfortable or frightening, but on the other hand, it’s our chance to realize that this mundane world is all there is, and we could see it with new eyes and at long last wake up from our ancient sleep of preconceptions.

The truth, said an ancient Chinese master, is neither like this nor like that. It is like a dog yearning over a bowl of burning oil. He can’t leave it, because it is too desirable and he can’t lick it, because it is too hot.

So how do we relate to that squeeze? Somehow, someone finally needs to encourage us to be inquisitive about this unknown territory and about the unanswerable question of what’s going to happen next.

Right there in the uncertainty of everyday chaos is our own wisdom mind.

The state of nowness is available in that moment of squeeze. In that awkward, ambiguous moment is our own wisdom mind. Right there in the uncertainty of everyday chaos is our own wisdom mind.

We need encouragement to experiment and try this kind of thing. It’s quite daring, and maybe we feel we aren’t up to it. But that’s the point. Right there in that inadequate, restless feeling is our wisdom mind. We can simply experiment. There’s absolutely nothing to lose. We could experiment with not getting tossed around by right and wrong and with learning to relax with groundlessness.

When I was a child, I had a picture book called Lives of the Saints. It was filled with stories of men and women who had never had an angry or mean thought and had never hurt a fly. I found the book totally useless as a guide for how we humans were supposed to live a good life. For me, The Life of Milarepa, the great Tibetan yogi and poet, is a lot more instructive. Over the years, as I read and reread Milarepa’s story, I find myself getting advice for where I am stuck and can’t seem to move forward.

To begin with, Milarepa was a murderer, and like most of us when we blow it, he wanted to atone for his errors. And like most of us, in the process of seeking liberation, he frequently fell flat on his face. He lied and stole to get what he wanted, he got so depressed he was suicidal, and he experienced nostalgia for the good old days. Like most of us, he had one person in his life who continually tested him and blew his saintly cover. Even when almost everyone regarded him as one of Tibet’s most holy men, his vindictive old aunt continued to beat him with sticks and call him names, and he continued to have to figure out what to do with that kind of humiliating squeeze.

One can be grateful that a long lineage of teachers has worked with holding their seats with the big squeeze. They were tested and failed and still kept exploring how to just stay there, not seeking solid ground. They trained again and again throughout their lives not to give up on themselves and not to run away when the bottom fell out of their concepts and their noble ideals.

From their own experience they have passed along to us the encouragement not to jump over the big squeeze, but to look at it just as it is, not just out of the corner of an eye. They showed us how to experience it fully, not as good or bad, but simply as unconditioned and ordinary.

How do we learn to relate with what seems to stand between us and the happiness we deserve?

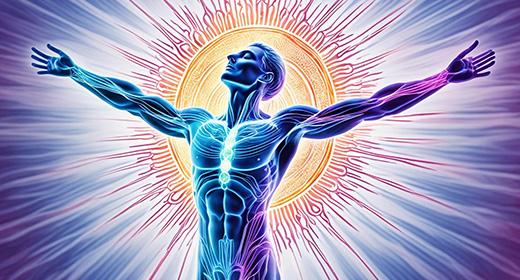

Through meditation practice, we realize that we don’t have to obscure the joy and openness that is present in every moment of our existence. We can awaken to basic goodness, our birthright. When we are able to do this, we no longer feel burdened by depression, worry, or resentment. Life feels spacious, like the sky and the sea. There’s room to relax and breathe and swim, to swim so far out that we no longer have the reference point of the shore.

How do we work with a sense of burden? How do we learn to relate with what seems to stand between us and the happiness we deserve? How do we learn to relax and connect with fundamental joy?

Times are difficult globally; awakening is no longer a luxury or an ideal. It’s becoming critical. We don’t need to add more depression, more discouragement, or more anger to what’s already here. It’s becoming essential that we learn how to relate sanely with difficult times. The earth seems to be beseeching us to connect with joy and discover our innermost essence. This is the best way that we can benefit others.

There are three traditional methods for relating directly with difficult circumstances as a path of awakening and joy. The first method we’ll call no more struggle; the second, using poison as medicine; and the third, seeing whatever arises as enlightened wisdom. These are three techniques for working with chaos, difficulties, and unwanted events in our daily lives.

Go to the Places that Scare You

The first method, no more struggle, is epitomized by shamatha-vipashyana (insight-awareness) meditation instruction. When we sit down to meditate, whatever arises in our minds we look at directly, call it “thinking,” and go back to the simplicity and immediacy of the breath. Again and again, we return to pristine awareness free from concepts. Meditation practice is how we stop fighting with ourselves, how we stop struggling with circumstances, emotions or moods. This basic instruction is a tool that we can use to train in our practice and in our lives. Whatever arises, we can look at it with a nonjudgmental attitude.

This instruction applies to working with unpleasantness in its myriad guises. Whatever or whoever arises, train again and again in looking at it and seeing it for what it is without calling it names, without hurling rocks, without averting your eyes. Let all those stories go. The innermost essence of mind is without bias. Things arise and things dissolve forever and ever. That’s just the way it is.

This is the primary method for working with painful situations—global pain, domestic pain, any pain at all. We can stop struggling with what occurs and see its true face without calling it the enemy. It helps to remember that our practice is not about accomplishing anything—not about winning or losing—but about ceasing to struggle and relaxing as it is. That is what we are doing when we sit down to meditate. That attitude spreads into the rest of our lives.

Approach what you find repulsive, help the ones you think you cannot help, and go to places that scare you.

It’s like inviting what scares us to introduce itself and hang around for a while. As Milarepa sang to the monsters he found in his cave, “It is wonderful you demons came today. You must come again tomorrow. From time to time, we should converse.” We start by working with the monsters in our mind. Then we develop the wisdom and compassion to communicate sanely with the threats and fears of our daily life.

The Tibetan yogini Machig Labdron was one who fearlessly trained with this view. She said that in her tradition they did not exorcise demons. They treated them with compassion. The advice she was given by her teacher and passed on to her students was, “Approach what you find repulsive, help the ones you think you cannot help, and go to places that scare you.” This begins when we sit down to meditate and practice not struggling with our own mind.

Use Poison as Medicine

The second method of working with chaos is using poison as medicine. We can use difficult situations—poison—as fuel for waking up. In general, this idea is introduced to us with the tonglen meditation practice of taking in pain and sending out positive energy.

When anything difficult arises—any kind of conflict, any notion of unworthiness, anything that feels distasteful, embarrassing, or painful—instead of trying to get rid of it, we breathe it in. The three poisons are passion (this includes craving or addiction), aggression, and ignorance (which includes denial or the tendency to shut down and close out). We would usually think of these poisons as something bad, something to be avoided. But that isn’t the attitude here; instead, they become seeds of compassion and openness. When suffering arises, the tonglen instruction is to let the story line go and breathe it in—not just the anger, resentment or loneliness that we might be feeling, but the identical pain of others who in this very moment are also feeling rage, bitterness, or isolation.

We breathe it in for everybody. This poison is not just our personal misfortune, our fault, our blemish, our shame—it’s part of the human condition. It’s our kinship with all living things, the material we need in order to understand what it’s like to stand in another person’s shoes. Instead of pushing it away or running from it, we breathe in and connect with it fully. We do this with the wish that all of us could be free of suffering. Then we breathe out, sending out a sense of big space, a sense of ventilation or freshness. We do this with the wish that all of us could relax and experience the innermost essence of our mind.

The main point of these methods is to dissolve the dualistic struggle, our habitual tendency to struggle against what’s happening to us or in us.

We are told from childhood that something is wrong with us, with the world, and with everything that comes along: it’s not perfect, it has rough edges, it has a bitter taste, it’s too loud, too soft, too sharp, too wishy-washy. We cultivate a sense of trying to make things better because something is bad here, something is a mistake here, something is a problem here. The main point of these methods is to dissolve the dualistic struggle, our habitual tendency to struggle against what’s happening to us or in us. These methods instruct us to move toward difficulties rather than backing away. We don’t get this kind of encouragement very often.

Everything that occurs is not only usable and workable but is actually the path itself. We can use everything that happens to us as the means for waking up. We can use everything that occurs—whether it’s our conflicting emotions and thoughts or our seemingly outer situation—to show us where we are asleep and how we can wake up completely, utterly, without reservations.

So the second method is to use poison as medicine, to use difficult situations to awaken our genuine caring for other people who, just like us, often find themselves in pain. As one lojong slogan says, “When the world is filled with evil, all mishaps, all difficulties, should be transformed into the path of enlightenment.” That’s the notion engendered here.

Regard What Arises as Awakened Energy

The third method for working with chaos is to regard whatever arises as the manifestation of awakened energy. We can regard ourselves as already awake; we can regard our world as already sacred.

Traditionally the image used for regarding whatever arises as the very energy of wisdom is the charnel ground. In Tibet the charnel grounds were what we call graveyards, but they weren’t quite as pretty as our graveyards. The bodies were not under a nice smooth lawn with little white stones carved with angels and pretty words. In Tibet the ground was frozen, so the bodies were chopped up after people died and taken to the charnel grounds, where the vultures would eat them. I’m sure the charnel grounds didn’t smell very good and were alarming to see. There were eyeballs and hair and bones and other body parts all over the place. In a book about Tibet, I saw a photograph in which people were bringing a body to the charnel ground. There was a circle of vultures that looked to be about the size of two-year-old children—all just sitting there waiting for this body to arrive.

Perhaps the closest thing to a charnel ground in our world is not a graveyard but a hospital emergency room. That could be the image for our working basis, which is grounded in some honesty about how the human realm functions. It smells, it bleeds, it is full of unpredictability, but at the same time, it is self-radiant wisdom, good food, that which nourishes us, that which is beneficial and pure.

Regarding what arises as awakened energy reverses our fundamental habitual pattern of trying to avoid conflict, trying to make ourselves better than we are, trying to smooth things out and pretty them up, trying to prove that pain is a mistake and would not exist in our lives if only we did all the right things. This view turns that particular pattern completely around, encouraging us to become interested in looking at the charnel ground of our lives as the working basis for attaining enlightenment.

Often in our daily lives we panic. We feel heart palpitations and stomach rumblings because we are arguing with someone or because we had a beautiful plan and it’s not working out. How do we walk into those dramas? How do we deal with those demons, which are basically our hopes and fears? How do we stop struggling against ourselves? Machig Labdron advises that we go to places that scare us. But how do we do that?

We can dissolve the sense of dualism between us and them, between this and that, between here and there, by moving toward what we find difficult and wish to push away.

We’re trying to learn not to split ourselves between our “good side” and our “bad side,” between our “pure side” and our “impure side.” The elemental struggle is with our feeling of being wrong, with our guilt and shame at what we are. That’s what we have to befriend. The point is that we can dissolve the sense of dualism between us and them, between this and that, between here and there, by moving toward what we find difficult and wish to push away.

In terms of everyday experience, these methods encourage us not to feel embarrassed about ourselves. There is nothing to be embarrassed about. It’s like ethnic cooking. We could be proud to display our Jewish matzo balls, our Indian curry, our African-American chitlins, our middle-American hamburger and fries. There’s a lot of juicy stuff we could be proud of. Chaos is part of our home ground. Instead of looking for something higher or purer, work with it just as it is.

The world we find ourselves in, the person we think we are—these are our working bases. This charnel ground called life is the manifestation of wisdom. This wisdom is the basis of freedom and also the basis of confusion. In every moment of time, we make a choice. Which way do we go? How do we relate to the raw material of our existence?

These are three very practical ways to work with chaos: no struggle, poison as medicine, and regarding everything that arises as the manifestation of wisdom. First, we can train in letting the story lines go. Slow down enough to just be present, let go of the multitude of judgments and schemes, and stop struggling.

Second, we can use every day of our lives to take a different attitude toward suffering. Instead of pushing it away, we can breathe it in with the wish that everyone could stop hurting, with the wish that people everywhere could experience contentment in their hearts. We could transform pain into joy.

Third, we can acknowledge that suffering exists, that darkness exists. The chaos in here and the chaos out there is basic energy, the play of wisdom. Whether we regard our situation as heaven or as hell depends on our perception.

Finally, couldn’t we just relax and lighten up? When we wake up in the morning, we can dedicate our day to learning how to do this. We can cultivate a sense of humor and practice giving ourselves a break. Every time we sit down to meditate, we can think of it as training to lighten up, to have a sense of humor, to relax. As one student said, “Lower your standards and relax as it is.”

- No more struggle: “Whatever arises, train again and again in seeing it for what it is. The innermost essence of mind is without bias. Things arise and things dissolve forever and ever. Whatever happens, we can look at it with a nonjudgmental attitude. This is the primary method for working with painful situations.”

- Using poison as medicine: “When suffering arises, we breathe it in for everybody. This poison is not just our personal misfortune. It’s our kinship with all living things, the seed of compassion and openness. Instead of pushing it away or running from it, we breathe in and connect with it fully. We do this with the wish that all of us could be free of suffering.”

- Regarding whatever arises as awakened energy: “This reverses our habitual pattern of trying to avoid conflict, trying to smooth things out, trying to prove that pain is a mistake that would not exist in our lives if only we did the right things. This view encourages us to look at the charnel ground of our lives as the working basis for attaining enlightenment.”