By Steve Taylor PhD: The Transformational Effect of Letting Go of Resentment…

Recently I met a woman called Sena, whose brother was killed 13 years ago. Tony, her brother, was working as a chef in the British army, when he was shot by one of the soldiers in his own unit. The soldier claimed it was an accident, that the gun had just gone off as he put it over his knees. He was eventually sentenced to two years in prison for manslaughter. The death was made even more tragic by the fact that Tony’s wife was pregnant with their first child.

Sena’s life was thrown into disarray. She had a psychological breakdown, couldn’t work or sleep, and was put on strong psychiatric drugs. She became timid, felt that she couldn’t face the outside world, and didn’t leave her house for months. It was made worse by the media attention which the incident caused. The investigation and trial lasted for more than two years, and as Sena told me. “We lived in a small town where nothing ever happened, so it was big news, and always featured in the local newspaper and on local television.”

Sena’s difficulties continued until six years ago, when she began to go through a process of healing, the main feature of which was forgiving the man who killed her brother. As she describes it:

“I realised that it wasn’t serving any purpose for me to be so full of hatred and bitterness. All it was doing was causing intense pain inside me. It definitely wasn’t serving my purpose. So I decided to let go. I realised that he [the man who killed her brother] was no different to me. He said it was an accident, and I was sure he felt remorse about it. I knew that it was the right thing to do, to forgive him. And it had an immediate effect. I felt lighter and freer, as if I’d suddenly let go of about 40 years of ageing. It felt like my life could begin again.”

Since then Sena’s life has turned around. She feels that the experience has deepened and expanded her, and enabled to live a richer and more meaningful life.

Letting Go

It’s certainly not easy to forgive. If someone has wronged you – inflicted pain, humiliated you, abused or exploited you – it’s entirely natural to feel bitterness and resentment. That’s surely what they deserve. Surely what they don’t deserve is our empathy and understanding, and certainly not our charity. Surely to forgive them just “lets them off the hook” and gives them licence to mistreat others.

But there are good reasons why forgiveness is worthwhile. A prolonged, constant sense of resentment doesn’t punish the person who wronged you, but only yourself. Carrying resentment – or a grudge against someone – drains of us our energy and well-being. It creates tension inside us, makes us rigid, and creates a general sense of negativity which seeps through the whole of our lives. In a sense therefore, by carrying resentment, we allow the person to continue hurting us. An act of forgiveness, therefore, means releasing this resentment, freeing ourselves from the tension and rigidity which comes with carrying a grudge.

Research has shown how beneficial forgiveness can be. In a study at Stanford University, 259 people were assigned to either a nine hour “forgiveness workshop” or to a control group. At the end of the workshop, the workshop participants reported significantly lower levels of stress and anger, and more optimism and better health. (1)

You might assume that, if you had the opportunity to take revenge on someone who has wronged you, this would give you a tremendous sense of well-being, a sense of catharsis which would purge you of your resentment and make you feel liberated. But research has shown that this is generally not the case. Whereas people who don’t seek revenge tend to “move on,” people who take revenge continue to ruminate about the situation, which prolongs the negativity. Situations which may have been seen as trivial are inflated and inflamed. The “catharsis” of revenge only leads to more bitterness and resentment. (2)

And in any case, acts of revenge are counterproductive in the long run. They only set up a cycle of violence which leads to more hatred, hurt and destruction on both sides.

Empathy and Understanding

I’m aware that this is very idealistic, of course. The idea of offering complete forgiveness to someone who has wronged you may be a step which you’re unwilling to take. It may depend on the severity of the incident, and how strongly it has affected you.

However, there are some intermediate points between vengefulness and complete forgiveness. It may help simply to try to understand the person’s perspective, and look at the reasons for their actions. Did they really intend to hurt you? And even if they did, were they really responsible for their actions? If they really are “evil” in some way, perhaps this is due to factors beyond their own control – for example, psychological or personality problems, or environmental factors. Perhaps they suffer from low self-esteem, insecurity, or a psychiatric disorder. Perhaps they had a terrible upbringing which has scarred or traumatized them. It’s also worth remembering that people who hurt and humiliate others are usually full of psychological disord themselves, and most likely extremely unhappy.

It doesn’t really matter conclusions you come to – the simple act of empathising with the person may release some of your resentment.

And once you’ve reached that point you may feel that you can further, to the point of forgiveness. In Sena’s experience, forgiveness was sudden and immediate, but according to the psychologists Enright, Freedman and Rique, the process normally has four stages. First, there is the “Uncovering Phase,” where you become aware of the negative effect your resentment is having on your life. Second, there is the “Decision Phase,” when you decide to let go of your resentment. Next is the “Work Phase,” where you cultivate your forgiveness, by accepting what has happened and trying to empathize with the offender. Finally, there is the “deepening phase,” in which your forgiveness leads to a deeper understanding of yourself and of life in general; you might, for example,develop a sense of empathy and compassion for others who have suffered in a similar way. (3)

We shouldn’t, therefore, think that forgiveness means letting the wrongdoer “off the hook.” We should forgive for ourselves, not for them. If anything, forgiveness means letting ourselves “off the hook” – that is, freeing ourselves from unnecessary anger and bitterness, which – as Sena put it – serves no purpose and blights ourselves our lives with negativity. As the saying goes, “The best revenge is living well.”

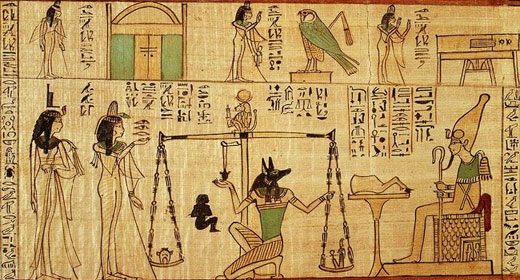

Perhaps we also have a collective responsibility to forgive, as a way of avoiding (or at least mitigating) the conflicts and wars which still rage throughout the world – all of which began and are continually inflamed by resentment, and which will keep raging until empathy and understanding overcome resentment. As Archbishop Desmond Tutu has written, “Forgiveness is an absolute necessity for continued human existence.”