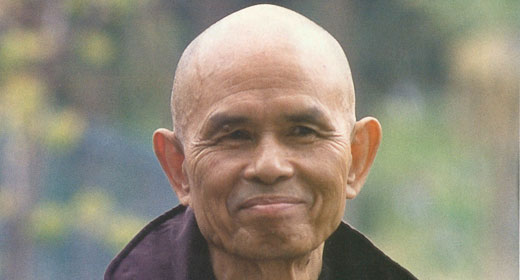

by: Nadia Colburn: I know of no spiritual teacher or person who more fully embodies peace and compassionate understanding than Thich Nhat Hanh,

or Thay, as he is lovingly known by his students. “All religions and spiritual traditions,” William James famously wrote, “begin with the cry ‘Help!’” Like so many, I began my spiritual quest in earnest when I began to heal consciously from an instance of violence in my early childhood and the pain and confusion around it. Why, I wanted—I needed—to know, did bad things happen, not only on the personal level, but all around us in the world? The world is full of injustice and destruction: how are we to understand our present moment and transform it? I needed a larger frame.

I had read the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh’s work before, and I knew to go back to his writing and teachings. When Thay teaches that the present moment is a wonderful moment, he is not speaking from a position of naïve privilege.

Thay lived through the Vietnam War and saw immense pain, violence, suffering, and tragedy firsthand. He broke with the established Buddhist leaders and urged greater engagement; together with other young activists, Thay went into the countryside, where the fighting was worst, and provided support—rebuilding towns, schools, villages. He risked his own life many times, and many of his close friends and colleagues were killed.

Exiled from Vietnam in 1968 because of his peace work, Thay settled in France and continued to work steadfastly for peace and to help those displaced and suffering from the war and its aftermath. I find his early journals especially moving: we see him, confronted with the violence of the war, time and again overcome his own despair. We see him, in his early exile, far from the country and people he loves, feeling homesick, unable to sleep, and learning to make a new home in his new surroundings, keeping his spirits up.

At the heart of his teachings is the insight that peace starts from within. In the face of the self-righteous conviction of each side in the civil war, in the face of people so sure they are right they are willing to kill or be killed for their ideals, Thay realizes that the only true path to peace is to find and grow peace within each of us, to cultivate compassion and understanding, and to understand how we all are interconnected.

Many of Thay’s most moving teachings come in the form of poems. In his poem “Call Me by My True Name,” written in 1978, he remembers with sorrow the many Vietnamese who died trying to escape their country on boats—in a situation not dissimilar from that of many Syrian refugees today. In this poem, Thay explores entering into the experiences of many different beings: I am, he writes, “a bud on a spring branch,” a “frog swimming happily,” a “child in Uganda all skin and bones.” In perhaps the most powerful stanza he assumes the roles of both victim and perpetrator:

I am the twelve year old girl

refugee on a small boat,

who throws herself into the ocean

after being raped by a sea pirate.

And I am the pirate,

my heart not yet capable

of seeing and loving.

Thay tries to see every side, every being, with understanding and compassion. He continues:

Please call me by my true names,

so I can hear all my cries and laughter at once,

so I can see that my joy and pain are one.

At the heart of Buddhist teaching is the idea of non-self. And Thay emphasizes this: we inter-are. We are the cloud whose rain falls into the earth and helps grow the food that we eat. We are our joys and our pains, our mothers and fathers, our teachers and everything that we ever come into contact with.

I had originally been asking the question “Why?” But Thay taught me to come out of my head and into my heart. How do I show compassion, first to myself for my own suffering, and then to all others? Through his own example of coming to a place of peace and joy from suffering, I trusted his directions.

How do you cultivate peace and happiness? His answer is to meditate: practice; breathe; pay attention to your breath; pay attention to the present moment; pay attention to the miracle of being alive; wake up; and again come back to your breath. This practice calms the mind and body and develops concentration. And from this concentration, one has the insight to see into suffering and cultivate wise compassion and understanding and appreciation.

In Thay’s engaged Buddhism, meditation is not only what we do in silence on our cushion, but what we attempt to do all day long, with every step and every breath: we come back into awareness, and from this awareness we come to be the peace:

Breathing in, I calm my body,

Breathing out, I smile,

Dwelling in the present moment,

I know this is a wonderful moment.

In a time of such violence on a global scale, such insecurity and such devastation to the landscape, I think it’s important that we all learn to practice peace. We practice not only to eliminate suffering, but to transform on the personal and the social levels, and to wake up so that we are capable of really celebrating the great miracle of life.