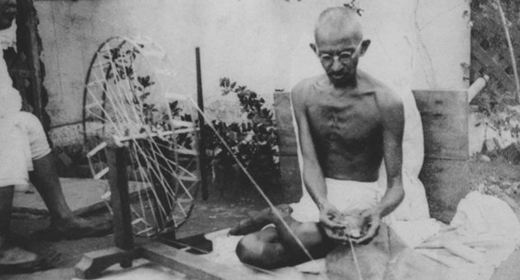

Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of the movement for India’s independence from Great Britain and the man considered the father of the country by many Indians,

was hardly a wallflower of the civil rights movement. “My life is my message,” he famously reflected later in life. And indeed, he used his own actions and image as an example for others to follow—from his adherence to the truth (Satyagraha) to his public spinning of the traditional fabric he dressed in while boycotting British textiles to using his own dwindling flesh as a tool of nonviolent protest.

He was a man constantly surrounded by people. He led hundreds of thousands of his supporters on marches across the country, delivered countless speeches, lived on a communal Ashram among his students and followers, and even gleaned valuable insights from interacting with his fellow inmates during his eleven periods of incarceration.

Dumbstruck—but dedicated to truth

Gandhi didn’t always relish the company of others. In his Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth, Gandhi wrote of his childhood:

“…I used to be very shy and avoided all company. My books and my lessons were my sole companions. To be at school at the stroke of the hour and to run back home as soon as the school closed—that was my daily habit. I literally ran back, because I could not bear to talk to anybody. I was even afraid lest anyone should poke fun at me.”

Like many introverts, he initially saw his constitutional shyness as a liability and tried to “overcome” it. Between the eras of his grade-school awkwardness and his political and spiritual awakening, Gandhi left his home in Porbander, India, to study law in London. While there, he tried to fit in socially by taking locution, French and dance classes, and investing in the latest fashions, including spats, a top hat, and a silver-handled cane. Having been brought up vegetarian, lapsed, and then rededicated to meat-abnegation, the newly foppish Gandhi also became active in local vegetarian clubs and in so doing developed a taste for community organizing. Nonetheless, his shyness persisted:

“This shyness I retained throughout my stay in England. Even when I paid a social call the presence of half a dozen or more people would strike me dumb.”

As a young man, Gandhi had not been particularly religious or even spiritual. Nonetheless, he always had great dedication to the notion of truth as both a moral compass and a heuristic for solving practical problems. In his early career, this dedication to truth sometimes took the shape of speaking truth to power, with mixed results. After a confrontation with an English officer in India, he became disgusted and chased a job opportunity in South Africa rather than compromise his ethics and kowtow to the offending officer to salvage his career at home.

Once in South Africa, he became invested in the plight of the disenfranchised Indian workers there, and when he returned to India, his burgeoning political activism and philosophical investigations led to what is generally known as Gandhism—although Gandhi himself objected to the term, saying,

“I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and nonviolence are as old as the hills.”

The truth that Gandhi found, mostly by looking within himself, drove him to become the paradigm of the self-denying crusader for social justice. One of his most difficult denials was surely suppressing his innate aversion to public interaction.

“My shyness has been…my shield”

Unlike many public figures who “overcome” their introversion, however, Gandhi eventually recognized the benefit of his own reticence:

“I must say that, beyond occasionally exposing me to laughter, my constitutional shyness has been no disadvantage whatever. In fact I can see that, on the contrary, it has been all to my advantage. My hesitancy in speech, which was once an annoyance, is now a pleasure. Its greatest benefit has been that it has taught me the economy of words. I have naturally formed the habit of restraining my thoughts. And I can now give myself the certificate that a thoughtless word hardly ever escapes my tongue or pen. I do not recollect ever having had to regret anything in my speech or writing. I have thus been spared many a mishap and waste of time.

Experience has taught me that silence is part of the spiritual discipline of a votary of truth. Proneness to exaggerate, to suppress or modify the truth, wittingly or unwittingly, is a natural weakness of man and silence is necessary in order to surmount it. A man of few words will rarely be thoughtless in his speech; he will measure every word. We find so many people impatient to talk. There is no chairman of a meeting who is not pestered with notes for permission to speak. And whenever the permission is given the speaker generally exceeds the time-limit, asks for more time, and keeps on talking without permission. All this talking can hardly be said to be of any benefit to the world. It is so much waste of time. My shyness has been in reality my shield and buckler. It has allowed me to grow. It has helped me in my discernment of truth.”

The above quote functions not only as a positive spin on Gandhi’s social anxiety but also as a defense of introversion in general.

How much more meaningful work could we get done if thoughtfulness and deliberation were rewarded as much as exposition and bluster? And how many interminable life-force-draining meetings and conference calls could be truncated or altogether obviated if the concision bred of preparatory contemplation was recognized as one of the hallmarks of leadership? Just the thought of such a utopia evokes sighs of relief.