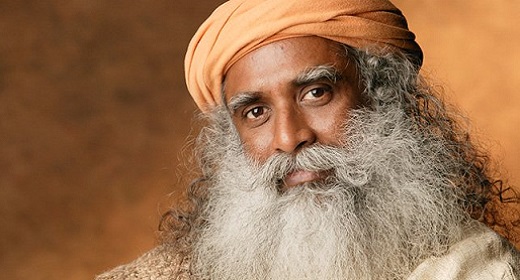

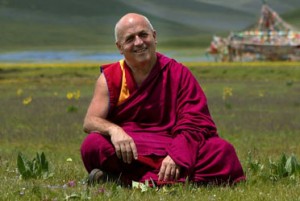

August, 2009 Matthieu Ricard has been a key contributor to the increasingly fruitful dialogue between scientists and spiritual practitioners, and a regular subject for scientific experiments on meditation.  Here he explains some of the findings, and the implications for the future.

Here he explains some of the findings, and the implications for the future.

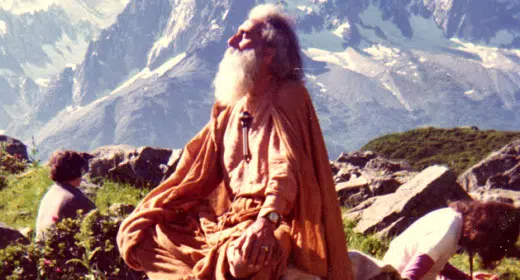

by Matthieu Ricard: In 2000, a remarkable meeting took place in Dharamsala, India. Some of the leading specialists on human emotions—psychologists, neuroscientists and philosophers—spent an entire week in discussion with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in the privacy of his home in the foothills of the Himalayas.

It was the first time that I had been able to participate in the fascinating meetings held by the Mind and Life Institute, which was founded in 1987 by Francisco Varela, a renowned neuroscientist, and Adam Engle, an American businessman. The dialogues focused on destructive emotions and how to handle them.1

One morning, during the meeting, the Dalai Lama declared: “All of these discussions are very interesting, but what can we really contribute to society?” During the lunch break, the participants engaged in animated discussions that resulted in a proposal to launch a research programme on the short- and long-term effects of mind training, generally known as ‘meditation’.

That afternoon, in the presence of the Dalai Lama, the project was enthusiastically adopted. It marked the start of an exciting research programme—that of ‘contemplative neuroscience’.

These studies seem to demonstrate that the brain can be trained and physically modified in a way that few people would have imagined

Several studies were launched: in the laboratories of the late Francisco Varela in France; of Richard Davidson and Antoine Lutz in Madison, Wisconsin; of Paul Ekman and Robert Levenson in San Francisco and Berkeley; of Jonathan Cohen and Brent Field in Princeton, Stephen Kosslyn in Harvard, and Tania Singer in Zurich. I had the good fortune to participate in these studies from the outset.

Following an initial exploratory phase, about twenty experienced meditators were tested: monks and laypeople, men and women, easterners and westerners. All of them had devoted between 10,000 and 50,000 hours to meditation—to developing compassion, altruism, mindfulness and awareness.

These studies led to the publication of several articles in prestigious scientific journals,2 establishing the credibility of research on meditation and on achieving emotional balance, an area which had not been taken seriously until then.

In the words of Richard Davidson: “These studies seem to demonstrate that the brain can be trained and physically modified in a way that few people would have imagined.”

Stephen Kosslyn, Director of the Psychology Department at Harvard University and a world specialist in mental imagery, declared during the Mind and Life meeting held at Boston’s Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): “We should feel humble in the face of the amount of empirical data that the Buddhist contemplatives have accumulated over the centuries.”

A global benefit

Experienced meditators have the ability to generate mental states that are precise, focused, powerful and lasting. In particular, experiments have demonstrated that the region of the brain associated with emotions such as compassion, for example, showed considerably higher activity in those with long-term meditative experience. These discoveries indicate that basic human qualities can be deliberately cultivated through mental training.

Other scientific experiments have also shown that one does not have to be a highly trained meditator to benefit from the effects of meditation, and that twenty minutes of daily practice can contribute significantly to the reduction of anxiety and stress, the tendency to become angry (the harmful effects of anger on health are well established), and the risk of relapse in cases of severe depression.

Thirty minutes a day of mindfulness meditation (of the MBSR type)3 over the course of eight weeks results in a considerable strengthening of the immune system and of one’s capacity for concentration, as well as a reduction in arterial tension in subjects suffering from hypertension, and faster healing of psoriasis.4

When it comes to practice, what is essential is not to meditate for long periods of time, but to meditate regularly. If the brain is engaged regularly, modifications in the neuronal system can be observed after about thirty days. The study of the influence of mental states on health, once considered fanciful, is now increasingly part of the scientific research agenda.5

Without dramatizing, it is important to underline the degree to which meditation and ‘mind training’ can change our lives. We tend to underestimate the power of transforming our own minds and the effect that this ‘inner revolution’, which is profound and peaceful, can have on our quality of life.

Change can come at any age

The Dalai Lama often describes Buddhism as being, above all, a science of the mind. That is not surprising, because the Buddhist texts put particular emphasis on the fact that all spiritual practices—mental, physical and oral—are directly or indirectly intended to transform the mind.

Nevertheless, as Mingyur Rinpoche writes: “Unfortunately, one of the main obstacles we face when we try to examine the mind is a deep-seated and often unconscious conviction that ‘we’re born the way we are and nothing we can do can change that’.”6

A renowned psychoanalyst was asked the following question about Ingrid Betancourt, a French-Colombian politician who was kidnapped while campaigning in Colombia: “Can six years of detention in extreme conditions alter one’s personality?” His response was: “No. After the age of twenty-five, your personality is fixed.”

Personally, it was around the age of twenty-five that I really began to change! This was also the case for most of the meditators who took part in the research; they changed from the moment they began to seriously engage in a process of training the mind through meditation.

To what extent can we train our mind to work in a constructive manner, to replace obsession with contentment, agitation with calmness, hatred with kindness?

One of the great tragedies of our time is that we significantly underestimate our capacity for change

Twenty years ago, it was almost universally accepted by neuroscientists that the brain contained all its neurons at birth, and that their number did not change with experience.

We now know that new neurons are produced up until the moment of death, and we speak of ‘neuroplasticity’, a term which takes into account the fact that the brain evolves continuously in relation to our experience, and that a particular training, such as learning a musical instrument or a sport, can bring about a profound change. Mindfulness, altruism and other basic human qualities can be cultivated in the same way, and we can acquire the ‘know-how’ to enable us to do this.

One of the great tragedies of our time is that we significantly underestimate our capacity for change. Our character traits continue as long as we do nothing to improve them, and as long as we tolerate and reinforce our habits and patterns, thought after thought, day after day, year after year.

Studies asserting that 40 to 60 per cent of our character traits are determined by genetics are contested by neuroscientists working in the fields of neuroplasticity and by specialists in epigenetics, the study of gene expression, an area of research which is growing rapidly.

Genes are a bit like a blueprint that may or may not be put into action—there is nothing absolute about it. Even in adulthood, our environment can have a considerable influence on the expression of genes.

Unlocking our true potential

We do not consider it strange to devote years to learning to walk, read and write, or to training for a profession. We spend hours exercising to stay in good physical shape, pedalling away on exercise bikes that go nowhere. In order to embark on any task, we need to have at least a small level of interest or enthusiasm, and that comes from being aware of the benefits.

So why on earth should the mind be exempt from the same logic? Why should it be able to transform itself without the slightest effort, simply because we want it to? Such an assumption makes about as much sense as hoping to be able to play a Mozart concerto simply by tapping on the piano keys from time to time.

We are all a mixture of light and shadow, strengths and weaknesses. Our mind can be our best friend, and our worst enemy. But this state of affairs is neither optimal nor inevitable. We all have the potential to free ourselves from mental states that cause suffering for ourselves and others, to find inner peace and to contribute to the well-being of others. But just wishing for this is not enough. We need to train our minds.7

These methods, when secularized and scientifically validated, could be integrated into children’s education programmes, for example, as a kind of mental equivalent of physical education

We devote a lot of effort to improving the material conditions of our existence, but in the end it is always our mind that experiences the world and translates this experience into well-being or suffering. By transforming the way we perceive things, we transform the quality of our lives; and such a change can come from training the mind through meditation.

In Buddhism, ‘to meditate’ means ‘to get used to’ or ‘to cultivate’. Meditation consists of getting used to a new way of being, of perceiving the world and mastering our thoughts.

We often hear that Buddhism aims to eliminate the emotions. That all depends on what we mean by ’emotion’. If we mean those that disturb our mind, such as hatred, anxiety and jealousy, why not get rid of them? If, on the other hand, we mean feelings of altruistic love and compassion towards those who are suffering, why not develop them? In any case, this is the purpose of meditation.

To accomplish this purpose, Buddhist meditation uses two methods: one analytical, the other contemplative. Analysis consists of examining the nature of reality, which is essentially interdependent and impermanent, and honestly evaluating the causes and results of our own sufferings, and those that we inflict on others.

The contemplative approach consists of turning our mind inward and observing, behind the veil of thoughts and concepts, the nature of ‘pure awareness’ which underlies all thoughts and allows them to arise. This fundamental ‘knowing’ exists even in the absence of thoughts and concepts.

Practical implications of this research

These methods of meditation, when secularized and scientifically validated, could be integrated into children’s education programmes, for example, as a kind of mental equivalent of physical education. They could also be brought into therapy for adults with emotional problems.

For the past three years, the neuroscientists, sociologists, educators, psychologists and contemplatives who regularly take part in Mind and Life meetings have held several smaller workshops in addition to their discussions with the Dalai Lama. They have discussed in particular how programmes could be introduced in education, in a completely secular way, to develop altruism, emotional balance and mindfulness, and to reduce stress.

A fully-fledged Mind and Life meeting on this subject will take place in Washington DC in October 2009. A programme will then be introduced in several schools in the United States, and the results will be compared with those from a control group.

These recent scientific discoveries have changed our understanding of the way in which the brain evolves during the course of a lifetime. There is a growing recognition that this is not mere fantasy, and that it takes us to the heart of neuroscience and neuroplasticity, areas which are themselves relatively new.

At the same time, the increasingly powerful Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) techniques and increasingly sophisticated electroencephalograms (EEG), combined with the participation of experienced contemplatives, have led us towards a golden age of ‘contemplative neuroscience’. It is a fascinating prospect, and there is so much more to discover.