by Patricia Sullivan: The man who introduced transcendental meditation to the West, who briefly became a guru to the Beatles and other pop musicians

and who built a multimillion-dollar global business based on teaching people how to pause and close their eyes twice a day, died Feb. 5 at his home in Vlodrop, Netherlands. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was thought to be 91.

The Maharishi, a Hindi title that means “great seer,” had announced last month that he would withdraw from day-to-day administrative duties to complete his commentaries on the Veda, the ancient Indian texts that underpin his movement. No cause of death was reported.

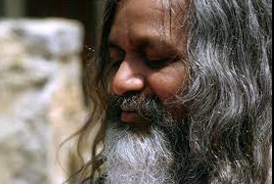

The spare, self-effacing leader, once known as the “Giggling Guru,” appeared on newsmagazine covers and on Merv Griffin’s talk show in the 1960s and 1970s. In recent years, he had confined himself to two rooms in his Dutch log house, accessible only to a small group of aides, and he communicated primarily by videoconference. A bald head replaced his long hair, although his profuse beard remained.

He still exercised global influence, derived from the 6 million people his organization said have been trained in transcendental meditation, a technique of quiet “restful alertness” based on quietly repeating a Sanskrit word. Advocates say the practice can lead to clearer thinking, improved health, increased creativity and ultimately, enlightenment. If enough people practiced it, the Maharishi said, world peace would follow. His course cost $2,500.

The Maharishi began promoting the technique in the United States in 1959, but it wasn’t until the Beatles met him in 1967 that he became widely known. The four members of the world’s best-known band renounced illicit drugs and, along with singer Mike Love of the Beach Boys, folk singer Donovan, actress Mia Farrow and her sister Prudence, moved to his ashram in India the following year to study.

The venture ended badly. None of the Beatles completed the three-month course, and they circulated unproven allegations of sexual improprieties by the Maharishi, who said he was celibate. Others said the Beatles resumed drug use at the ashram. John Lennon wrote many songs while he was there, but it was his bitter “Sexy Sadie” that described his ultimate opinion: “Sexy Sadie what have you done/You made a fool of everyone.”

“We made a mistake,” Paul McCartney later said. “We thought there was more to him than there was. He’s human. We thought at first that he wasn’t.”

The exposure brought the Maharishi fame that waned after the 1970s but never really vanished.

Five years ago, declaring that he was tired of waiting for governments to bring about peace, he asked his many well-wishers to take on the task. They were to gather near the trouble spots around the world and meditate.

“Problems will disappear as darkness disappears with the onset of light,” he promised.

Part of the problem with the long-promised, long-delayed advent of world peace was that the government capitals were in the wrong places, he said. For example, the White House should face east for optimal harmony, and in fact the entire federal government should move to Smith Center, Kan., near the geographic center of the 48 contiguous states and the nation’s center of energy, he said.

That idea rather alarmed the town of 1,800, as did the movement’s purchase of 1,100 acres of prime farmland in 2006 with plans to build a “World Center of Peace” and import hundreds of residents.

The Maharishi had overcome similar provincial fears in 1974, when he founded a university in Fairfield, Iowa. His followers later founded Maharishi Vedic City nearby. There are thousands of his transcendental meditation teaching centers around the world. His organization’s $3.5 billion in assets include a chain of hotels, a health food distribution network and a veritable library of instructional books and videotapes, in addition to real estate holdings that include a five-story, 20,000-square-foot building near the New York Stock Exchange.

The Maharishi recently vowed to raise $10 trillion to end poverty by sponsoring organic farming in the world’s poorest countries.

He was born Mahesh Prasad Varma in Uttar Pradesh, India. Much of his early life, including his birthdate, is in dispute, and the Maharishi declined to discuss his youth. Some sources say he was born in 1911, which would have made him 96 or 97, but a spokesman for the transcendental meditation movement said he was 91.

The Maharishi studied physics at Allahabad University, then became a secretary and follower of a prominent Hindu sage Swami Brahmananda Saraswati Shankaracharya of Jyotir Math, also known as Guru Dev.

After his teacher died in 1953, the young man retreated into the Himalayas for two years of meditation. When he emerged, he devoted himself to popularizing his master’s form of meditation, which was derived from the Hindu belief of Vedanta. The belief holds that God is to be found in every creature and object, that the purpose of human life is to realize the godliness in oneself and that religious truths are universal.

In 1963, he finished his first major book, “The Science of Being and Art of Living,” and in 1965 he completed his commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita, a sacred Sanskrit text.

He encouraged scientific investigation of his claims, and a number of studies found beneficial physical and mental effects for people who regularly practiced transcendental meditation.

The Maharishi moved to the Netherlands in 1990, drawn to the tolerant nature of its people. Few saw him, as he emerged only a few times each year for fresh air on a chauffeured drive, the New York Times reported in 2006.

His introduction of “yogic flying” as an advanced meditation technique, which he had described as levitation, brought scorn from critics who said it was nothing more than cross-legged hopping. They called him a fraud. But when it is performed by a critical mass of people, the Maharishi said, it would lead to peace.