by Estes Park of the Denver Post: When B.K.S. Iyengar strides into the vast room at the YMCA of the Rockies, clad in white dhoti and kurta, people fall to their knees and kiss his feet.  Beaming, he tries to move forward, but each step is blocked by prostrating waves of human gratitude.

Beaming, he tries to move forward, but each step is blocked by prostrating waves of human gratitude.

The aging yogi gets the rock-star treatment throughout his visit to the 10th Annual Yoga Journal Colorado Conference. During a surprise appearance at one of the classes, everything stops as people flock toward him, including a tall brunet who blasts past his tight security to quickly grab his arm.

“Sir, thank you so much!” she says, kissing his hand.

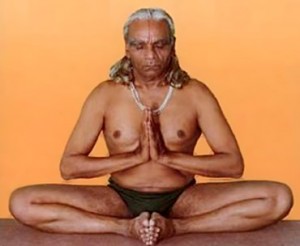

At 87, this 5-foot barrel-chested cultural icon is considered the world’s greatest living yoga teacher, the person most responsible for the tremendous popularity of yoga in America, thanks to seeds he planted in the 1970s. Today, 16.5 million people practice yoga, spending nearly $3 billion each year on classes and products.

Last year, Time magazine named Iyengar one of the 100 most influential people in the world, shortly after the word “Iyengar” made it into the Oxford English Dictionary.

His classic book “Light on Yoga” has sold more than 1 million copies, and has been translated into 17 languages.

Now people are grabbing up his latest book, “Light on Life,” which hit bookstores Oct. 1. Before starting the five-city book tour, expected to attract tens of thousands of people from New York to Los Angeles, Iyengar flew to Colorado to teach a three-day yoga intensive for yoga teachers and students.

All 800 tickets sold out in 10 minutes, attracting people from all over the United States, and as far away as South Africa.

On this last day, people are packed mat to mat, including Oscar-nominated actress Annette Bening, a longtime Iyengar student, and such yogic luminaries as Rodney Yee and Baron Baptiste.

Iyengar no longer practices yoga in public, although he continues a disciplined daily practice, hours of yoga with heavy focus on backbends, which helped him avoid the hunchback that plagues many octogenarians.

Onstage are Iyengar’s senior teachers, chosen to demonstrate his instructions. Students know he is a taskmaster, someone who kicks and slaps students who fall short of his merciless quest for perfection. That very morning, he had even brought up his harshness the previous day: “Some are irritated with me,” he says. “Some say I am a cruel man. But I lose my temper when I see people doing wrong.”

In his version of tough love, a slap brings intelligence to that part of the body, freeing the student from habitual patterns.

Midway through this rainy morning, as 800 people pant through a particularly long headstand, Iyengar shouts at them to stop immediately. Turning to the woman demonstrating the pose onstage, he barks that she must show it properly, once again.

But as she starts to move into headstand he slaps her, hard, a resounding whack on the back. Her head jerks up. She struggles to hold back tears, takes a deep breath, and then rises up into a headstand that looks flawless.

The class moves on, straining to catch each nuance of this intense, demanding lesson.

At this point, astonished and disgusted, a 32-year-old yoga student from Broomfield quietly rolls up his mat.

“I came expecting to study with this living guru, but I had to walk out,” says Hayden Hernandez. “He was incredibly disrespectful and rude the whole time, physically and verbally abusive to everyone. He hit that woman hard enough for her to cry out.”

But Iyengar’s flashes of anger pose no problem to the faithful, who reverently call him “Guruji.” Some even joke that B.K.S. – short for his name, Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja – really stands for “beat, kick, slap.”

Americans tend to deify their favorite yogis and swamis. In reality, most are imperfect people facing the same struggles that hamper everyone else.

Gen-X’er Todd Semo, a former martial artist who teaches Iyengar yoga in San Francisco, just returned from studying for two months with Iyengar in India, where he received a whack of his own.

“If you believe what he’s doing is in your best interest and not merely to serve his ego, then you understand the slap on elbow or thigh,” he says.

“It reverberates in your body for years when you do that pose again. He has the ability to touch your skin, your muscle, and your bone at an energetic level. He’s graced with something, and to be touched by him is a blessing.”

When Iyengar first started teaching yoga, in the 1930s, people laughed at him. No one dreamed he would ever amount to anything, much less a world-famous yogi.

“I was an anti-advertisement for yoga,” says Iyengar, then a scrawny weakling with a chest that measured a mere 28 inches.

His childhood was a litany of diseases, including tuberculosis, malaria and typhoid. Twice he had considered suicide to escape the misery. At age 14, his brother-in-law finally showed him some yoga poses to help heal his body, but it was not an auspicious start.

“When I bent forward, my middle finger could not touch my knees,” he says.

His brother-in-law happened to be the legendary Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, credited with creating the physical, or hatha, yoga now practiced by millions of people from Europe to Asia.

“Whether it came from the Yogarahasya, a lost ancient text that appeared to him in a dream, or a palm-leaf manuscript called the Yoga Korunta (supposedly devoured by ants), or from a blend of asana, pranayama, Indian wrestling, and British gymnastics, Krishnamacharya’s yoga represents a uniquely 20th-century incarnation of a rich and ever-evolving tradition, the underlying tenets of which have wavered little since the time of the Upanishads,” according to Yoga Journal.

His disciples included Pattabhi Jois, who eventually started the popular school of Ashtanga Vinyasa yoga now practiced by celebrities including Madonna. He also taught yoga master T.K.V. Desikachar, who later developed the Viniyoga style taught at studios like the Whole Yoga School in Denver.

Krishamacharya frequently lost his temper with Iyengar, his blows falling on the boy like an iron rod. If Iyengar could not put his feet on his head, his guru denied him food until he could. Sometimes it took two or three days before he earned the meal.

Once, Krishnamacharya forced him to do a pose – one leg back, one leg forward, sitting down with straight legs – that he had never before performed. This resulted in a torn ligament and the inability to walk for two years.

“My guru had stern discipline,” says Iyengar. “Gradually a fear complex grew in me.”

Yoga pupils frequently ran away from Krishnamacharya, often in the dead of night. When his star student vanished just days before an important yoga demonstration, Krishnamacharya looked to Iyengar, who felt trapped. He lived with his eldest sister and Krishnamacharya in the beautifully landscaped palace of the Maharajah of Mysore, who had hired the legendary guru to teach yoga to the royal family.

With no one left to control, Krishnamacharya was forced to use Iyengar for that demonstration. It worked well, however, so he took Iyengar on the road to perform thousands of yoga demonstrations across India. Then he sent him off to teach yoga to women in northern India, where Iyengar began to explore the therapeutic affects of yoga, down to the cellular level.

In 1937, working with a surgeon who believed in the power of yoga to heal, he absorbed lessons in anatomy and medicine, developing a style of yoga known for precision, alignment and use of props to make poses accessible to those with physical ailments.

The first patient that surgeon sent Iyengar suffered from such a bad case of dysentery that he could neither walk nor stand. Still, the young yogi cured him with a few simple poses.

Over the years, word of Iyengar’s miraculous ability to heal spread around the world. In 1956, the same year Iyengar taught 80-year-old Queen Elisabeth of Belgium to stand on her head, Standard Oil heiress Rebekah Harkness invited him to visit the United States.

“I saw Americans were interested in the three W’s – wealth, women and wine,” he says.

“I was taken aback to see how the way of life here conflicted with my own country. I thought twice about coming back.”

For 17 years, he refused to return. By the time he finally relented – “a student came to my hometown and tempted me to visit” – the Beatles had popularized Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and America was ripe for spiritual transformation.

On Friday afternoon, before a packed auditorium, Annette Bening is onstage facing the formidable Iyengar, ready to conduct a question-and-answer session with her teacher.

Wearing a plum-colored tunic over black yoga pants, she sits ramrod straight, bare feet perfectly parallel on the oriental carpet.

She looks nervous. If Iyengar publicly chastises his beloved senior instructors, puncturing any shred of ego, no telling how he’ll treat her.

But in the end, he merely upstages the movie star, shortly after she asks him about lust.

Bening reads from Iyengar’s new book, revealing that women constantly threw themselves at him, so that he developed a forbidding manner – those flashing eyebrows, that piercing glare – to keep them at arm’s length.

“One woman even said, ‘I would like to kiss your legs that stretched so well,”‘ he adds, triggering a paroxysm of audience laughter.

Suddenly, the irascible, irrepressible Iyengar leaps to his feet. He summons a few senior teachers to the stage, and catapults them into a long demonstration. By the time he’s finished, there’s no time left.

Bening madly skims her long list of things unanswered, trying to cram in one last question.

“Here’s one on bliss, the divine body,” she says. “Or – no! It’s so hard to choose. Tell us about the four stages of life.”

In old age, Iyengar has become quite cosmic. In the competitive world of yoga, many have mistakenly derided him as mastering only hatha, or physical, yoga. Purists claim that real yoga is Raja or Ashtanga yoga, an eight-limbed system of ethics and meditation created millennia ago by the ancient sage Patanjali. Hatha yoga is just one of the eight limbs.

But Iyengar quotes Patanjali as frequently as some people quote the Bible, and his new book probes the esoteric depths of human consciousness. Seventy years of rigorous daily asana practice, an intense focus on the body, ultimately yielded the same self-realization achieved by the mental yogis.

This intrigues even athletic guys like David Hufnage, a 49-year-old from Denver who adores the fast pace of power yoga because it really makes him sweat.

“Iyengar yoga isn’t my deal,” says Hufnage, who sports a goatee, shaved head and diamond-stud earring.

“For me it’s a little slow. But from a spiritual standpoint, he’s drawing me in. That’s why I bought his new book.”

The evolution of yoga is the revolution of America, where alternative spirituality sells faster than chakra jewelry.

“What he can do in two seconds would take another teacher two years,” says Nancy Stechert, a senior teacher who founded the Colorado School of Yoga and the International Yoga Center of Tokyo. “He bypasses mind and thoughts to go straight to your soul.”

Like Stechert, Kevin Durkin traveled to India many times to study with the living legend.

“His contribution to the world is quite profound,” says Durkin, who teaches at the Iyengar Yoga Center of Denver.

“Being in the presence of that type of genius is so humbling. Everything he knows about yoga he taught himself from personal experience, with his body as his laboratory. Despite that fierceness in his glance, he’s built the most profoundly knowledgeable system of hatha yoga on Earth.”