If you attain anything at all, it’s conditional, it’s karmic. It results in retribution. It turns the Wheel.

As long as you’re subject to birth and death, you’ll never attain enlightenment. To attain enlightenment you have to see your nature. Unless you see your nature all this talk about cause and effect is nonsense. Buddhas don’t practice nonsense. To say he attains anything at all is to slander a buddha. What could he possibly attain? Even focusing on a mind, a power, an understanding, or a view is impossible for a buddha. A buddha isn’t one sided. The nature of his mind is basically empty, neither pure nor impure. He’s free of practice and realization. He’s free of cause and effect.

The mind’s capacity is limitless, and its manifestations are inexhaustible. Seeing forms with your eyes, hearing sounds with your ears, smelling odors with your nose, tasting flavors with your tongue, every movement or state is all your mind. At every moment, where language can’t go, that’s your mind.

Whoever knows that the mind is a fiction and devoid of anything real knows that his own mind neither exists nor doesn’t exist. Mortals keep creating the mind, claiming it exists. And arhats keep negating the mind, claiming it doesn’t exist. But bodhisattvas and buddhas neither create nor negate the mind. This is what’s meant by the mind that neither exists nor doesn’t exist…

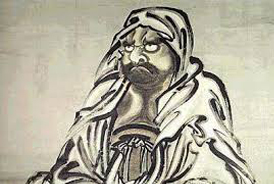

Teachings of Bodhidharma…

Born in 440, Bodhidharma was the youngest of three brothers in the royal family of the southern Indian kingdom of Pallava. His father, the king, was a devoted Buddhist and managed state affairs according to the Buddha’s teachings. He showed his devotion to Buddhism by pious acts such as building Buddhist temples, printing Buddhist sutras, and encouraging his people to practice the Buddhist teachings. The king’s wife constantly donated food and clothes to the poor. All of their efforts helped bring peace and harmony to the state. This environment helped nurture compassion in young Bodhidharma’s heart.

At that time, Prajnatara, the twenty-seventh patriarch of Indian Buddhism, traveled around India preaching the Buddha’s teachings, and one day he arrived in Pallava. The king warmly invited him to the palace, gave him many jewels and precious stones, and prepared a wonderful banquet. After the meal, the king asked Prajnatara to speak to his court.

The monk laid out all the jewels that the king had given him and asked the audience, “Does anyone here know if there exists anything more precious than these jewels?”

The king’s oldest son spoke first. “Dear Master Prajnatara, my ancestor bought that piece of jade in the pile before you with ten castles. I believe that must be the most valuable thing.”

“Those jewels were brought from far, far away,” the king’s second son then said. “Some people even wanted to trade their houses for them, so they are very valuable.”

Many ministers echoed the opinions of the two princes. Then Bodhidharma spoke.

“The most valuable thing is the Buddha’s teachings. These jewels are valuable because they are rare and difficult to come by, but when we die, we no longer own them. The Buddha’s teachings, on the other hand, can help us in life and also free us from constant rebirth after death, so that eventually we can attain buddhahood.”

Everyone in the audience was stunned speechless by Bodhidharma’s words. However, Prajnatara knew right away that Bodhidharma was a remarkable person and that he would be the next patriarch. He asked the king if he could take the young man as his student. The king happily agreed.

From that moment on, Bodhidharma studied under Prajnatara and traveled with his mentor around India to preach the Buddha’s teachings. When Prajnatara passed away, Bodhidharma became the twenty-eighth patriarch of the Chan sect. Just before Prajnatara died, he told Bodhidharma to go and preach in China, where he sensed that Buddhism would become a great religion.

A famous meeting

Bodhidharma sailed to China in 521. When he disembarked at the port city of Canton, he was received with great ceremony by a local official, Shao Ang, who immediately reported Bodhidharma’s arrival to Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty. The emperor ordered the official to accompany the monk to the capital, Chienkang (now Nanking).

Emperor Wu was a devoted Buddhist who had spent a lot of money building temples and duplicating Buddhist scriptures, and he treated Buddhist monks with great reverence. Many government officials followed suit, but they were only playing up to the emperor in the hope of being promoted.

When the Emperor Wu met Bodhidharma, there transpired a now-famous conversation between the two. The emperor spoke to the monk very politely.

“I have built many temples and translated the sutras into Chinese. I have also laid down the rules for people who want to join the ranks of monks or nuns. Furthermore, I have ruled my kingdom in accordance with the Buddha’s teachings. Do I gain any merit from all this? Will I eventually become a buddha?”

Bodhidharma looked at him calmly and replied, “Your Majesty, you have no merit at all.”

The emperor, displeased, asked him, “Why is that?”

Bodhidharma replied, “What Your Majesty has been doing belongs to the merit of Hinayana Buddhism, and you will never be truly freed from endless reincarnation.”

Emperor Wu asked again, “Then what is real merit?”

Bodhidharma answered, “True merit comes from unselfish giving, spiritual cultivation, and dedication to the Buddha and to all living creatures. If Your Majesty can do all this, you will gain true merit.”

The emperor was not happy with this reply or with the monk, and he started to doubt his true identity. In order to find out whether he was really who he claimed to be, Emperor Wu asked Bodhidharma, “What is the first sacred law of Buddhism?”

Bodhidharma replied, “There is no such law in Buddhism.”

Emperor Wu asked very angrily, “Do you know who is standing before you?”

Bodhidharma replied, “No, I don’t.”

What was going on here? Was Bodhidharma out of his mind or was his head still spinning from seasickness after travelling from India to China by boat? No, it was nothing like that. Through their conversation, Bodhidharma knew that Emperor Wu was only interested in gaining merits and attaining buddhahood, but that he had no understanding of the essence of Buddhism. In the end, Bodhidharma left the palace and went north.

As he traveled, he kept hearing talk of Shaolin Temple in Henan Province. The temple had been founded in 496 in honor of an Indian monk named Brahdra, whom Emperor Hsiao Wen of the Northern Wei dynasty had invited to China to preach Buddhism. Bodhidharma had known Brahdra in India, so he decided to go to his temple. Brahdra was delighted to see an old friend and told his students to take good care of him. Bodhidharma meditated before a huge rock in a cave for nine years, in order to find the next patriarch of the Chan sect.

It was the beginning of winter when a monk named Shen Kuang (487-593) came to Shaolin Temple. He sincerely told Bodhidharma that he had been searching for a wise teacher to enlighten him, but the old monk seemed to ignore his plea. Shen Kuang thought to himself that the journey to enlightenment was often full of danger, so how could he leave simply because this great monk ignored him? He decided to stand outside Bodhidharma’s door to show his resolve.

It snowed that night. The snow covered Shen Kuang’s feet, but he just stood there. Eventually the snow piled up to his waist. However, he simply stood there and quietly recited Buddhist scriptures. Bodhidharma had in fact seen Shen Kuang, but he was not sure whether the young man was just another curious visitor. Seeing Shen Kuang standing there in the snow, Bodhidharma was touched and asked, “Aren’t you cold?”

Shen Kuang was a bit surprised to hear Bodhidharma speak to him, but he answered politely, “No, I am not. I am here to learn from you, Master.”

Bodhidharma then asked him, “What do you want to learn?”

Shen Kuang replied, “I want to learn the great compassionate spirit of Buddhism so that I can help the suffering people in the world!”

Bodhidharma tested him by saying, “Well, your vow is very lofty, but I am not sure if you can keep it. You should go do something else, or you’ll be wasting your time and mine.”

Shen Kuang firmly believed he could achieve his goal, so he went back to the temple kitchen, took out a knife, and returned to the cave. There he suddenly chopped off his left hand and placed it before Bodhidharma. The old monk then fully realized how sincere the young monk really was. “You are willing to cut off your hand to show your sincerity and determination. This shows that you can comprehend the Buddha’s teachings. Now I will rename you Hui Ko.”

Hui Ko then applied snow to his wound and wrapped up his injured hand with a piece of his clothing. He then asked Bodhidharma to bring tranquility to his mind. Bodhidharma said to him, “Take out your mind.” Hui Ko realized then that after studying Buddhism for so many years, he still had not comprehended the true meaning of “mind” and did not know where to find it.

At that moment, Bodhidharma shouted at him, “Hui Ko!”

Hui Ko was stunned, but his mind suddenly became completely tranquil. Bodhidharma said to him, “I have brought tranquility to your mind.”

At this, Hui Ko was enlightened and began a new life. News of Hui Ko’s enlightenment spread, and many monks came to Shaolin Temple to ask Bodhidharma to accept them as his students.

The new patriarch

One day, Bodhidharma said to his four main students, “I can sense my days are numbered and there is not much more I can teach you. So, I want you to tell me what you have gleaned from your studies after all these years.”

Tao Fu, the last one to become Bodhidharma’s student, replied first.

“I believe people should not understand Buddhism through words only, because words are simply a means of propagating Buddhism.”

Bodhidharma smiled and said to him, “Tao Fu, you have understood the surface of Buddhism.”

The second student, Tsung Chih, said to Bodhidharma, “My understanding of Buddhism is like Venerable Ananda seeing the Pure Land of the Buddha: you can only see it once, because once is enough to bring enlightenment.”

Bodhidharma nodded his head and said to Tsung Chih, “You have understood the flesh of Buddhism.”

Another student named Tao Yu then said, “The four major elements of the world and we ourselves are always impermanent. Thus, I see no Buddhist teachings.”

Bodhidharma said to Tao Yu, “You have grasped the bone of Buddhism.”

Then, Hui Ko simply stood up, prostrated himself before Bodhidharma, stood up and returned to his seat without uttering a word. Bodhidharma smiled and said to them, “Hui Ko has understood the essence of Buddhism.” Thus, Bodhidharma named Hui Ko the second Chan patriarch of China.

The end

When Bodhidharma named Hui Ko the next patriarch, he was already getting weaker, but he still wanted to return to India. Bodhidharma’s students did not know what else to do, so they decided to accompany him on the journey.

Bodhidharma passed away in 535 in Chien Sheng Temple, Shanhsi Province. His students buried him in Shaolin Temple, while Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty and Emperor Ching of the Eastern Wei dynasty both eulogized the great monk with words of great grief.

However, a strange thing happened after Bodhidharma’s funeral. A messenger named Sung Yun from Eastern Wei was returning from a mission in western China. On his way, he ran into Bodhidharma who, carrying one shoe, was walking slowly toward the west.

Sung Yun was surprised to run into the great monk there, so he asked him politely, “Great Master, where are you going?”

Bodhidharma simply said, “I am going to the west.”

Sung Yun reckoned that since India was to the west, Bodhidharma was probably going home. He did not give too much thought to the matter until he arrived home and learned that the old monk had passed away.

When Emperor Hsiao Ching heard the messenger’s story, he immediately ordered that Bodhidharma’s grave be opened. They found the coffin empty except for one shoe. They realized that Bodhidharma’s reference to the “west” actually meant the Western Pure Land of Amitabha Buddha, and that he was going there to attain buddhahood.