by Megan Larson: The covid-19 virus has brought much attention to the fragilty of this human incarnation…

It has revealed the reality that life is precious, and yet our time on planet earth comes with an expiration tag. For some this has brought questions and fear about mortality, purpose and existence. Children have been watching and trying to make sense of what is happening in the world around them. If they don’t have a framework in which to understand death, it can be a source of great confusion. In my work with families and children this has lately been a major topic: how do we support children in making sense of the great unknown?

Children quickly pick up on our own fears, so our relationship to death is key to how we teach the young and give them a spiritual framework for understanding the nature and meaning of both life and death. It requires us to question our stories and narratives. This requires an examination of our own beliefs and reactions, and how we identify with this infinite sense of I.

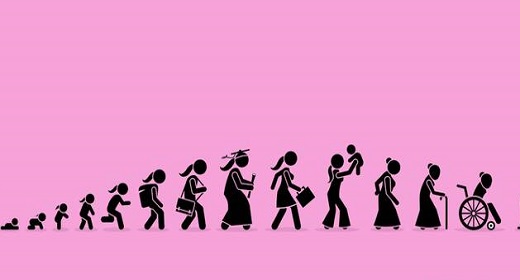

The dominant orientation of Western culture is avoidance of the unknown, which contributes to fear. The way we approach death is the way we experience our life, whether we consider it “the end” or not. In some traditions, such as Tibetan Buddhism, death is contemplated daily as a doorway to awakening and to living fully in each moment. This can open our hearts to living a life of courage, love, compassion, and greater meaning. Teaching children that death is part of the life cycle can shine light on this taboo topic and prepare them for when death touches their lives.

In one of my favorite short stories titled The Fall of Freedie the Leaf, we are walked through Freedie the leaf’s journey, examining his reality and experience of the changing seasons of life. As winter sets in, Freddie says: “I’m afraid to die, I don’t know what’s down there.” His friend comforts him and tells him: “We all fear what we don’t know, Freddie. It’s natural. Yet, you were not afraid when summer became fall. They were natural changes. Why should you be afraid of the season of death?”

Different ages experience a variety of perceptions around death. Children aged three-five, often can’t yet conceptualize, so it can be helpful to discuss the reality of being unable to physically see a person again. At this age they also often engage in magical thinking and may feel they somehow contributed to the death. They may ask questions about “why?” and “how?” death happens. The response of children aged six-eight is based more on self-concern such as how does this affect me. This age can also be fearful that death is something contagious, they are concerned about separation from family or friends. If they directly experience a death they may play out the funeral or service as a way to process.

As they grow older, eight-ten year olds might question the mechanics of death, such as “Does the body hair keep growing after someone dies?” Comparing other’s reactions to death, such as “Why is she crying and you are not?” is very common. They might view death as a punishment for bad behavior, or that it is something they can escape from. Ages 11-14 tend to focus more on moral expectations and questioning about values and beliefs. It is very normal to test faith, even asking: “If the universe is good then why do bad things happen to good people?”

Using nature’s numerous examples of dying, death and renewal processes can be a rich way to expand a child’s perceptions, contemplate the life cycle, and to see the interdependence of all systems and beings together. Collecting dead items from the forest then having a dialogue about them can be a powerful activity. Through nature, children can witness the truth that all living beings on this planet will “die”, thus making room for new living beings to take their place. To illustrate the interconnectedness of all life, take two Aspen trees. At first glance they appear distinct, separate, individual trees side by side. However, each Aspen tree is actually only a small part of a much larger organism. They are completely interconnected underground by their roots, through which they share nutrients and resources to support each other.

As we inquire more deeply, we see that nothing truly exists on it’s own. Everything in life and in nature is connected. An ecological metaphor that stretches our perceptions of ourselves in relationship to the life cycle is in The Lion King. Mufasa, prior to his death, explains to Simba that: “When we die, our bodies become the grass, and the antelope eat the grass, and so we are all connected in the great circle of life.”

We can speak to children about death as a transition that represents an end to the physical that we know, but not an end to the essence. Helping them tune into their hearts enables them to connect with whatever has changed form. Two wonderful books In My Heart and The Invisible Sting illustrate just that. Teaching about interdependence and the life cycle can expand perceptions out of a limited dimensional reality into a much larger one.

Many wise teachers have stated that in denying death, we deny life. Dying is a natural process. Waking up out of the illusion of separation allows us to pass this wisdom to our children. As Thich Nhat Hanh so exquisitely says: “Our true nature is the nature of no birth and no death. Only when we touch our true nature can we transcend the fear of non-being, the fear of annihilation.”

About the author: Megan Larson MSW, LCSW is a psychotherapist, parent coach and mindfulness guide with therapy offices in Colorado & California. She provides parent-coaching & support to clients across the country. Her clinical work is influenced by current research on play therapy, neurobiology, and the mind body connection. As a yoga & meditation teacher, her approach stems from Eastern traditions, specifically Tibetan Buddhism. She is featured in the book The Unexpected Power Of Mindfulness & Meditation along side visionary leaders such as Ed & Deb Shapiro & Byron Katie.

About the author: Megan Larson MSW, LCSW is a psychotherapist, parent coach and mindfulness guide with therapy offices in Colorado & California. She provides parent-coaching & support to clients across the country. Her clinical work is influenced by current research on play therapy, neurobiology, and the mind body connection. As a yoga & meditation teacher, her approach stems from Eastern traditions, specifically Tibetan Buddhism. She is featured in the book The Unexpected Power Of Mindfulness & Meditation along side visionary leaders such as Ed & Deb Shapiro & Byron Katie.

Web site A vibrant Mind LLC