by Maria Popova: “Our neurosis and our wisdom are made out of the same material. If you throw out your neurosis, you also throw out your wisdom.”

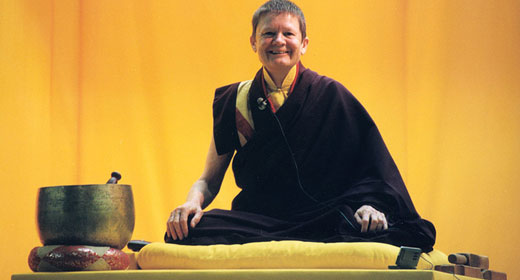

Pema Chödrön (b. July 14, 1936) — a generous senior teacher in the Buddhist contemplative tradition of Shambhala, ordained Buddhist nun, and prolific author — is one of our era’s most tireless champions of a mindful wholeheartedness as the essential life-force of the human experience. For the generations since Alan Watts — who began introducing Eastern philosophy in the West in the 1950s and sparked a counterculture to consumerism seeking to transcend the illusions of the separate self — Chödrön has become the most widely beloved translator of Eastern ideas into Western life.

In the spring of 1989, she led a monthlong dathun meditation session at Gampo Abbey — the renowned Buddhist monastery of which Chödrön is founding director, founded in 1983 by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, her root guru. She began each day by giving a short talk aimed at emboldening participants “to remain wholeheartedly awake to everything that occurred and to use the abundant material of daily life as their primary teacher and guide.” On the monastery grounds, meditators kept five vows: “not to lie, not to steal, not to engage in sexual activity, not to take life, and not to use alcohol or drugs.” The rather singular combination of solitude, nature, meditation, and the vows made for what Chödrön calls “an alternatingly painful and delightful ‘no exit’ situation.” Thus, the collection of her morning talks from the dathun is aptly titled The Wisdom of No Escape and the Path of Loving-Kindness (public library) — short, beautifully simple yet powerful reflections on various aspects of how “to be with oneself without embarrassment or harshness.”

In the fourth talk, Chödrön explores the related graces of precision, gentleness, and letting go:

If we see our so-called limitations with clarity, precision, gentleness, goodheartedness, and kindness and, having seen them fully, then let go, open further, we begin to find that our world is more vast and more refreshing and fascinating than we had realized before. In other words, the key to feeling more whole and less shut off and shut down is to be able to see clearly who we are and what we’re doing.

Pointing to the “innocent, naive misunderstanding that we all share, which keeps us unhappy” — the same well-intentioned but misguided impulse with which we keep ourselves small by people-pleasing — Chödrön writes:

The innocent mistake that keeps us caught in our own particular style of ignorance, unkindness, and shut-downness is that we are never encouraged to see clearly what is, with gentleness. Instead, there’s a kind of basic misunderstanding that we should try to be better than we already are, that we should try to improve ourselves, that we should try to get away from painful things, and that if we could just learn how to get away from the painful things, then we would be happy.

That gentleness of presence, Chödrön argues, is at the heart of meditation:

Meditation is about seeing clearly the body that we have, the mind that we have, the domestic situation that we have, the job that we have, and the people who are in our lives. It’s about seeing how we react to all these things. It’s seeing our emotions and thoughts just as they are right now, in this very moment, in this very room, on this very seat. It’s about not trying to make them go away, not trying to become better than we are, but just seeing clearly with precision and gentleness.

[…]

The problem is that the desire to change is fundamentally a form of aggression toward yourself. The other problem is that our hangups, unfortunately or fortunately, contain our wealth. Our neurosis and our wisdom are made out of the same material. If you throw out your neurosis, you also throw out your wisdom.

Chödrön, however, is careful to point out that holding one’s imperfection with gentleness is not the same as resignation or condoning harmful behavior — rather, it’s a matter of befriending imperfection rather than banishing it, in order to then gently let it go rather than forcefully expel it. Whatever your folly — anger or fear or jealousy or melancholy — Chödrön teaches that freedom from it lies in “getting to know it completely, with some kind of softness, and learning how, once you’ve experienced it fully, to let go.”

And yet, in a sentiment that calls to mind the Chinese concept of wu-wei, “trying not to try,” she gently admonishes against seeing this practice itself as a source of compulsive striving:

Precision, gentleness, and the ability to let go … are not something that we have to gain, but something that we could bring out, cultivate, rediscover in ourselves.

She points to the simple exercise of following your unforced breath as a way of contacting the art of letting go:

Being fully present isn’t something that happens once and then you have achieved it; it’s being awake to the ebb and flow and movement and creation of life, being alive to the process of life itself. That also has its softness. If there were a goal that you were supposed to achieve, such as “no thoughts,” that wouldn’t be very soft. You’d have to struggle a lot to get rid of all those thoughts, and you probably couldn’t do it anyway. The fact that there is no goal also adds to the softness.

This practice, Chödrön points out, cultivates a nonjudgmental attitude and helps us learn how to, instead of succumbing to harsh self-criticism, begin “seeing what is with precision and gentleness” and develop “a sense of warmth toward oneself.” She writes:

The honesty of precision and the goodheartedness of gentleness are qualities of making friends with yourself… As you work with being really faithful to the technique and being as precise as you can and simultaneously as kind as you can, the ability to let go seems to happen to you. The discovery of your ability to let go spontaneously arises; you don’t force it. You shouldn’t be forcing accuracy or gentleness either, but while you could make a project out of accuracy, you could make a project out of gentleness, it’s hard to make a project out of letting go.

In the next talk, titled “The Wisdom of No Escape,” Chödrön explores well-being and suffering as two sides of the same coin which, when put together, define the human condition. She points to the practice of meditation — arguably our greatest gateway to self-transcendence — as the way to illuminate both sides of this duality:

We see how beautiful and wonderful and amazing things are, and we see how caught up we are. It isn’t that one is the bad part and one is the good part, but that it’s a kind of interesting, smelly, rich, fertile mess of stuff. When it’s all mixed up together, it’s us: humanness.

This is what we are here to see for ourselves. Both the brilliance and the suffering are here all the time; they interpenetrate each other. For a fully enlightened being, the difference between what is neurosis and what is wisdom is very hard to perceive, because somehow the energy underlying both of them is the same. The basic creative energy of life … bubbles up and courses through all of existence. It can be experienced as open, free, unburdened, full of possibility, energizing. Or this very same energy can be experienced as petty, narrow, stuck, caught… The basic point of it all is just to learn to be extremely honest and also wholehearted about what exists in your mind — thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, the whole thing that adds up to what we call “me” or “I.” Nobody else can really begin to sort out for you what to accept and what to reject in terms of what wakes you up and what makes you fall asleep. No one else can really sort out for you what to accept — what opens up your world — and what to reject — what seems to keep you going round and round in some kind of repetitive misery.

[…]

This is the process of making friends with ourselves and with our world. It involves not just the parts we like, but the whole picture, because it all has a lot to teach us.

In the remainder of The Wisdom of No Escape and the Path of Loving-Kindness— which shares with Alan Watts’s indispensable The Wisdom of Insecurity not only a similarity of title but also a kinship of spirit — Chödrön goes on to explore such related secular wisdom from the Buddhist tradition as joy, satisfaction, inconvenience, and the art of living with balance in a culture of extremes. Complement it with Sam Harris on the paradox of meditation.