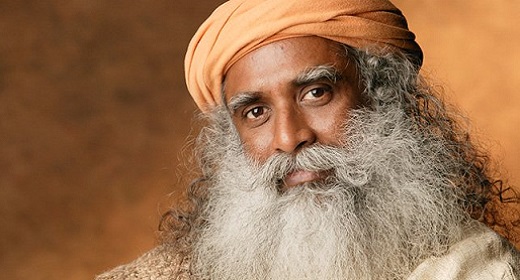

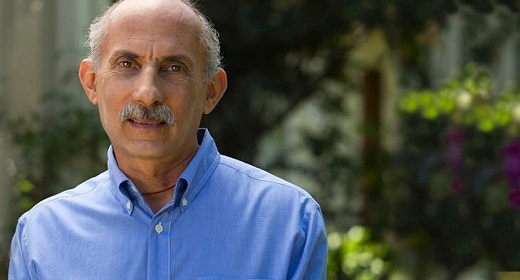

by Jack Kornfield: The following excerpt comes from Jack Kornfield’s newly released book, “No Time Like the Present: Finding Freedom, Love, and Joy Right Where You Are”…

(Simon & Schuster, 2017). In his first major book in several years, the inspiring author of the classic “A Path with Heart”, Jack Kornfield, invites us into a new awareness. Through his signature warmhearted, poignant, often funny stories, with their Aha moments and O. Henry-like outcomes, Jack shows how we get stuck and how we can free ourselves, wherever we are and whatever our circumstances. Renowned for his mindfulness practices and meditations, Jack provides these keys for opening gateways to immediate shifts in perspective and clarity of vision, allowing us to see how to change course, take action, or—when we shouldn’t act—just relax and trust.

Jack recently joined Mindrolling host Raghu Markus for a discussion about trust, freedom and his latest book. The two discuss the uncertain times we find ourselves in as well as how loving-awareness practice can see us through them.

Befriending the Trouble

The good news about these powerful inner forces is that you can use awareness to understand and tame them. When you mindfully recognize your fear, anger, desire, or loneliness, you come to know it, and then it begins to be workable. If you are lonely, for example, study it. The Sufi poet Hafiz warns, “Don’t surrender your loneliness so quickly. Let it cut more deeply. Let it season you as few ingredients can.” If you cannot bear your loneliness, your boredom, your anxiety, you will always run away. The moment you feel lonely or bored, you may open the fridge, or go online, or do anything to avoid being with yourself. But with loving awareness you can endure, honor, and value loneliness and aloneness. And they can be informative. They can teach you about yourself, your longings, what you have neglected for too long. They can help you find a deeper freedom.

Grief is the same. The Lakota Sioux value grief highly; they say it brings a person close to the Great Spirit. When they want to send a message to the other side, they ask a member of a grieving family to deliver it. Whether you feel grief or anxiety, jealousy, addiction, or anger your freedom grows by turning awareness toward it. Zen teacher Myogen Steve Stücky told his friends and students, when he was in great pain, dying of cancer, “I’ve found relief from suffering not by turning away but by turning toward what is most difficult.”

In my own life, I’ve had to learn this with anger. My father was violent and abusive, a wife batterer who dominated all of our family with unpredictable outbursts of rage and paranoia. When he was most abusive, I would run away, and my mother hid bottles behind curtains in every room so she could reach for one to defend herself against his blows.

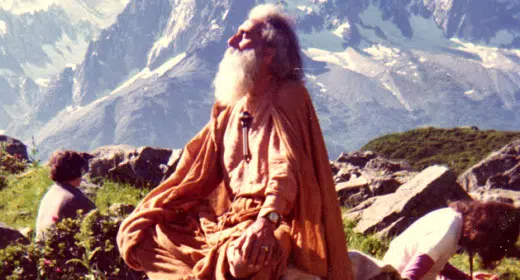

I determined never to be like him. I became the family peacemaker, mediating arguments when I could. So, when I went to live as a young monk in a Thai forest monastery, I thought it would be easy and peaceful. I was unprepared for the intensity of my own restless mind, the uprising of grief, desire, and loneliness I felt. Most surprising was my anger. In not wanting to be like my violent father, I had suppressed all my anger – it had become dangerous to even feel. But in the awareness of meditation and solitude, all the things I was angry about came up. It was more than anger; it was fury. First at my father for being so hurtful to our family. Then, because it frightened me and I had denied it, I was angry at myself for all the times I had suppressed my anger.

Ajahn Chah told me to sit in the middle of it, to wrap myself in robes even on a hot day, and learn to tolerate it. Later my Reichian therapist had me breathe hard, make sounds, shout, grimace, rage, and flail, until I expressed fury’s pain and wept. In these years of meditation and therapy I learned to work with the anger and discovered that it’s an energy that can be known and tolerated, not feared. I had to acknowledge when it was present and realize that I could feel it fully without becoming vengeful or violent like my father.

I also realized that when understood, anger has value. It is a protest when we feel hurt or afraid or when our needs aren’t met. At times, it even brings clarity. The ancient Greeks called anger a “noble” emotion, because it gives the strength to stand up for what you care about most. As I began to understand anger, I could see more clearly the frustration, hurt, and fear that were behind it. My sense of freedom grew as I became more intelligent about it, and slowly its energy was transformed into compassion for myself and others. Now I help others with their emotions as a part of my profession.