By Andrea Thompson: Nearly every person on the planet saw high temperatures that were made at least twice as likely by climate change this summer.

Tourists continually drink water from the fountains in Rome to keep cool during a heat wave that enveloped Europe in August 2023. Credit: Pablo Esparza/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

It has been a grueling summer, with relentless heat breaking multiple records in many places around the world. In fact, June through August was the planet’s hottest documented three-month period, with July ranking as the hottest month ever recorded. A new analysis by the nonprofit organization Climate Central finds that more than 3.8 billion people were exposed to extreme heat that was worsened by human-caused climate change from June through August, and at least 1.5 billion experienced such heat every day of that period. Nearly every person on Earth saw high temperatures that were made at least twice as likely by global warming.

“It really is everywhere,” says Andrew Pershing, Climate Central’s vice president for science. “On a single day, the fact that more than half the people on the planet were experiencing climate-altered heat—that’s just really, really remarkable to me.”

More frequent, longer-lasting and more intense heat waves are among the clearest outcomes of rising global temperatures driven by the burning of fossil fuels. Numerous studies have found the fingerprints of climate change in heat waves from the Pacific Northwest to Europe. A study released by the World Weather Attribution (WWA) research group in July had already found that the heat waves in North America, Europe and China that month were made hotter—and many times more likely—by climate change. In fact, the North American and European events likely would not have occurred without climate change.

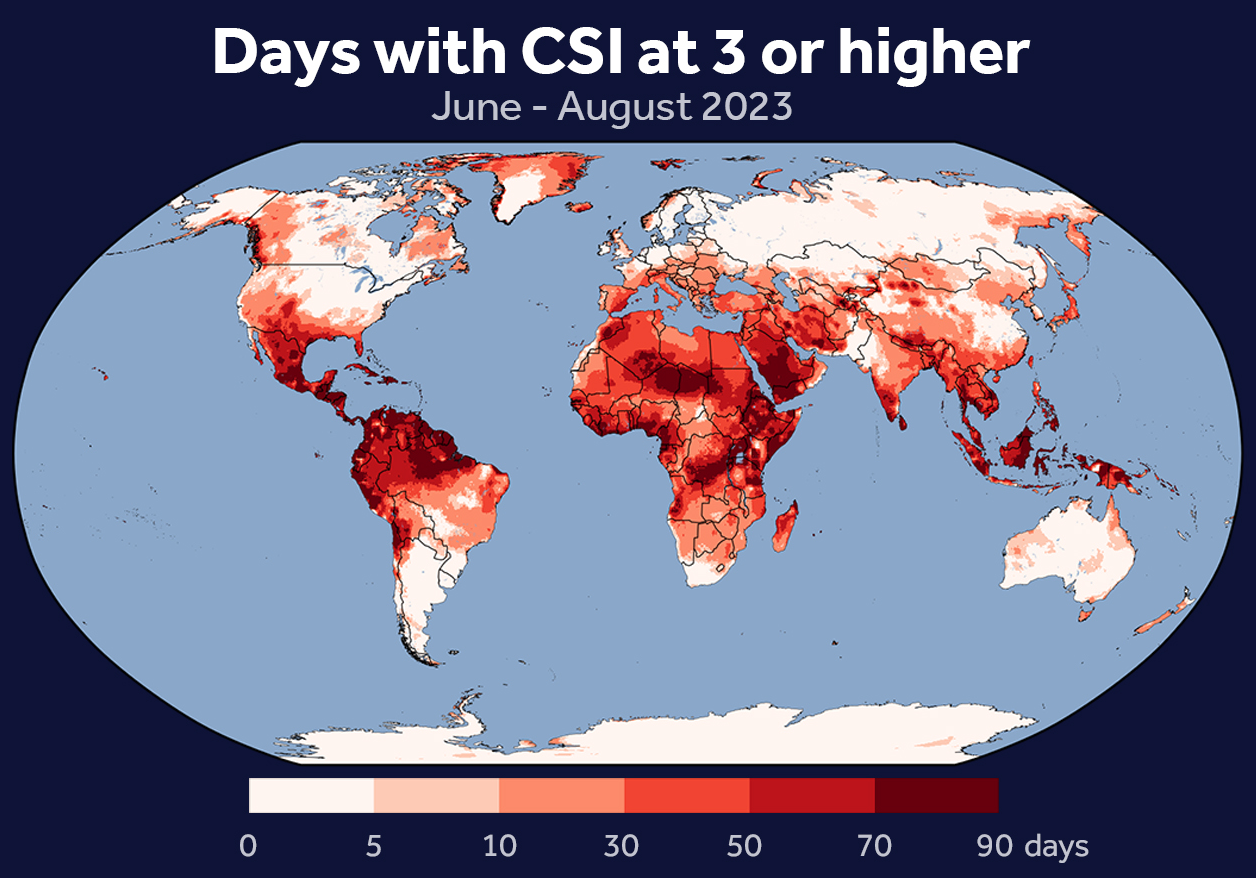

The new analysis was produced using Climate Central’s Climate Shift Index (CSI) attribution system, which estimates how much climate change has shifted the local odds of events such as extreme heat. The system, which is based on peer-reviewed science, scores global warming’s influence using the ratio of how often a given temperature occurs in the current climate, compared with a world without climate change. A CSI of 1 means there is a discernable influence from climate change, and CSIs between 2 and 5 mean it made those conditions two to five times more likely.

The organization’s worldwide temperature analysis during this year’s Northern Hemisphere summer found 48 percent of the world’s population experienced at least 30 days of extreme heat that was made at least three times more likely by climate change, and at least 1.5 billion people experienced heat at that level or higher for the entire summer. Many of those people were in areas closer to the equator, such as the Caribbean, northern Africa and Southeast Asia.

Heat at a CSI of 3 or higher was present for at least half the summer in a total of 79 countries in Central America, the Caribbean, the Arabian Peninsula and Africa. On August 16, 4.2 billion people experienced extreme heat at these levels.

The persistence of the heat was one aspect that particularly struck Pershing. “Places around the world that have really just gotten locked into these records,” such as Phoenix, Ariz., he says, “they had day after day after day where they were at level 5.”

Extreme heat is a major health risk—it is the deadliest type of weather in the U.S. by far. And it is particularly hazardous for people who lack access to air-conditioning or reliable sources of clean water, those who work outside, the very young, the elderly and those with existing health problems, particularly heart disease.

“In every place, if you start to push it beyond the temperatures that people experience on a regular basis, that’s dangerous heat because you’re not prepared for it physiologically. You’re not prepared for it in terms of your infrastructure,” Pershing says. This happens even in tropical areas where heat is common, such as Puerto Rico—just a small shift above average temperatures there can have a large impact on people who are acclimated to a stable climate, said Friederike Otto, a climate scientist at the Grantham Institute–Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London, during a press briefing on Thursday. Otto is involved with the WWA.

Many of the people who face such conditions are from areas that have contributed the least to global warming. Climate Central’s analysis found that countries with the lowest historical greenhouse gas emissions levels experienced three to four times as many days with a CSI of 3 or higher, compared with G20 countries, the world’s 20 largest national economies.

The G20 is meeting this weekend in India. At the briefing, Otto said that as long as these countries continue to burn fossil fuels and subsidize the fossil fuel industry, “they kill their populations; they kill the vulnerable populations in the world. We have to stop burning fossil fuels.”

It is clear this summer is a harbinger of things to come. Not every summer will be as hot as this one, but today’s record summer heat will be the average in a few decades. “This is not a problem that’s going to go away,” Pershing says. “We know it’s going to get worse.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andrea Thompson, an associate editor at Scientific American, covers sustainability. Follow Andrea Thompson on Twitter Credit: Nick Higgins