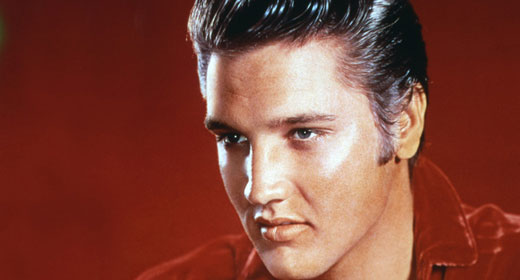

by Gary Tillery: To Elvis’s frustration, no one in his life other than Larry Geller could appreciate his spiritual quest.

The Memphis Mafia had no interest in any departure from the status quo. They resented Geller for ruining a good thing and stealing time and attention that used to belong to them. They referred to him sarcastically as the Swami, Rasputin, and, because he was Jewish, Lawrence of Israel. They wouldn’t hesitate to use the terms in front of Geller, but never in Elvis’s hearing.

Colonel Parker saw him as a threat. The money machine he had constructed was humming along quite nicely. Why did Geller have to distract Elvis from important things—the things that kept the machine humming? Discounting that Geller’s motives might be well intentioned and innocent, and no doubt subscribing to the notion that it takes one to know one, he concluded that the hair stylist was using his access to manipulate Elvis by psychological trickery. He considered the whole “religious kick” nothing other than the result of mind control, and he summoned Elvis to his MGM office to tell him so. When Elvis wouldn’t listen to reason, the Colonel persuaded the Mafia foreman, Joe Esposito, to report to him secretly on the state of Elvis’s psychological health. As soon as Elvis became aware of the betrayal by one of his own, he immediately fired Esposito.

Priscilla also criticized Elvis’s spiritual pursuits—and to his face. She became exasperated by his constant efforts to draw her into his strange new world. Wanting to attend the lectures given by Manly Palmer Hall, but knowing his presence would be disruptive, Elvis encouraged Priscilla to go in his place. She “found the lectures difficult to understand and painful to endure.” She kept trying to take an interest because it was so important to him. She considered Elvis her soul mate and wanted to please him. But one of the ways he wanted to “cleanse” himself and grow more spiritual was to overcome temptations of the flesh—and Priscilla craved intimacy with him. The more firmly he committed himself to the life of the spirit, the more estranged she became.

During the filming of Harum Scarum Elvis was delving into Autobiography of a Yogi, which, along with The Prophet and The Impersonal Life, became one of his favorite books. It relates the life story of Mukunda Lal Ghosh, an Indian mystic who became famous under his religious name, Paramahansa Yogananda. Even as a boy Yogananda felt drawn to the spiritual life and searched for the proper guru. At seventeen he linked up with Swami Yukteswar Giri, a master of Kriya Yoga. The swami had amazing abilities, which he demonstrated for Yogananda over the years, including the power to materialize in more than one place at the same time. He himself had been initiated into Kriya Yoga in 1884 by Lahiri Mahasaya, a holy man who in 1861 had been tasked with reintroducing the ancient discipline to the world by an enigmatic figure Lahiri called Babaji. A simple accountant for the government, Lahiri had been out walking in the foothills of the Himalayas one day and had a “chance” encounter with Babaji. After speaking with him for a while, Lahiri had the odd feeling that he had known the reclusive figure before—and finally recognized him as his guru in previous incarnations. In time he would conclude that the mysterious Babaji was actually an avatar of Lord Krishna.

After several days of instruction from Babaji, Lahiri returned to his home and devoted the rest of his life to the spread of Kriya Yoga. Unlike many holy men, he advised most of his disciples to continue their daily lives exactly as before. For him, living in an enlightened state did not require renunciation of the world and being an ascetic. He made no distinction between Hindu, Muslim, Christian, or Jewish followers and was as welcoming to those of the lowest caste as he was a maharajah.

Yogananda became an adept at Kriya Yoga and traveled to the United States in 1920. He represented India that year at the International Congress of Religious Liberals. Except for a world tour in 1935–36, he remained in the U. S. for the rest of his life. He founded the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) in 1920 and established its headquarters in Los Angeles in 1925. He lectured widely and spread knowledge of Hindu beliefs and the benefits of Kriya Yoga wherever he went. In 1946 he published his autobiography, which included the stories of many holy men and the powers they displayed—amazing powers such as clairvoyance and levitation.

Elvis was impressed by Yogananda’s tales and also by the universalism of his approach. One day, on a break during the filming of Harum Scarum, he looked up from reading the book and informed Larry Geller that he thought he was ready for initiation into Kriya Yoga. To the stunned Geller, this was much like saying he thought now would be a good time for the Pope to name him a cardinal. Geller knew how demanding the training was because he had been through the two-year program himself. The first step was a yearlong regimen of daily physical exercises, health consciousness, and a stipulated schedule of meditation.

Nevertheless, Geller called the SRF headquarters in Los Angeles and made arrangements for Elvis to speak with its head, Sri Daya Mata. As Faye Wright, of Salt Lake City, she had become a disciple of Yogananda in 1931 and had worked closely with him until his death in 1952. She quickly agreed to meet with the King of Rock and Roll, and the next evening, after the day’s filming, Elvis and Geller went to the SRF ashram on Mount Washington.

Elvis loved the sylvan setting, and he had an immediate rapport with Daya Mata. In her features and demeanor she reminded him of his mother. The more she described the aims of the Fellowship, the more excited he became. He said he was ready to turn his back on his career and join a monastery or start a commune. She advised him to go slow—that his development must be evolutionary. They discussed the process of training and meditation, and she gave him her personal lesson books to study. He accepted them gladly, but he had the unbridled enthusiasm of the novice. “This higher level of spirituality is what I’ve been seeking my whole life,” he told her. “Now that I know where it is and how to achieve it, I want to teach it. I want to teach it to all my fans—to the whole world.”

Over the coming months he returned to the site often for solace. He read and meditated, but like most seekers he hoped for a short path to his goal, and it did not come. The cosmos did not care that he was Elvis Presley. He kept coming back nevertheless, and he also liked to visit the Fellowship’s fourteen-acre retreat by the ocean in Pacific Palisades, where Yogananda had written most of his autobiography. (George Harrison, another admirer of Yogananda, also liked to visit the retreat when in Los Angeles.)

Daya Mata stressed that the goal of Yogananda’s teachings was to establish harmony between a person’s spirit, mind, and body. Elvis made a sincere effort to meditate and transform himself according to her suggestions. He kept looking for signs that he was developing special powers, and as time went on there was evidence that he was succeeding.

He once took George Klein aside on the grounds at Graceland. Elvis directed his attention to some bushes, then placed his hand over them and held it steady. In a moment the bushes started to move. Then Elvis told him to look up at a particular cloud. He began to gesture with his hands and, to Klein’s surprise, the cloud seemed to move as well. Although he retained some skepticism, thinking it might have been his own imagination, Klein never forgot the incident.

Priscilla was convinced that Elvis had a healing touch. “He was capable of spiritual healing, one touch of his hands to my temples and the most painful headaches disappeared.” So was Jerry Schilling, who had spent two weeks in a hospital after a motorcycle accident and had begun to worry that he would never be able-bodied afterward. Though he refused to think of it as anything mystical, the nagging pain did leave while Elvis was treating him. Elvis’s grandmother Minnie Mae was also convinced, and she allowed Geller and her famous grandson to treat her arthritis and other ailments over the years.

Sonny West acknowledged Elvis’s belief in his capabilities, although he was dubious about the capabilities themselves: “Elvis announced that he possessed psychic healing powers and could cure the common cold or other ailments through his simple touch. He also thought he could make leaves move and turn the sprinkler system of the Bel Air Country Club on and off through telekinesis.” However, years later, when West’s infant son had a high fever, Elvis asked if he could come and pray over him. He donned a turban and placed the child on a green scarf and began to pray while making circular motions over him. The boy’s temperature soon dropped to below 100 and did not go up again. West admitted that he and his wife were “amazed.”

More impressed still was an anonymous bus driver on the side of the road near Nashville. Gripped by severe chest pain, he had curbed his vehicle and staggered off. Elvis, passing by, ordered his own driver to stop and rushed to the man. He put one arm around his shoulders and placed the other on his heart, reassuring him. Moments later the man was fine, though astonished to be helped personally by Elvis Presley. After making sure an ambulance was on the way, Elvis climbed back into his own bus and moved on.

As part of his spiritual training, Elvis liked to go outside in the middle of the night and spend hours watching the movement of the planets. He felt that there were waves of energy moving the planets through the universe and that with proper attunement they could be seen. One night he saw a UFO. He pointed it out to Sonny West, who at first thought it might be an airplane or helicopter. But the vehicle made no sound. They watched its approach through tree limbs as it passed over the house toward the front lawn. Elvis told Sonny to go get Jerry Schilling so he could see it, too. When the two came bounding out the front door, Elvis was nowhere to be seen. For a moment they worried that he had been abducted. Then they noticed him three doors away, staring toward the south, where the craft had disappeared.

Geller gave Elvis a book about the subject. A week later, just after he had finished reading it, Elvis and some of the group were driving through New Mexico on Route 66. They saw a bright disk streaking across the dark sky, descending. Suddenly it stopped and made a right-angle turn, accelerating until it disappeared from view. Elvis said, “That was definitely not a shooting star or a meteor. It was clearly something different.” Jerry Schilling commented, “We don’t make anything that moves like that.” Geller voiced what they were thinking, “That object maneuvered like a flying saucer.”

Still later, Elvis witnessed a UFO one evening at Graceland while in the company of his father. The eerie experience prompted Vernon to reminisce about the blue light he had seen the night Elvis was born in Tupelo.

In the mid-sixties the quest for mind expansion generally led, sooner or later, to experimentation with drugs. Priscilla recalled that she and Elvis tried marijuana several times, but neither cared for it. They both responded by growing “tired and groggy,” and the well-known side effect of ravenous hunger caused them to gain weight they did not want.

After reading Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception and Timothy Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience, Elvis did try LSD—but just once. He first persuaded Red and Sonny West to try it in Los Angeles, with Larry Geller, Charlie Hodge, and himself watching the whole time to make sure they were safe. Then he and Priscilla tried it a few months later during his Christmas break at Graceland. They invited Geller, Lamar Fike, and Jerry Schilling to accompany them on their trip, while Sonny West was appointed to keep an eye on them.

They started by sitting around a conference table in Elvis’s upstairs office. After a while they saw each other’s faces distorting and broke into laughter. Priscilla witnessed her husband’s multicolored shirt grow larger and larger, spreading out so far that it seemed ready to burst. After about ninety minutes they stood up to stretch and realized that Jerry Schilling had somehow disappeared. They searched and found him under a pile of clothes in Elvis’s closet. Then they became fascinated by a large aquarium containing two or three fish, which appeared to them as an ocean teeming with fish.

After a while Priscilla broke into tears. She dropped to her knees in front of Elvis and said, “You really don’t love me. You just say you do.” She then accused Larry and Jerry of not liking her, and called herself ugly. Eventually, that mood passed. The movie The Time Machine came on television. Elvis became fascinated by it. He asked for a pizza and spent most of the trip eating, while watching the film and observing his fellow trippers.

At dawn they went outside. The rising sun created rainbows in the moist air that left them dazzled, and they examined dewdrops on the leaves. Then they got down on the lawn to inspect individual blades of grass. They could see the veins, and they watched the grass breathing slowly, in and out. They told each other how lucky they were to be such friends. The experience fascinated Elvis and Priscilla, but they found LSD much too powerful and neither tried it again.

Elvis’s ability to sample and disregard marijuana and LSD no doubt reinforced his own feeling of mastery over such temptations. As a rule he detested drug use. He often expressed amazement that Hank Williams had died of an overdose. He found it incomprehensible that someone so intelligent and successful could fall prey to drugs. Yet the sad irony is that even in the midsixties he was starting a slide toward the same fate. He was blind to the process because his drugs came in the form of legal medications prescribed for him by doctors. He also suffered under the typical addict’s delusion that he could take or leave the medication—that he had the willpower to stop whenever he chose.

Among the leaders in the push for mind expansion in the sixties were the Beatles. (“I’d love to . . . t-u-r-r-n . . . y-o-u-u . . . o-n-n.”) By August 1965, both John Lennon and George Harrison had already begun spiritual quests of their own. Both had experienced the mellowing effects of marijuana, and both had tried LSD.

Elvis and the Beatles occupied the apex of the music world, sharing a level all their own. While the Beatles were on tour in the United States in August 1965, Brian Epstein extended feelers to Colonel Parker about a meeting. All four of his boys idolized Elvis, and he was the only public figure they were anxious to meet. When the band came to Los Angeles to appear at the Hollywood Bowl, Epstein and Parker worked out details to bring them together.

The encounter took place on the evening of Friday, August 27. At 10:00 p.m., three limousines carrying the Beatles and their entourage showed up at the gate of Elvis’s home on Perugia Way in Bel Air. Elvis awaited them on the long sofa in his living room. John and Paul sat down beside him on one side, Ringo on the other. George Harrison took a place on the floor where he could face Elvis.

The conversation started off awkwardly. Nervous about coming face to face with their idol, the Beatles had smoked some marijuana on the way to his house. Now they were as daunted to be in his presence as their own fans were to be in theirs. Elvis finally broke the spell by saying, “Look, guys, if you’re just going to sit there and stare at me, I’m going to bed.”

They started talking about the color television in the room. Color programming had not yet come to Britain. Elvis had a bass guitar close at hand and began to play along with a song on his jukebox, “Mohair Sam,” by Charlie Rich. He offered the others instruments, and soon they started jamming to “You’re My World,” “Johnny B. Goode,” and the Beatles’ own “I Feel Fine.” With no drum set, Ringo soon gave up thumping on the sofa and went to shoot pool with some of the Mafia.

George eventually wandered off and went outside to light up a joint. Larry Geller went to search for him, and they discussed Indian religion and philosophy. Eventually Elvis led them all out to the garage to show them his new Rolls-Royce, and on the way they were spotted by hundreds of fans gathered at the front gate. That provoked competing chants of “Elvis! Elvis!” and “Beatles! Beatles!” Finally, the Beatles left about 2:00 a.m.

The five would never meet again, although Ringo visited Elvis during his Las Vegas performances, and John Lennon spoke with him by phone several times during the seventies about Lennon’s troubles with the US government.

Over the coming months Elvis delved into numerology, the science of numbers. It intrigued him, for example, that seven shows up so frequently in religious symbolism—seven heavens, seven thrones, seven seals, seven churches, etc. He became fascinated by the Greek philosopher Pythagoras, who, five centuries before Jesus, had founded a university based on the esoteric aspects of mathematics. Geller brought him a copy of Cheiro’s Book of Numbers. It joined The Impersonal Life, The Prophet, and Autobiography of a Yogi as one of the most-consulted books in his library.

Cheiro was the professional name of an Irishman born William Warner. He spent time in India as a young man and claimed to have studied an ancient book on palmistry while there and mastered its lessons. He returned to Europe and became a palmist, telling the fortunes of such notables as Mata Hari, Oscar Wilde, Thomas Edison, and Mark Twain.

While primarily known for palmistry, Cheiro also published texts on astrology and numerology. Cheiro’s Book of Numbers first appeared in 1926. In it he showed how a person’s name and date of birth could be used to derive a number that gave essential information about that individual’s character and fate. The number also dictated which days of the month were favorable or unfavorable for activities.

Elvis, according to the book, was an eight. He was fascinated to recognize himself in Cheiro’s descriptions of “eight” individuals:

“These people are invariably much misunderstood in their lives and perhaps for this reason they feel intensely lonely at heart. . . . They have deep and very intense natures, great strength of individuality; they generally play some important role on life’s stage, but usually one which is fatalistic, or as the instrument of Fate for others. . . . One side of the nature of this number represents upheaval, revolution, anarchy, waywardness and eccentricities of all kinds. The other side represents philosophic thought, a strong leaning towards occult studies, religious devotion, concentration of purpose, zeal for any cause espoused and a fatalistic outlook colouring all actions.”

Elvis found it intriguing that James Dean and Peter Sellers, both of whom he greatly admired, were eights. He also found it significant that both he and Colonel Parker were eights. Furthermore, his astrological sign was Capricorn, and the Colonel was a Cancer—exact opposites on the zodiac. Elvis saw this as indicative that they represented different polarities. After all, his turf was the creative end while the Colonel’s was business.

Another book he found entrancing was The Initiation of the World, by Vera Stanley Alder. She discusses the Great White Brotherhood—the enigmatic group revealed to our time by Helena Blavatsky and other Theosophists—spiritually advanced figures who are secretly directing the development of humankind. According to Larry Geller, Elvis came to believe that he was carrying out his role in the world under the guidance of these masters, one of whom was Jesus.

He also became fascinated by esoteric meanings in his own name. “Elvis” was such an exotic name—where did it come from? With Geller’s help, he found that “El” traced back to ancient times, a cross-cultural phoneme that conveyed the meaning of light, or shining, and was used in Hebrew, for instance, to connote God. (Think of Beth-El—“House of God,” and Elohim, the plural of God.) And “Vis” had the meaning of the power of God.

The discovery of a connection with Hebrew held deep significance for Elvis—for reasons he wouldn’t divulge to Geller (or anyone else) until the year of his death. He began to wear a chai pendant, the Jewish symbol for living and life, in addition to his customary cross. (When a reporter asked him about the strange juxtaposition, he quipped, “I don’t want to be kept out of heaven on a technicality.”) He donated $12,500 toward a fund to build a Jewish community center in Memphis. And one day he took Geller with him for a visit to his mother’s gravesite. Without offering any explanation, he made the comment that he planned to place a Star of David on her memorial stone next to the cross already there.

Meanwhile, he kept working on his film career. Frankie and Johnny turned out to be a cut above the other films he had made recently. As a pleasant bonus, he found that his director, Frederick de Cordova, and costar, Donna Douglas, enjoyed engaging in philosophical discussions during the downtime. Douglas—not at all like her most famous character, Elly May Clampett in The Beverly Hillbillies—was actually an intelligent and spiritual woman. She impressed Elvis even more when she told him she was a member of the Self-Realization Fellowship and knew Daya Mata very well.

He also made a spiritual connection with Deborah Walley, his costar in Spinout, filmed and released in 1966. A lapsed Catholic, she admitted, “I was not on good terms with God. It was a void of not feeling one way or the other.” Elvis gave her rides on the back of his Harley and invited her to his trailer every day for lunch, where they had profound conversations. “We talked about Buddhism, Hinduism, and all types of religion. He taught me how to meditate. He took me to the Self-Realization Center and introduced me to . . . Yogananda.” Elvis seemed anxious to share with her the new vistas that had opened up for him, and felt so comfortable that he cast aside all inhibitions about revealing himself. “I’m not a man,” he told her, “I’m not a woman—I’m a soul, a spirit, a force. I have no interest in anything of this world. I want to live in another dimension entirely.” Walley was just as anxious to ingest what he had to say. “In a kind of odd way, Elvis was a guru to me, and I was a very eager pupil.” She considered the encounter with Elvis the turning point of her life.

Fortuitously, RCA encouraged Elvis to make his next album a religious one. His first gospel album, His Hand in Mine, had fared reasonably well on its release in 1960. One of the songs recorded during the session, “Crying in the Chapel,” had been held back for release as a single. Unexpectedly, the wait extended until 1965. However, when it was finally issued for Easter that year, the record performed surprisingly well, peaking at number three on the pop charts. Acknowledging that success, and with his soundtrack albums increasingly disappointing in sales, RCA decided to capitalize on Elvis’s well-known spirituality.

The project reinvigorated him. He personally selected every song, carefully scrutinizing those submitted to him by his music publisher, Hill and Range, and those by his good friends Red West and Charlie Hodge, as well as sifting through his own vast collection of gospel records. He wanted every song on the album to be special. He saw the project as a way to reach people, to convey his own deep love of God to everyone who listened. He exercised great care in selecting his backup singers, inviting his old friends the Jordanaires, as well as a new all-star quartet put together by Jake Hess, his childhood idol. With the inclusion of three female singers, he built a chorus of eleven—a potent gospel force.

Those who were there at the recording sessions realized that something extraordinary was going on. When Elvis sang the title track, “How Great Thou Art,” Jerry Schilling was stunned. “When he got to the dramatic finish of the song, there was a strange hush in the room—nobody wanted to break the spell. I’ve been in a lot of recording studios since my time with Elvis, but I’ve never seen a performer undergo the kind of physical transition he did during that recording. He got to the end of the take and he was as white as a ghost, thoroughly exhausted, and in a kind of trance.”

From the vibrant, up-tempo “So High” and “By and By” to the meditative “I Come to the Garden Alone” and the deeply reverent and achingly gentle “Farther Along,” Elvis created a masterpiece of sound and spirituality. The album earned him his first Grammy, for Best Sacred Performance of 1967.

Much more important than any industry award was the impact the album had on the lives of listeners. Years later, Larry Geller was walking through the lobby of a hotel in St. Petersburg, Florida, where Elvis was due to give a concert. Someone called to him to say hello, a woman of about twenty-five. He recognized her as one of the fans who traveled from city to city, following Elvis on his tours. Curious to understand their passionate attachment to him, he asked her why. The answer startled him: “That’s simple: he saved my life. And now it’s his.” Even more curious now, he escorted the woman to the coffee shop to chat.

He learned that she was an epileptic. During one episode, she had tumbled down a flight of stairs and injured her lower back. She began to suffer excruciating pain that no medicine seemed to relieve. One night she decided she could no longer endure such a life. She spread out sleeping pills on a nightstand and wrote a note to her family, explaining her decision. Taking a final look around the room, she became aware that the radio was still on and reached over to turn it off. Just as she did, Elvis came on, singing “How Great Thou Art.” The profound reverence of his voice pierced her soul and uplifted her. “It was the way he sang it. All the love of God seemed to come through him. . . . I felt the courage flow back through my body, and with it the will to live. . . . There and then, I vowed to dedicate my life to Elvis, to help and protect him.”

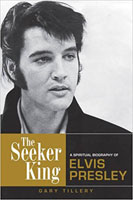

©2013 by Gary Tillery.

This material was reproduced by permission of Quest Books, the imprint of the Theosophical Publishing House, from The Seeker King: A Spiritual Biography of Elvis Presley.