Donna Quesada: I would like to talk more about what your practice is, and how those practices helped you in your situation.

But first, Chögyam Trungpa… I mean, what a privilege to have been raised in a household that held him you know, as their guru, as their teacher, and to be able to call him your teacher from such a young age. He’s quite a well-known teacher, and I you know, having read his books myself, I also am personally curious what that was like. And I’d love whatever stories you can share, what your memory is, of having known him, or studied under his guidance, under his tutelage, as a child. That is fascinating. What an honor.

Kiri Westby: I think it is. For me, it was a very privileged upbringing, not just that I was in the west and had food and shelter and whatever kind of material needs I wanted… I had two loving parents in a loving household. But this idea that we were taught meditation, starting at the age of, I guess, formally the age of six, but I started painting even younger than that in our preschools.

So, in addition to Chögyam Trungpa, there was a whole community of his devotees and other Tibetan Buddhist teachers who were coming to Boulder and helping to create this brand new experimental community in which the children, myself and others I know… there’s about 400 of us… that were born into this community… were raised in private Buddhist schools.

So, we were taught the dharmic arts of bana and calligraphy and haiku and meditation, of course, and just raised in a very specific way, in which… It wasn’t until I was older, maybe eight or nine years old, that I realized that the world wasn’t Buddhist. I thought, you know, maybe there were a few non Buddhists out there in the world… I didn’t quite realize that we were the ones who were kind of quite different, in the context of the United States of America and Colorado.

And so I think, what was it like… Trungpa was sort of well-known for just dropping in on the children in school and getting down on the ground and playing with us and I have memories of sitting in his lap and he used to say it’s so refreshing to just be with the children because they have this beginner’s mind. They don’t have any concept of like… my parents and my friends’ parents had come from a Judeo-Christian background, and they had different concepts of things like Original Sin and deep, deeply ingrained concepts that we were never taught, and never had, as part of our, sort of… understanding of who were in the world.

And how refreshing for him it was to be around that bright, beginning kind of mind, nothing to undo… just to kind of like, help us be young little warriors in the world. And we were trained very specifically on a path of warriorship and asked to really look at the suffering in the world and then to consider how we wanted to spend this lifetime trying to alleviate some of that suffering.

DONNA: Beautiful. Well, you’re using a Zen expression, Beginner’s Mind. That’s actually my background… in Zen.

KIRI: And so, Trungpa… Suzuki Roshi… Beginner’s Mind was also around a lot as we were children, and we learn, always chill. Well, from Sensei, who’s the Imperial bow maker to the Emperor of Japan, and there was a lot of Zen and Japanese traditions folded into our childhood and Trungpa had a lot of reverence for the dharmic arts in Japan that were so well honed… calligraphy and what not, that we were taught as children.

DONNA: I wondered when you mentioned haiku! Well, the Tibetan situation has always been one of the issues that I personally care a lot about. And I’ve tried to spread awareness, you know, about what has been going on there, to my own students. And so, for that reason also, I’m just so glad to have you share your story. And I’d like to talk to you more about how learning meditation at such a young age, how that served you during this ordeal. But just to give a little more context to your story, so that whoever’s listening would have an idea of how dire your situation was… Could you just describe a little bit about the events leading up to your capture?

KIRI: Yeah, definitely. So I had been working as a human rights activist for many years, at this point… it was 2007. And I was contacted by a group of activists that I knew through Greenpeace and Rainforest Action Network and something called the Ruckus Society, that were highly dedicated to nonviolent direct action, using non violence and creative big profile ways, to draw attention to causes. So, I was contacted by a group that I knew peripherally, that told me they had learned that the Chinese government was going to be hosting their first Olympic Games in 2008. And they had spent decades trying… bidding to get an Olympics, and they had a billion dollars to finally win the International Olympic Committee and even activists had spent decades working against them… even having the right to hold the Olympic Games.

And eventually, they just took it to the nth degree. They were going to use this platform, the most watched televised event in the world, to really legitimize their authoritarian rule in different places around the world. They were going to do the most ambitious torch relay route around the whole world that had ever been done. They were going to take the torch to the top of Mount Everest in occupied Tibet, which had never been done and in scientifically… keep a flame burning at 29,000 feet. They went really big with the sort of propaganda plan.

And so, in that activist… we learned that they were going to do a trial run. You can only summit Everest for about two weeks in April, especially on the north face, which is the Tibet side of the mountain. There’s two ways… there’s also the Nepal side… you can summit, but they learned that this Chinese expedition team was going to be doing a trial run to get the torch to the top of Mount Everest. An activist said we have to be there.

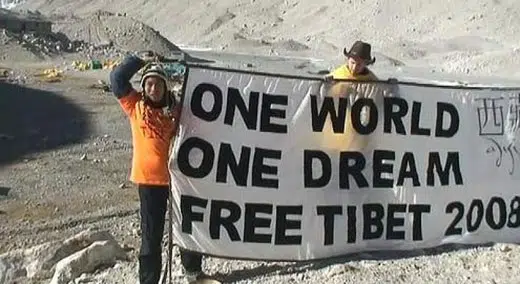

This is a moment when the whole world is going to be watching China on Tibetan soil… the base of what Tibetans consider one of their holiest mountains, Mt. Oomolangma in Tibet, is Mount Everest in English, and they have one of their oldest monasteries at the base of that mountain, and activists said, we’re not going to let them sort of sports wash the occupation of Tibet — we’re not going to let them sit around and cheer.

And so, when I was contacted by activists, they had been planning for a long time. They had been planning to try to figure out how they were going to get inside Tibet. And the idea was to get a Tibetan, an exile Tibetan, or Tibetan American inside Tibet to raise his voice in protest. A really incredibly difficult thing to do. And so, because I have been smuggling information and money across more zones for a long time, I was sort of known in this group as somebody who… and I had been to Tibet. I was married in Tibet… as somebody who might be able to leverage my vast amounts of privilege and knowledge and try to help a Tibetan American get to Mount Everest and raise his voice.

My plan was to remain anonymous and keep my name and my face out of the news for the whole thing. I used an alias for that reason, as we moved across the country. But once we were actually arrested, and our names got out, that was sort of the end actually, of 10 years of working anonymously. But we managed to get Tenzin Dorjee back into Tibet and successfully launched a protest, and we did it at Basecamp.

And on Everest, right there in in front of the Chinese expedition team… It also was the 18th birthday of the Panchen Lama, who is the youngest political prisoner in the world, and he and his family were kidnapped when he was six years old. Because he technically or traditionally is the one who would find and verify the next Dalai Lama… And the Chinese government felt if they kidnapped him, then perhaps there could be another Dalai Lama who’s become a sort of spiritual and political leader of the Tibetan cause… And so they had always said to the international community that they were holding him for his own safety and that he was fine, and that he was a child… And so, this was his 18th birthday and it was like… No longer did he fall into the protection of the Chinese government vote that morning.

A lot of amazing kind of almost miraculous things had to come together for us to actually… three different groups to actually meet at the same spot at the right moment, to get the camera equipment working at 19,000 feet in subzero degrees, and to successfully launch a protest and simultaneously broadcast it out of the Chinese firewall to a computer in New York City. So, it was a very ambitious plan. Nobody thought we could do it. We ourselves many times didn’t think we could do it. The test the day before, had failed. None of the batteries on the equipment were working because of the cold. And actually, one of our technical engineers spent the entire night awake with a little fire… burning chips of Yak dung to boil water to put into our Nalgene bottles to put inside our sleeping bags, to put the satellite inside, with the hope that it would stay warm enough to send the signal out… because it was our only security measure… to have this video because even with the video for day, the Chinese government denied having arrested us, or disappeared us, and a huge international incident occurred, but the video was proof, so the video was sort of known. It was really an important piece.

And many things converged on this beautiful morning on the Panchen Lama’s birthday and we decided we were going to change our protest and throw him a bit of a birthday party in the wake of all… the Chinese expedition climbers and turns in Georgia. We built a torch out of a butterfly. And we were Team Tibet. Jerseys. And he raised his voice and raised the lamp high and he sang the Tibetan national anthem, which we believe was the first time it had been recorded and broadcasted for almost 50 years. Wow. Across the board… it just had to happen in that moment.

We had to be there. So many obstacles had to be overcome to get us there. And yet we all felt like we had some kind of magic on our side and so many prayers from so many people to make it happen and five young, in our 20s, nonviolent Americans with nothing other than our passports and a sign and our own creativity. Basically, we stole the Olympic spotlight from the Chinese government and we circumvented millions of dollars and decades of planning and in one sort of creative, non-violent moment change, the whole conversation around China hosting the Olympics, and then things went sideways. Yeah, I mean at first, interestingly, the military who are posted at Everest Base Camp for the Chinese government are primarily ethnically Tibetan.

They can live genetically… can live longer at really high altitudes—they’ve evolved to do that—compared to the Chinese, from lower altitudes, and it’s kind of I think, considered sort of a low on the totem pole post, to be sitting at some jail at Everest Base Camp, wondering if anything’s going to happen.

So guys who arrested us were as much in shock as anybody, that we had even shown up that morning and done this protest. And what were we thinking? And initially, they were actually, you know, quite gentle and kind with us, I thought. Well, they held us for a short period of time… we’re only eight hours from the Nepal border. And they’ll drive us down and kick us out of the country and try to kill this as fast as possible. That would have been the smart political move, but they did not do that. Instead, they helped us at gunpoint at Space Camp for about 14 hours.

And then the Chinese Secret Police arrived and they were wearing full uniforms and sunglasses at 11 o’clock at night and they were not messing around and they started by immediately separating us and searched us and started in on some pretty intense torture tactics. Each of us sort of handled it a bit differently, but then they took and drove us through the night for 12 hours or so with multiple stops in different police stations where they would pull one of us out, and there was a lot of confusion and fear happening at that point. I was sort of caught up in it, thinking this was going to be the end of my life, and the adrenaline was so overwhelming that I started getting very sick and I started throwing up, and we they stopped the car at one point. I thought they would just let me kind of lean my head out of the car and vomit. But instead, they pulled me like 300 feet from the car and to the cliff…

DONNA: Yeah, remember the scene… I couldn’t believe it.

KIRI: Yeah, so in that moment, I was sure I was going to die. And I have been told by many Tibetans in exile that that happens a lot. There’s an incident, or an arrest, and then in the light of day, not everybody shows up at the police station. Some people are just tossed over cliffs or just disappeared in route. And so, I figured that was going to be my fate. Instead… I think it was still part of just an intense intimidation campaign and they were laughing at me as I was vomiting, and had peed myself, and was on the ground thinking I was gonna die. And it was all part of this kind of like… torture tactics. To kind of get us to try to open up to them about who we were and what we were doing.

But yeah, so there were parts of the idea that were terrifying. And then we just talked about, like as soon as I didn’t die, and the worst case scenario didn’t happen… All of a sudden… all the fear just kind of lightened and went away. And I was able to drop into the meditation that I had been taught in my lifetime. I was able to find some kind of ground. And even from that point, if we got sentenced to life in a labor camp… I was still alive. And so, when you compare it to witnessing your own death in this moment, everything afterwards was easier.

Read and Watch Part III Here: Awaken Interviews Kiri Westby – Pt 3 – The Medicine Of Listening

Read and Watch Part IV Here: Awaken Interviews Kiri Westby Pt 4 – Waking Up To Something Bigger Than Ourselves

Read and Watch Part I Here: Awaken Interviews Kiri Westby Pt 1– Awakening Is Refusing To Be Deluded Into a World of Just Light

Kiri Westby: From inside an interrogation session with the Chinese Secret Police, a young American activist recounts her path into global human rights work — exploring critical lessons on privilege and compassion in the context of war and extreme suffering.

When I was arrested by the Chinese military for launching a historic Tibetan Freedom protest, I knew every trial and lesson had been worth it — even if it meant facing a life in prison.

When I was arrested by the Chinese military for launching a historic Tibetan Freedom protest, I knew every trial and lesson had been worth it — even if it meant facing a life in prison.

After a childhood infused with esoteric Buddhist teachings, I was forged into a global activist through years of witnessing and collaborating in the dissent of women on the front lines of war. From villages in Nepal, to refugee camps in The Democratic Republic of Congo, to the streets of Bogota, Colombia, my initiation into human rights activism was raw and transformative. The bravery of those women bolstered me in my darkest hours of interrogation and torture by the Chinese Police, and it guides me now to share my true story—no matter the repercussions. This is not a tale the Chinese government wants told.

During my years working in war zones, I often wondered if I’d have the courage to stand up to tyranny, to lay my life on the line to confront undeniable persecution.

In 2007 — on the slopes of Mt. Everest — I found out.

Take a literary journey with me as I reveal the bumpy road I took to becoming my bravest self — learning to leverage a life of advantage, find a place for my own joy, and cultivate the courage needed to play a distinct role in history.

Buy it Here: Fortune Favors the Brave