by Victoria Dawson: Psychologist and longtime meditation teacher Tara Brach discusses why self-compassion is more essential for our well-being than ever…

To find Tara Brach on a summer Saturday morning is to follow a path that seems to naturally ease one into a state of mindfulness. From the multi-lane Capital Beltway that girds Washington, DC, one exits with relief onto a two-lane, tree-lined byway where streetlights are few and commercial strips nil. Eventually, the road narrows to a single lane, announced by a row of mailboxes and shrouded heavily with trees. Stillness and quiet prevail. Soon, a steep driveway delivers the visitor into a sunny glade with a modest, window-rich house. With the ringing of a doorbell and the barking of a dog, Tara Brach, meditation teacher and author, appears.

Brach, who worked as a clinical psychologist for 16 years, is the author of three books: Radical Acceptance, True Refuge, and the just-released Radical Compassion. Her podcasted talks and meditations often originate in her well-attended Wednesday night meditation and class, held in Bethesda, MD, and in the half-dozen retreats that she offers annually. She and fellow teacher Jack Kornfield are cofounders of the Awareness Training Institute (ATI), which offers online courses on mindfulness and compassion, as well as the Mindfulness Meditation Teacher Certification Program. Brach is also the senior teacher and founder of Insight Meditation Community of Washington, DC. She has taught classes to staffers in the US Senate, and, beginning in February 2020, she will offer teachings in the House of Representatives.

Let’s start with coming home—from travel, from the city, from other excursions—to this property where you live and work, nestled in the woods.

The closer I get to home, the more trees I see, and my nervous system starts to calm down. I’m privileged: My home is a sanctuary that allows me to call on what feels deepest and most true.

And you live near the Great Falls section of the Potomac River—an area of stunning natural beauty.

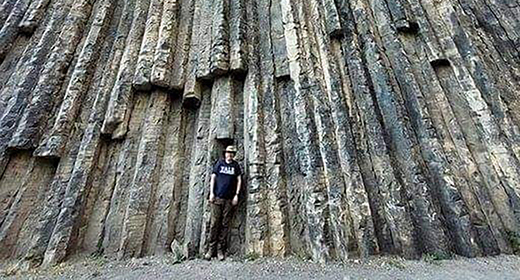

I begin each day by going to the river with my dog, kd. It’s a short walk from my house to a park, where I follow a trail, with ups and downs, for about three miles, through the woods, along a stream, to the river, which is strewn with beautiful rocks—you can actually see the bones of the earth in the river. Being physical and in nature takes me out of the habitual circling of my thoughts. A lot of the material for my talks—pieces, stories, illustrations—comes as I’m walking along the river.

Do you have a formal meditation practice that incorporates that setting?

Depending on the weather, I’ll meditate by the river for half an hour or when I return home. The meditation itself involves coming into stillness, a kind of collecting and quieting. And then it becomes a practice of being—letting whatever arises be, just as it is. There’s always a current of sensing into loving awareness, whether through prayer or self-compassion or offering loving-kindness to others.

You mention self-compassion, which brings us to the topic at hand: your new book, Radical Compassion. As your third book, where does it fit in the arc of your work?

My motivation in writing my first book, Radical Acceptance, was a revelation that I’d been living in this trance of unworthiness—living in a constricted world with a preponderance of stories about a self who was failing or deficient or flawed, and all the fear and shame that went with that. I began to see how mindfulness and compassion could wake me up out of that story.

The inquiry was how to use mindfulness and compassion when we hit these big life difficulties that catapult us into a reactive trance.

In a similar way, when I wrote True Refuge, I had been struggling with illness—a connective tissue disorder—and a downward spiral, with no sense I would recover and have my life back. So, my trance then was the narrowed identity of “sick person,” and filled with anxiety and grief about loss. The inquiry was how to use mindfulness and compassion when we hit these big life difficulties that catapult us into a reactive trance.

On the worst days of your illness, what was life like for you?

When I hit real lows, my joints were inflamed, and between pain and exhaustion, the most I could do was walk slowly around my house. When this went on for a stretch of days, I’d get depressed—grim and irritable. My meditation practice became very challenging and deep. Over and over, I had to face the raw vulnerability of loss, fear, and grief. And, with that, my heart became more compassionate. I increasingly found a refuge in loving presence, which felt more the truth of who I was than an identity of “sick person.” This awakening gave rise to writing True Refuge, and in a daily way, helped me become more intelligent about coping.

And you’re better?

Much, much better. The key has been to listen and become more truly embodied—qigong helped. I had to learn how not to injure myself and how to build back enough muscle strength to help stabilize my joints. I’m hiking and swimming now, and I’m grateful for every day that I can enjoy moving on this earth.

Do you find that healing and self-compassion interrelate in some way?

A palliative caregiver describes the greatest regret expressed by the dying: I didn’t live true to myself. To “live true” we need to awaken self-compassion and love ourselves into healing. And we need to attune to others with an active caring, and include all beings in our heart.

Why is self-compassion so essential?

Compassion arises when we experience suffering, and to experience suffering directly we need to be in touch with vulnerability in our body, where the suffering registers. Then the natural response is tenderness. Self-compassion then allows us to feel compassionate toward others: If we have not been with our own vulnerability, we cannot resonate with another person’s vulnerability.

How can compassion be “radical”?

What I call “radical compassion” is a mature, fully evolved expression of compassion, grounded in an embodied, mindful presence. There’s a movement to help, and it’s all-inclusive. That is, it’s not feeling compassion for one person but then being completely shut off, for example, from a politician whose policies or ideology I disapprove of. Radical compassion is an all-embracing tenderness.

There’s a teaching that’s very relevant to me: Somebody goes in the woods and sees a little dog and they go over to pet the dog and the dog lunges at them with its fangs bared. Instead of feeling friendly, the person pulls away into anger. But then the person sees that the dog’s leg is caught in a trap. As soon as they see it, everything shifts. It’s like, oh, you poor thing. Now, they don’t get close again because the dog still could bite them, but their heart is relating differently.

Did the desire to write about compassion also spring from a sense of distress about the troubled times we live in?

Most of us would say the world is increasingly divided, hostile toward those who are different or who think differently from us. There is a rampant sense of “unreal other”—of not experiencing the other as a real being. If someone is an “unreal other” then we can violate them.

We can sustain the sense of “unreal other” only as long as others are at a distance, but as soon as we bring an intentional, meditative lens to them, bring them close into →our psyches, we sense their vulnerability. To heal the separations, we need to be with each other, talk with each other, and get to know each other.

How does this play out in your daily life?

I habitually get stuck in a sense of needing to do more, checking things off the list, being anxious about the next presentation or the next class. As I’m speeding around, I’m cut off from my body and my heart. I’m more inclined toward silly mistakes, my memory is not as good, I’m less sensitive to the world. I lose contact with my deepest nature. When that happens, I notice it and bring “light” RAIN (see page 48) to it: I recognize and allow that, OK, this is my speedy, anxious, doing self, trying to accomplish more, trying to control reality. I investigate, feeling the vulnerability underneath: that vague sense that I’m going to fail. If I can touch that, put my hand on my heart, and tell myself it’s OK, then a profound shift into compassionate presence occurs. I can re-enter the activity without the clench of anxiety, opened to a larger sense of who I am.

When you look back, what aspects of your childhood strike you as foundational to your life’s work?

I had a fortunate balance of blessings and sufferings. In that sense, I lucked out. My parents were loving and they paid attention to me. I didn’t experience trauma, and I had a pretty decent sense of belonging. My father was both a hard-driving person and a dedicated do-gooder. I received the message of “Always be more, do more” and “Be better,” so I had all the suffering of “never enough.” My mother was an alcoholic, so I inherited addictive tendencies and shame about that.

My parents also had a strong ethic of serving that led me to pay attention to other people and what was going on with them. Somehow, I felt I was part of something bigger and valued serving into that.

And my parents loved nature. They sensed the mystery and loved the beauty of the earth. I remember a family camping trip in the Blue Ridge Mountains when, early one morning, I was sitting on a rocky ledge, looking out and feeling awe, feeling at one with nature and knowing that this mattered. This was way before I knew the word “meditation.”

Now, you’re in your mid-60s and newly a grandmother. What do those six decades add up to, for you?

A lot of grace. The arc has been one of increasing trust in awareness and in love—knowing these are more the truth of who I am, who we are, than any personality. And that trust brings more ease with and compassion for the conditioning that plays through these bodies and minds of ours. The realization brings freedom and peace and joy.

Can you think of an example of how that realization plays out for you?

Some years ago, I had a falling out with another teacher, who was also a friend. It was a painful breakup—mistrust, hurt, misunderstanding, and enough reactivity that we were unable to reconcile. On the ego level, each of us felt wronged. We were both committed to mindfulness, and this rift felt like a real failure. My inner practice became one of not buying into my judgments, either about him or about myself—not believing the judgments about who was right or wrong, good or bad. I was able to keep an awareness of his vulnerability and my vulnerability and, ultimately, our goodness. That wasn’t easy. The more I could keep from buying in to the frame of right and wrong, the more freedom I found to see a deeper truth. This truth included that it’s possible to make peace when things don’t work out the way we think they should. Stuff always happens, and that frame of right and wrong freezes us, prevents us from learning and growing. So, holding a larger frame and understanding that it’s OK that we did not reconcile, allowed me over time to hold him with benevolence.

You sound just as prone to the pitfalls of humanity as the rest of us!

I encounter the same old challenges of judging myself and getting anxious about things and so on. I used to get stuck in a grim or hurting or reactive place for days; now it’s minutes or an hour before I realize what’s going on. The grip is not as great. I don’t believe my thoughts and when I’m stuck, there’s a natural turning toward presence and compassion. I’ve practiced a lot—many rounds. It’s sometimes called “many glimpses”: The more you glimpse who you are beyond the story, the more you trust it.