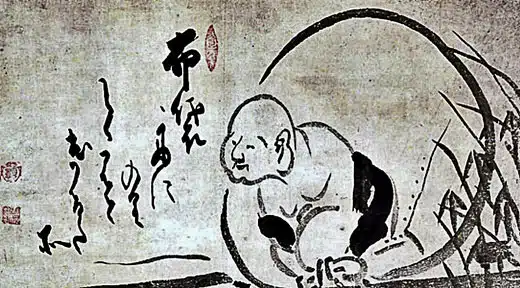

Donna Quesada for Awaken: Firstly, it is with a deep bow that I thank you for spending this time with us today.

Your writings were a deep source of inspiration for me personally, when I was a young student of Zen, and I am thrilled to share your story with our readers and with those who are curious about this discipline. One of the features of Zen that makes it very unique is the Koan—those esoteric stories or statements that serve as meditation devices. We might even say that Koan work is the core of authentic Zen practice… Would you share with us your first assignment with a koan?

Your writings were a deep source of inspiration for me personally, when I was a young student of Zen, and I am thrilled to share your story with our readers and with those who are curious about this discipline. One of the features of Zen that makes it very unique is the Koan—those esoteric stories or statements that serve as meditation devices. We might even say that Koan work is the core of authentic Zen practice… Would you share with us your first assignment with a koan?

Zen Master Hakuin: When we arrived at the Shōju-an hermitage, I received permission to be admitted as a student, then hung up my traveling staff to stay. Once, after I had set forth my understanding to the master during dokusan [personal interview], he said to me, “Commitment to the study of Zen must be genuine. How do you understand the koan about the Dog and the Buddha Nature?” “No way to lay a hand or foot on that,” I replied. He abruptly reached out and caught my nose. Giving it a sharp push with his hand, he said, “Got a pretty good hand on it there!” I couldn’t make a single move, either forward or backward. I was unable to spit out a single syllable.

That encounter put me into a very troubled state. I was totally frustrated and demoralized. I sat red-eyed and miserable, my cheeks burning from the constant tears. The master took pity on me and assigned me some koans to work on: Su-shan’s Memorial Tower, The Water Buffalo Comes through the Window, Nan-ch’üan’s Death, Nanch’üan’s Flowering Shrub, The Hemp Robe of Ching-chou, Yün-men’s Dried Stick of Shit. “Anyone who gets past one of these fully deserves to be called a descendant of the Buddhas and patriarchs,” he said.

Awaken: I have experienced a taste of how perplexing it can be to work on a koan, as any rational explanation will be waved away. Did you continue to feel demoralized, or did it just make you more determined?

Hakuin: A great surge of spirit rose up inside me, stiffening my resolve. I chewed on those koans day and night. Attacking them from the front. Gnawing at them from the sides. But not the first glimmer of understanding came. Tearful and dejected, I sobbed out a vow: “I call upon the evil kings of the ten directions and all the other leaders of the heavenly host of demons. If after seven days I fail to bore through one of these koans, come quickly and snatch my life away.” I lit some incense, made my bows, and resumed my practice. I kept at it without stopping for even a moment’s sleep. The master came and spewed abuse at me. “You’re doing Zen down in a hole!” he barked. Then he told me, “You could go out today and scour the entire world looking for a true teacher—someone who could revive the fortunes of ‘closed-barrier’ Zen—you’d have a better chance finding stars in the midday skies.”

Awaken: Did you still feel that he was he the best teacher for you?

Hakuin: I had my doubts about that. “After all,” I reasoned, “there are great monasteries all over the country that are filled with celebrated masters: they’re as numerous as sesame or flax seed. That old man in his wretched ramshackle old poorhouse of a temple—and that preposterous pride of his! I’d be better off leaving here and going somewhere else.”

Awaken: I also recognize that strict approach that your master had adopted, to spur you on! And it worked, I suppose… because despite your vexation with him, you continued on. Were you able to penetrate the koan?

Hakuin: Early the next morning, still deeply dejected, I picked up my begging bowl and went into the village below Iiyama Castle. I was totally absorbed in my koan—never away from it for an instant. I took up a position beside the gate of a house, my bowl in my hand, fixed in a kind of trance. From inside the house, a voice yelled out, “Get away from here! Go somewhere else!” I was so preoccupied, I didn’t even notice it. This must have angered the occupant, because suddenly she appeared flourishing a broom upside down in her hands. She flew at me, flailing wildly, whacking away at my head as if she were bent on dashing my brains out. My sedge hat lay in tatters. I was knocked over and ended heels up on the ground, totally unconscious. I lay there like a dead man.

Neighbors, alarmed by the commotion, emerged from their houses with looks of concern on their faces. “Oh, now look what the crazy old crone has done,” they cried, and quickly vanished behind locked doors. This was followed by a hushed silence; not a stir or sign of life anywhere. A few people who happened to be passing by approached me in wonderment. They grabbed hold of me and hoisted me upright. “What’s wrong?” “What happened?” they exclaimed.

Awaken: What had happened in the midst of that tussle?

Hakuin: As I came to and my eyes opened, I found that the unsolvable and impenetrable koans I had been working on —all those venomous cat’s-paws—were now penetrated completely. Right to their roots. They had suddenly ceased to exist.

Awaken: It had enkindled an awakening experience?

Hakuin: I began clapping my hands and whooping with glee, frightening the people who had gathered around to help me. “He’s lost his mind!” “A crazy monk!” they shouted, shrinking back from me apprehensively. Then they turned heel and fled, without looking back. I picked myself up from the ground, straightened my robe, and fixed the remnants of my hat back on my head. With a blissful smile on my face, I started, slowly and exultantly, making my way back toward Narasawa and the Shōju-an. I spotted an old man beckoning to me. “Honorable priest,” he said, addressing me, “that old lady really put your lights out, didn’t she?” I smiled faintly but uttered not a word in response. He gave me a bowl of rice to eat and sent me on my way.

Awaken: You must’ve rushed to share this news with Master Shoju!…

Hakuin: I reached the gate of Shōju’s hermitage with a broad grin on my face. The master was standing on the veranda. He took one look at me and said, “Something good has happened to you. Try to tell me about it.” I walked up to where he was standing and proceeded to explain at some length about the realization I had experienced. He took his fan and stroked my back with it. “I sincerely hope you live to be my age,” he said. “You must firmly resolve you will never be satisfied with trifling gains. Now you must devote your efforts to post-satori training. People who remain satisfied with a small attainment never advance beyond the stage of the Shravakas. Anyone who remains ignorant of the practice that comes after satori [sudden enlightenment] will invariably end up as one of those unfortunate Arhats… Their rewards are paltry indeed.

Awaken: As I would’ve expected… he didn’t want to congratulate you, but rather keep you humble so that you continue your practice. What exactly did he mean by Post-Satori training?

Hakuin: By post-satori training, he means going forward after your first satori and devoting yourself to continued practice —and when that practice bears fruit, to continue on still further. As you keep on proceeding forward, you will arrive at some final, difficult barriers. What is required is simply “continuous and unremitting devotion to hidden practice, scrupulous application—that is the essence within the essence.”

Awaken: But you moved on in your travels after that point, didn’t you? Were you able to continue to train in the same way?

Hakuin: After we took our leave from Shōju, my companions and I pressed on and for several days, traversing difficult stretches of rugged terrain where the trail wound along towering mountain cliffs. After a long, arduous journey, we at last crossed into our home province. I went straight to Nyoka Rōshi’s bedside and began ministering to his needs. Even as I nursed him, I complied faithfully with the injunction Shōju had given me when we parted at the foot of the mountains. Never for a moment was I remiss. Regularly and without fail, I sat for eight incense sticks of zazen each night.

Awaken: Did you have any more Satori experiences?

Hakuin: While crossing over the mountainous country of Echigo and Shinano Provinces on the trip back, and on into southern Suruga, I experienced satoris both great and small, in numbers I could not even count. Unfortunately, shortly after that the heart fire, unbeknownst to me, began to rush upward, oppressing my lungs and parching them of their essential fluids. Before I knew it, I had developed an incurable disorder of the heart.

Awaken: Oh no… that must’ve been very disheartening and it must’ve made traveling very difficult, not to mention practicing!

Hakuin: I began moping around in a dark, melancholy state. I was always nervous and afraid, weak and timid in mind and body. The skin under my arms was constantly wet with perspiration. I found it impossible to concentrate on what I was doing. I sought out dark places where I could go to be alone and just sat there motionless like a dead man. Neither acupuncture, moxacautery, nor medical potions brought me any relief. I was ashamed to return and show my face at Shōju’s in my present state. I wanted to comb the country and search for a wise teacher who might be able to offer some cure for my condition.

But I couldn’t leave the master’s sickbed, even for a short time. I tried praying to the gods and Buddhas, but that didn’t do any good either. As I was cudgeling my brain trying to come up with a way out of my predicament, a wonderful thing happened. A younger brother of mine—a monk named Hatsu happened to hear about Nyoka Rōshi’s illness. He made the long trip all the way from the Kantō district and asked to take over the task of caring for the master. Overjoyed at this unexpected turn of fortune, I received the master’s consent to leave, then quietly gathered my belongings into a travel pack and left the temple. My destination was the town of Yamada in Ise Province. My pretext for going was a lecture-meeting on the Record of Hsi-keng to be given by Jōsan Oshō.

Traveling with Spurring Students through the Zen Barrier as my constant companion, I stopped off several times to visit noted Zen teachers along the way. I told them of the trouble I was having and asked them for assistance, but they all said the same thing: I was suffering from “Zen sickness,” and there was nothing they could do for me. The last stop I made was to see old Egoku Oshō in Izumi Province.

Awaken: What did he say?

Hakuin: “Attempting to cure Zen sickness,” he told me, “only makes it worse. Find the quietest, most secluded spot you can. Settle down there [and do zazen] with the intention of withering away together with the mountain plants and trees. You mustn’t spend the rest of your life running all over the country looking for someone to help you.”

Awaken: Didn’t this turn out to be the most intense post-Satori work you had ever thrown yourself into?

Hakuin: Despite Egoku’s advice, because I wanted to be close enough to have occasional interviews with him, I made for the Inryō-ji, a Sōtō temple in nearby Shinoda, and put up for a while in their Zen Hall. There were at that time, more than fifty men in residence in the hall. The seat next to mine was occupied by a monk named Jukaku Jōza. Jukaku was a superior monk who had a genuine aspiration for the Way. We found our minds to be in complete agreement. I felt as though we had known each other for many years.

On one occasion, the two of us engaged in a private practice session. We pledged to continue it for seven days and nights. No sleep. No lying down. We cut a three-foot section of bamboo and fashioned it into a makeshift shippei [bamboo staff, connoting authority]. We sat facing each other with the shippei placed on the ground between us. We agreed that if one of us saw the other’s eyelids drop, even for a split second, he would grab the staff and crack him with it between the eyes. For seven days, we sat ramrod-straight, teeth clenched tightly in total silence. Not so much as an eyelash quivered. Right through to the end of the seventh night, neither one of us had occasion to reach for that cudgel.

Awaken: Unbelievable dedication! Did you finally have another breakthrough?

Hakuin: One night, a heavy snowfall blanketed the area. The dull, muffled thud of snow falling from the branches of the trees created a sense of extraordinary stillness and purity. I made an attempt at a poem to describe the joy I felt:

If only you could hear

the sound of snow

falling late at night

from the trees

of the old temple

in Shinoda!

About that time, the abbot of the Inryō-ji took me aside and told me that he wished to have me stay on at the temple as his successor. The temple holdings included some very rich and productive fields, making it possible to provide for forty or even fifty visiting monks at annual summer retreats. Uppermost in my mind at the time was a trip to Hyūga in Kyushu to visit Kogetsu Rōshi, so I found it difficult to come to a final decision.

Shortly after, I obtained permission to leave the temple and struck out on my own for Kyoto. Jukaku slipped away from the assembly, walked along at my side for several leagues, and then turned back. I was soon overtaken by a violent rainstorm. The water poured in sheets, turning the road to thick mud, which sucked at my ankles as I walked. But I pushed forward into the mist and pelting rain oblivious to it all, humming as I went. All at once, I found I had penetrated a verse that I had been working on, Master Ta-hui’s “Lotus leaves, perfect discs, rounder than mirrors; Water chestnuts, needle spikes, sharper than gimlets.”

It was like suddenly seeing a bright sun blazing out in the dead of night. Overcome with joy, I tripped, stumbled, and plunged headlong into the mud. My robe was soaked through, but my only reflection was, “What’s a muddy robe, compared to the extraordinary joy I now feel?” I rolled over onto my back and lay there motionless, submerged in the mire.

Awaken: This sounds just like your first breakthrough experience in Shoju!

Hakuin: It was a repeat performance of the events that had taken place some years before in Iiyama… Some other travelers happening by rushed up and stared with amazement and alarm at the figure lying dead in the mud. Hands grabbed at me and propped me up. “Is he unconscious?” they cried. “Is he dead?” someone asked. When I returned to my senses, I began clapping my hands together with delight and emitting great whoops of laughter. My rescuers started backing away from me with doubtful grins on their faces. Then they broke and ran, yelling “Crazy monk! Crazy monk… I had just experienced one of those eighteen satoris I mentioned before. I resumed my journey, stepping buoyantly down the road with a blissful smile on my face. I was plastered with mud from head to foot but so happy I found myself laughing and weeping at the same time. Although in no hurry to reach my destination, before I knew it, I was walking the streets of the capital.

Awaken: That must have been quite a spectacle! I would like to go back to the Zen sickness… was that still plaguing you, and how did it come about?

Hakuin: On the day I first committed myself to a life of Zen practice, I pledged to summon all the faith and courage at my command and dedicate myself with steadfast resolve to the pursuit of the Buddha Way. I embarked on a regimen of rigorous austerities, which I continued for several years, pushing myself relentlessly. Then one night, everything suddenly fell away, and I crossed the threshold into enlightenment. All the doubts and uncertainties that had burdened me all those years suddenly vanished, roots and all—just like melted ice.

Deep-rooted karma that had bound me for endless kalpas to the cycle of birth-and-death vanished like foam on the water. It’s true, I thought to myself: the Way is not far from man. Those stories about the ancient masters taking twenty or even thirty years to attain it—someone must have made them all up. For the next several months, I was waltzing on air, flagging my arms and stamping my feet in a kind of witless rapture. Afterward, however, as I began reflecting upon my everyday behavior, I could see that the two aspects of my life—the active and the meditative—were totally out of balance. No matter what I was doing, I never felt free or completely at ease. I realized I would have to rekindle a fearless resolve and once again throw myself life and limb together into the Dharma struggle.

With my teeth clenched tightly and eyes focused straight ahead, I began devoting myself single-mindedly to my practice, forsaking food and sleep altogether. Before the month was out, my heart fire began to rise upward against the natural course, parching my lungs of their essential fluids. My feet and legs were always icecold: they felt as though they were immersed in tubs of snow. There was a constant buzzing in my ears, as if I were walking beside a raging mountain torrent. I became abnormally weak and timid, shrinking and fearful in whatever I did. I felt totally drained, physically and mentally exhausted. Strange visions appeared to me during waking and sleeping hours alike. My armpits were always wet with perspiration. My eyes watered constantly. I traveled far and wide, visiting wise Zen teachers, seeking out noted physicians. But none of the remedies they offered brought me any relief.

Awaken: So discouraging… but you found the strength to carry on. Did you finally encounter someone who could help you regain your health?

Hakuin: Then I happened to meet someone who told me about a hermit named Master Hakuyū, who lived inside a cave high in the mountains of the Shirakawa District of Kyoto. He was reputed to be three hundred and seventy years old. His cave dwelling was two or three leagues from any human habitation. He didn’t like seeing people, and whenever someone approached, he would run off and hide. From the look of him, it was hard to tell whether he was a man of great wisdom or merely a fool, but the people in the surrounding villages venerated him as a sage. Rumor had it he had been the teacher of Ishikawa Jōzan and that he was well versed in astrology and deeply learned in the medical arts, as well.

Awaken: He sounds almost mythical! And he was a real recluse, I heard. Please share more about your adventures in finding him…

Hakuin: People who had approached him and requested his teaching in the proper manner, observing the proprieties, had on rare occasions been known to elicit a remark or two of enigmatic import from him. After leaving and giving the words deeper thought, the people would generally discover them to be very beneficial. In the middle of the first month in the seventh year of the Hōei era [1710], I shouldered my travel pack, slipped quietly out of the temple in eastern Mino where I was staying, and headed for Kyoto.

On reaching the capital, I bent my steps northward, crossing over the hills at Black Valley [Kurodani] and making my way to the small hamlet at White River [Shirakawa]. I dropped my pack off at a teahouse and went to make inquiries about Master Hakuyū’s cave. One of the villagers pointed his finger toward a thin thread of rushing water high above in the hills. Using the sound of the water as my guide, I struck up into the mountains, hiking on until I came to the stream. I made my way along the bank for another league or so until the stream and the trail both petered out. There was not so much as a woodcutters’ trail to indicate the way.

At this point, I lost my bearings completely and was unable to proceed another step. Not knowing what else to do, I sat down on a nearby rock, closed my eyes, placed my palms before me in gasshō [in prayer], and began chanting a sutra. Presently, as if by magic, I heard in the distance the faint sounds of someone chopping at a tree. After pushing my way deeper through the forest trees in the direction of the sound, I spotted a woodcutter. He directed my gaze far above to a distant site among the swirling clouds and mist at the crest of the mountains. I could just make out a small yellowish patch, not more than an inch square, appearing and disappearing in the eddying mountain vapors. He told me it was a rushwork blind that hung over the entrance to Master Hakuyū’s cave.

Hitching the bottom of my robe up into my sash, I began the final ascent to Hakuyū’s dwelling. Clambering over jagged rocks, pushing through heavy vines and clinging underbrush, the snow and frost gnawed into my straw sandals, the damp clouds thrust against my robe. It was very hard going, and by the time I reached the spot where I had seen the blind, I was covered with a thick, oily sweat. I now stood at the entrance to the cave. It commanded a prospect of unsurpassed beauty, completely above the vulgar dust of the world. My heart trembling with fear, my skin prickling with gooseflesh, I leaned against some rocks for a while and counted out several hundred breaths.

After shaking off the dirt and dust and straightening my robe to make myself presentable, I bowed down, hesitantly pushed the blind aside, and peered into the cave. I could make out the figure of Master Hakuyū in the darkness. He was sitting perfectly erect, his eyes shut. A wonderful head of black hair flecked with bits of white reached down over his knees. He had a fine, youthful complexion, ruddy in hue like a Chinese date. He was seated on a soft mat made of grasses and wore a large jacket of coarsely woven cloth. The interior of the cave was small, not more than five feet square, and, except for a small desk, there was no sign of household articles or other furnishings of any kind. On top of the desk, I could see three scrolls of writing—The Doctrine of the Mean, Lao Tzu, and the Diamond Sutra. I introduced myself as politely as I could, explained the symptoms and causes of my illness in some detail, and appealed to the master for his help.

Awaken: Amazing… the way you made your way to this remote setting! And what did he say?

Hakuin: After a while, Hakuyū opened his eyes and gave me a good hard look. Then, speaking slowly and deliberately, he explained that he was only a useless, worn-out old man —“more dead than alive.” He dwelled among these mountains living on such nuts and wild mountain fruit as he could gather. He passed the nights together with the mountain deer and other wild creatures. He professed to be completely ignorant of anything else and said he was acutely embarrassed that such an important Buddhist priest had made a long trip expressly to see him.

But I persisted, begging repeatedly for his help. At last, he reached out with an easy, almost offhand gesture and grasped my hand. He proceeded to examine my five bodily organs, taking my pulses at nine vital points. His fingernails, I noticed, were almost an inch long. Furrowing his brow, he said with a voice tinged with pity, “Not much can be done. You have developed a serious illness. By pushing yourself too hard, you forgot the cardinal rule of religious training. You are suffering from meditation sickness, which is extremely difficult to cure by medical means. If you attempt to treat it by using acupuncture, moxacautery, or medicines, you will find they have no effect—not even if they were administered by a P’ien Ch’iao, Ts’ang Kung, or Hua T’o. You came to this grievous pass as a result of meditation. You will never regain your health unless you are able to master the techniques of Introspective Meditation. Just as the old saying goes, ‘When a person falls to the earth, it is from the earth that he must raise himself up.’”

Awaken: So interesting that “Introspective Meditation” apparently held the key to your recovery “meditation sickness”! Please don’t withhold the details of this esoteric approach…

Hakuin: “The Great Way” is divided into the two instruments of yin and yang. Combining, they produce human beings and all other things. A primal inborn energy circulates silently through the body, moving along channels or conduits from one to another of the five great organs. Defensive energy and nutritive blood, which circulate together, ascend and descend throughout the body, making fifty complete circulations in each twenty-four-hour period.

“The lungs, manifesting the metal principle, are a female organ located above the diaphragm. The liver, manifesting the wood principle, is a male organ located beneath the diaphragm. The heart, manifesting the fire principle, is the major yang organ; it is located in the upper body. The kidneys, manifesting the water principle, are the major yin organ; they are located in the lower body. Contained within the five internal organs are seven marvelous powers, with the spleen and kidneys having two each. “The exhaled breath” issues from the heart and the lungs; “the inhaled breath” enters through the kidneys and liver.

With each exhalation of breath, the defensive energy and nutritive blood move forward three inches in their conduits; they also advance three inches with each inhalation of breath. Every twenty-four hours, the defensive energy and nutritive blood make fifty complete circulations of the body. Fire is by nature light and unsteady and always wants to mount upward, whereas water is by nature heavy and settled and always wants to sink downward. If a person ignorant of this principle strives too hard in his meditative practices, the fire in his heart will rush violently upward, scorching his lungs and impairing their function.

Since a mother-and-child relationship obtains between the lungs, representing the metal principle, and the kidneys, representing the water principle, when the lungs are afflicted and distressed, the kidneys are also weakened and debilitated. Debilitation of the lungs and kidneys saps and enfeebles the other organs and disrupts the proper balance within the six viscera. This results in an imbalance in the function of the body’s four constituent elements (earth, water, fire, wind), some of which grow too strong and some too weak. This leads, in turn, to a great variety of ailments and disorders in each of the four elements. Medicines have no effect in treating them. Physicians can only look on with folded arms.

Awaken: So, it seems like your meditation sickness was a problem of overzealousness! But, as Master Hakuyu was saying, the way we breathe can either deplete us or replenish us!

Hakuin: Chuang Tzu said, ‘The True Person breathes from his heels. The ordinary person breathes from his throat.’ “Hsü Chun said, ‘When the vital energy is in the lower heater, the breaths are long; when the vital energy is in the upper heater, the breaths are short.’

Awaken: The power of the breath! How did you part?

Hakuin: At this point, I said to Master Hakuyū: “I am deeply grateful for your instruction. I’m going to discontinue my Zen study for a while so that I can concentrate my efforts on Introspective Meditation and cure my illness.

Awaken: What did the Master say to that?

Hakuin: A flicker of a smile crossed Master Hakuyū’s face. He replied… “It is also said that the heart becomes exhausted [of energy] when it tires and thus overheats. When the heart is exhausted, it can be replenished by making it descend below and intermingle with the kidneys. This is known as replenishing. It corresponds to the principle of After Completion mentioned before. “You, young man, developed this grave illness because the fire in your heart was allowed to rush upward against the natural flow.

Unless you succeed in bringing your heart down into your lower body, you will never regain your health, not even if you master all the secret practices the three worlds have to offer. “You probably regard me as some kind of Taoist. You probably think what I’ve been telling you has no relation to Buddhism at all. But that’s mistaken. What I’m teaching you is Zen. If, in the future, you get a glimpse of true awakening, you will smile as you recall these words of mine.”

Awaken: He didn’t want you to discontinue your practice…

Hakuin: Master Hakuyū continued: “As for the practice of contemplation, true contemplation is non-contemplation. False contemplation is contemplation that is diverse and unfocused. You contracted this grave illness by engaging in diverse contemplation. Don’t you think that now you should save yourself by means of non-contemplation? If you take the heat in your heart, the fire in your mind, and draw it down into the region of the elixir field and the soles of the feet, you will feel naturally cool and refreshed. All discrimination will cease. Not the slightest conscious thought will occur to raise the waves of emotion. This is true meditation—pure and undefiled meditation. “So don’t talk about discontinuing your study of Zen. The Buddha himself taught that we should ‘cure all kinds of illness by putting the heart down into the soles of the feet.’ The Agama sutras teach a method in which butter is used. It is unexcelled for treating debilitation of the heart.

Awaken: If I’m understanding correctly, he is saying that you were unfocused in your approach. You needed a meditation style that was more grounding and that would bring the energy downward. Is this where the “Butter Method” comes in? Could you tell me more about that?

Hakuin: Master Hakuyū explained, “When a student engaged in meditation finds that he is exhausted in body and mind because the four constituent elements of his body are in a state of disharmony, he should gird up his spirit and perform the following visualization: “Imagine that a lump of soft butter, pure in color and fragrance and the size and shape of a duck egg, is suddenly placed on the top of your head. As it begins to slowly melt, it imparts an exquisite sensation, moistening and saturating your head within and without. It continues to ooze down, moistening your shoulders, elbows, and chest; permeating lungs, diaphragm, liver, stomach, and bowels; moving down the spine through the hips, pelvis, and buttocks.

At that point, all the congestions that have accumulated within the five organs and six viscera, all the aches and pains in the abdomen and other affected parts, will follow the heart as it sinks downward into the lower body. As it does, you will distinctly hear a sound like that of water trickling from a higher to a lower place. It will move lower down through the lower body, suffusing the legs with beneficial warmth, until it reaches the soles of the feet, where it stops. The student should then repeat the contemplation. As his vital energy flows downward, it gradually fills the lower region of the body, suffusing it with penetrating warmth, making him feel as if he were sitting up to his navel in a hot bath filled with a decoction of rare and fragrant medicinal herbs that have been gathered and infused by a skilled physician.

Inasmuch as all things are created by the mind, when you engage in this contemplation, the nose will actually smell the marvelous scent of pure, soft butter; your body will feel the exquisite sensation of its melting touch. Your body and mind will be in perfect peace and harmony. You will feel better and enjoy greater health than you did as a youth of twenty or thirty. At this time, all the undesirable accumulations in your vital organs and viscera will melt away. Stomach and bowels will function perfectly. Before you know it, your skin will glow with health. If you continue to practice the contemplation with diligence, there is no illness that cannot be cured, no virtue that cannot be acquired, no level of sagehood that cannot be reached, no religious practice that cannot be mastered. Whether such results appear swiftly or slowly depends only upon how scrupulously you apply yourself.”

Awaken: And he shared a bit of his own similar experience, did he not?

Hakuin: He continued… “I was a sickly youth, in much worse shape than you are now. I experienced ten times the suffering you have endured. The doctors finally gave up on me. I explored hundreds of cures on my own, but none of them brought me any relief. I turned to the gods for help. Prayed to the deities of both heaven and earth, begging them for their subtle, imperceptible assistance. I was marvelously blessed. They extended me their support and protection. I came upon this wonderful method of soft-butter contemplation. My joy knew no bounds. I immediately set about practicing it with total and single-minded determination.

Before even a month was out, my troubles had almost totally vanished. Since that time, I’ve never been the least bit bothered by any complaint, physical or mental. “I became like an ignoramus, mindless and utterly free of care. I was oblivious to the passage of time. I never knew what day or month it was, even whether it was a leap year or not. I gradually lost interest in the things the world holds dear, soon forgot completely about the hopes and desires and customs of ordinary men and women. In my middle years, I was compelled by circumstance to leave Kyoto and take refuge in the mountains of Wakasa Province.

I lived there nearly thirty years, unknown to my fellow men. Looking back on that period of my life, it seems as fleeting and unreal as the dream-life that flashed through Lusheng’s slumbering brain. Now I live here in this solitary spot in the hills of Shirakawa, far from all human habitation. I have a layer or two of clothing to wrap around my withered old carcass. But even in midwinter, on nights when the cold bites through the thin cotton, I don’t freeze. Even during the months when there are no mountain fruits or nuts for me to gather, and I have no grain to eat, I don’t starve. It is all thanks to this contemplation.”

Awaken: What were his parting words?

Hakuin: “Young man, you have just learned a secret that you could not use up in a whole lifetime. What more could I teach you?”

Awaken: A true renunciate… he gave up the concerns of the material world and dedicated himself to his practice. If you could sum up this advice about focused practice and grounding the vital energies, what would you say?

Hakuin: Long ago, Wu Ch’i-ch’u told Master Shih-t’ai: “In order to refine the elixir, it is necessary to gather the vital energy. To gather the vital energy, it is necessary to focus the mind. When the mind focuses in the ocean of vital energy or field of elixir located an inch below the navel, the vital energy gathers there. When the vital energy gathers in the elixir field, the elixir is produced. When the elixir is produced, the physical frame is strong and firm. When the physical frame is strong and firm, the spirit is full and replete. When the spirit is full and replete, long life is assured.”

Awaken. Thank you. And I thank you wholeheartedly for sharing your time, your story and your wisdom with our readers today. You have been one of my true inspirations for so many years!

This is Awaken’s Dream Interview, conducted by Donna Quesada, and All Answers are Verbatim from Zen Master Hakuin who lived between 1689 and 1769.