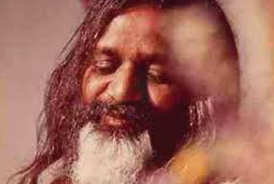

by Deepak Chopra: I last sat with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi more than 10 years ago. He left an indelible impression, as he did on everyone.

His extraordinary qualities are known to the world. Without him, it’s fair to say, the West would not have learned to meditate.

His extraordinary qualities are known to the world. Without him, it’s fair to say, the West would not have learned to meditate.

During the Cold War era a reporter once challenged him by saying, “If anything is possible, as you claim, can you go to the Soviet Union tomorrow with your message?” Without hesitation, Maharishi calmly replied, “I could if I wanted to”. Eventually he did want to, and meditation arrived in Moscow several years before the Berlin Wall fell.

In his belief that world peace depended entirely on rising consciousness, Maharishi was unshakable. The Bhagavad Gita declares that there are no outward signs of enlightenment.

The point is underscored in many Indian fables and scriptures, which often take the form of a high-caste worthy snubbing an untouchable, only to find that the untouchable was actually a god in disguise. For his part, Maharishi had three guises, and perhaps in the end they were also disguises. He was an Indian, a guru and a personality.

His personality was highly quixotic. Over the 50 years of his public life, Maharishi never lost his charm and lovability. He had these qualities to such an extent that westerners took him to be a perfect example of how enlightenment looks – kind, sociable, all-accepting, and light-hearted – when that is far from the case.

His presence was more mysterious than good humour can account for: you could feel it before entering a room. But if you were around him long enough, the older Maharishi in particular could be nettlesome and self-centred; he could get angry and dismissive. He was quick to assert his authority and yet could turn disarmingly child-like in the blink of an eye.

The Maharishi, who was an Indian, felt most comfortable around other Indians with whom he chatted about familiar things in Hindi. He adhered to the vows of poverty and celibacy that belonged to his order of monks, despite the fact that he lived in luxury and amassed considerable wealth for the TM movement.

What gets overlooked is that he viewed wealth as a means to raise the prestige of India in the materialistic West. Maharishi was deeply concerned that he might be the last embodiment of a sacred tradition that was quickly being overwhelmed by modernisation. These two Maharishis are the only ones that the outside world knew.

If you came under the power of his consciousness, however, Maharishi the guru completely overshadowed every other aspect. Nothing could be farther from the truth in Maharishi’s case.

He was venerated by the venerable and considered holy by the holy. His capacity to explain Vedanta was unrivalled, and if he accomplished nothing else in his long life, his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita insures his lasting name.

I was commissioned around 1990 to write a book about him. But even after spending hundreds of days in his presence, one could not capture him, either on paper or in one’s mind.

The enlightened person ceases to be a person and attains a connection to pure consciousness that erases all boundaries. My deepest gratitude goes to Maharishi for showing me that this state of unity exists outside folk tales, temples, organised religion and scripture.