by Carolyn Gregoire: In some Buddhist traditions, there’s a prayer in which one makes a rather unusual request of the universe: Bring me challenges and obstacles.

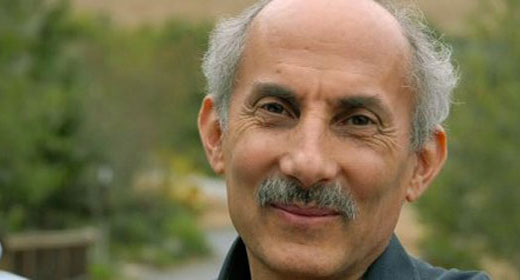

“In certain temples that I’ve been to, there’s actually a prayer that you make asking for difficulties,” Western Buddhist master Jack Kornfield told the Huffington Post. “May I be given the appropriate difficulties so that my heart can truly open with compassion. Imagine asking for that.”

Being grateful for not only life’s blessing but also its suffering is a key component of living a spiritual life — and more broadly, to a fulfilling and meaningful life — according to Kornfield,.

Trained in the monasteries of India, Thailand and Burma, Kornfield has studied and taught meditation for over 40 years, and has pioneered transmitting ancient Buddhist spiritual teachings to a modern Western audience. After working in the Peace Corps and earning a doctorate in clinical psychology, Kornfield founded the Insight Meditation Center in Barre, MA, and later, Spirit Rock Meditation center in Marin County, California. He’s also authored a number of books on mindfulness, compassion and Buddhist psychology, notably his 1993 bestseller A Path With Heart.

So what’s one of Kornfield’s secrets to abundant gratitude? Don’t take life so seriously, or get so wrapped up in your own everyday dramas that you forgot to see the beauty that is constantly surrounding you.

“This life is a test — it is only a test,” Kornfield wrote in A Path With Heart. “If it had been an actual life, you would have received further instructions on where to go and what to do. Remember, this life is only a test.”

HuffPost Health Living spoke to Kornfield about the importance of being grateful (even for the bad things), the “mindful revolution,” and the importance of giving back.

Why is gratitude an essential component of a spiritual life?

If we see the world as sacred, which is an expression of the spiritual life, then gratitude follows immediately and naturally. We’ve been given the extraordinary privilege of incarnating as human beings — and of course the human incarnation entails the 10,000 joys and 10,000 sorrows, as it says in the Tao Te Ching — but with it we have the privilege of the lavender color at sunset, the taste of a tangerine in our mouth, and the almost unbearable beauty of life around us, along with its troubles. It keeps recreating itself. We can either be lost in a smaller state of consciousness — what in Buddhist psychology is called the “body of fear,” which brings suffering to us and to others — or we can bring the quality of love and appreciation, which I would call gratitude, to life. With it comes a kind of trust. The poet Pablo Neruda writes, “You can pick all the flowers, but you can’t stop the spring.” Life keeps recreating itself and presenting us with miracles every day.

It’s easier for us to feel grateful for things that make us happy and that make life easy for us. But how do we learn to be grateful for life’s “10,000 sorrows”?

I remember my meditation master in the jungles of Thailand who would ask at times,Where have you learned more compassion? Where have you learned more? Where has your heart grown wiser — in just having good times, or going through difficulties? There’s a Buddhist-oriented therapy in Japan called Naikan Therapy, and one part of that training is to review your life and begin to remember all the things you have gratitude towards, even the things that were difficult and taught you lessons. Or even the people that were difficult, sometimes in your own family — [remembering] the gratitude you have for family, that they’re even there.

And speaking of gratitude, in a group that I taught recently, there was a man who spoke up whose son and daughter-in-law had become meth addicts. They were both addicts to the point where this fellow and his wife as grandparents had to take the children and raise their grandchildren. After a moment of great despair, he began to do a gratitude practice to see what he could be grateful for. He was grateful to have the grandchildren in that way, he was grateful that his children were still alive and that they were considering treatment. He was grateful for the depths of compassion that had grown when he learned about the waves of addiction that were prevalent in the country, and that he could somehow contribute to bringing an end to it…. He said that by being able to find gratitude as well, he was able to bear the difficulties and to bring some grace and love to it.

What is the connection between gratitude and mindfulness? Is it that when we’re more mindful, it’s easier for us to experience gratitude because we’re more aware of the good things?

To become mindful — which Zen master Suzuki Roshi also called “beginner’s mind” — is to see the world afresh without being lost in our reactions and judgments, and in seeing it afresh with a clarity, we begin to be able to respond to the world rather than react to it. (I like to translate mindfulness as loving awareness — an awareness that knows what’s present, and also brings a quality of compassion and lovingkindness to that.)

The cultivation of mindfulness — which modern neuroscience has now shown in 3,000 papers and studies in the last two decades to help bring emotional regulation, steady attention and physical healing — really allows us to become present for our own body, for the person in front of us, for the life we’ve been given. Out of that grows quite naturally the spirit of gratitude. Now it turns out, like all good things, they feed one another. Cultivating an opening to gratitude also helps us to become more mindful of the life around us and what circumstance we’re in.

We live a culture defined by consumerism, materialism and addictions — so often we feel we’re not enough, and we’re constantly trying to fill a void with more “stuff.” Why is American society in particular so in need of gratitude, and how can we cultivate this sense of appreciation and abundance when we’re socialized to live with a sense of lack?

One very articulate writer on this subject, Anne Wilson Schaef [author of When Society Becomes An Addict], has described ours as an addicted society. Whether it’s consumerism or addictive substances or just keeping ourselves busy or being online or working 80 hours a week, we have things that keep us busy because, in some ways, the culture wants us to keep engaged and not to look around much… not to see the struggles of people, the continuing injustice, the economic disparities, the people who are hungry, climate change. What becomes clear is that there’s no outer fix or satisfaction — no amount of computers, no amount of nanotechnology or biotechnology and all the great things that we’ve developed that will stop us from continuing warfare, racism and environment destruction.

Those outer developments have to be matched by a transformation of human consciousness to realize that we are interdependent and we depend on the air we breathe, and on people in other nations as they depend on us. We are woven, as Dr. Martin Luther King said, into a single garment of destiny. When we see this, we begin to realize that the values of consumerism and getting more and more — which start to become emptier and emptier — don’t satisfy the heart. When we look at what’s satisfied us in the past week or month or decade, it’s been the connections, the love and the openness of our lives to the places we’ve traveled and the people we’ve met. This really is the basis for gratitude. Then we start to sense that it is possible to live with a quieter mind and an open heart, and with a sense of satisfaction within ourselves — it’s the satisfaction of well-being.

We are beginning to witness the seeds of this shift taking place, with the recent explosion of interest in meditation. (This year, for example, TIME declared a “Mindful Revolution” underway in American culture). You’ve been a key player in bringing Buddhist practices to the West for more than 40 years now. How have you seen attitudes towards mindfulness shift in that time?

Mindfulness, in the beginning, was associated mistakenly with a religious practice, when in fact Buddhist teachings, at their essence, are a science of mind which simply offer us these universal trainings that can steady and balance our attention, and give us a deeper connection to ourselves and one another. Fortunately, with all those 3,000 research studies that I mentioned and the great neuroscience that’s been done, it becomes clear with the understanding of neuroplasticity that we can train our mind and our heart through attention. It helps schoolchildren, it helps in healing and clinics, and it helps attention, whether you’re writing computer program or a business plan or making love or creating a piece of art — the ability to steady the attention to be fully present is an enormous gift. I’ve seen mindfulness as a training and as an opportunity for the growth of presence and wisdom to be spreading in all these areas. I’m really happy for the benefit that it’s bringing.

Some critics of mindfulness have argued that the practice is too focused on the individual, at the expense of fostering a spirit of collectivity and positive social change. Do you think this is true? How do giving back and service figure into a spiritual practice?

It’s very simple. There’s a saying, “There are only two things to do: Sit, and sweep the garden.” This is like breathing in and breathing out. You quiet the mind and the heart so that you’re connected to yourself and listen to what really matters. Then you get up from that stillness, and if people are hungry, you offer food. If there’s injustice, you offer yourself for the healing of that injustice.

In fact, it allows us to become agents of change because we are actually attentive and present for what is without being overwhelmed by it and without distracting ourselves. In that way, mindfulness is actually one of the necessary components of making a real transformation in whatever field or dimension of society we would choose. It supports it, and it leads towards it, and it allows people to do it without burnout. If you work for good causes but you do it out of anger and frustration and guilt — and all of those other motivations I’ve seen among activists I’ve worked with — you will burn out. But if that same compassion and care comes instead from the power of love and steadiness and a deep devotion to what is just and right, it has equal if not greater power.

Mahatma Gandhi took one day a week in silence, even in the midst of marches of thousands and the ending of the British coloinal empire. When everything was in the middle of this huge transformation, he would say, “I’m sorry, this is my day of silence.” And he would sit and quiet himself and try to listen to what was the most compassionate and skillful and powerful response he could make, coming from that deep center of wisdom. So rather than removing us from the world, it allows us to affect the world in a different and in many cases more profound way.