by Stephen Lankton, MSW, DAHB: I am writing about Erickson‘s contribution to therapy in terms of epistemology and ontology and run the risk of being mistaken as an article on philosophy.

As a family therapist and hypnotherapist, I am not qualified nor prepared to do justice to the field of philosophy – either traditional or post-modern. But I do feel comfortable speaking about epistemology (I will use the single term to refer to both the epistemology and ontology ala Bateson, 1972) which is used here to refer to the general approach taken and presuppositions made about people and problems.

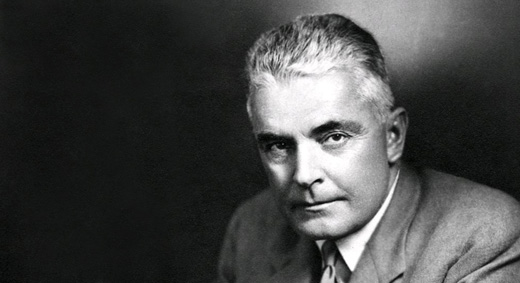

Years ago, I heard Dr. Dan Goleman, editor of Psychology Today magazine state that Dr. Erickson had made a contribution to psychology parallel to Freud‘s. Where Freud had made his contribution in terms of theory, Erickson had made an equal impact in terms of intervention. Indeed, many professionals feel that Erickson’s significant contribution was the advancement of the use of hypnosis, others feel it was his uses of language in one way or another: indirect suggestion, metaphor, anecdotes, confusion, therapeutic binds, etc. Others would argue that his contribution was the development of concepts known as utilization, indirection, speaking the client’s language, and so on.

I suppose that arguing the merits of one of these aspects of intervention over another is a matter of personal and professional judgment. But I would like to express what I believe to be a central underpinning of all of these interventions – his approach to people and problems – or if you like, his epistemological and ontological position.

Before I begin writing about this I should perhaps warn or remind you that thought and experience are not linear even though writing is. The act of communicating thoughts can also be non-linear with the exception, that is, of the written and spoken verbal portion. Writing and communicating, as I am, about thought and communication is likely to result in some difficulty. The difficulty we will encounter will amount to some sort of paradox and possible misunderstanding by my use of comparison and contrast. While what I wish to express is very complex, I may be able to reduce confusion by using relatively direct and simple words whose translation into other languages will minimize misunderstanding.

Finally, to make the matter of bringing home my point a bit harder, I have chosen a topic that concerns the thoughts and perceptions of Dr. Erickson. Since he is neither present to defend himself from what I am about to say, nor do his written works directly deal with the issues I am presenting, it might be concluded that I am about to speak about something I don’t know anything about and can not communicate even if I do! Well, with such a task before me, I better get right to it.

Background

I would like to begin with some ancient history, as I feel this will put the current ideas in a powerful relief. I want to elucidate the concepts which can be seen in the following chart. The left column of the chart refers to a development in Western thought spanning centuries and ending within the last few decades. While such an overview will over-simplify the life-works of many famous persons, it will suffice to make one point clear regarding the birth of psychology and the epistemology from which it is being weaned.

From ancient days we have been given to believe that an independent Truth exists. To illustrate this perhaps I should begin with 4th century b.c. Plato for convenience. His contribution of “a priori deductive idealism” informed us that there exists an a priori Truth of the universe which in some manner must come to be known by us. On the Heavens in 340 b.c. was written by his student Aristotle and introduced us to “induction” and empirical observation, but more importantly perhaps, Aristotle is known for the early syllogisms of logic by means of which a person with very little sensory investigation might reason his or her way to the Truth. For example, for spiritual reasons he argued that Earth was the center of the Universe. Within just 140 years, an elaboration of this was accomplished by Ptolemy and known as the Ptolemic model of the Universe it became widely accepted. It is astounding that this idea built upon the premise of a knowable Truth went unquestioned for almost 2000 years – because it “cuts deeply” into the souls of our most mundane routines even today. Just as it blinded those who looked into the skies it still blinds many of us as we look into the lives of our clients and patients.

Comparison Chart

| Truth exists and can be “known” | Co-creation of what is considered true |

| Observing carefully will reveal the truth | Participation is all that is possible – observation is participation |

| Adversarial position is taken by nature | Cooperative position is taken by nature |

| Observers are separate from the observed | Observers are in the system they observe |

| Reduction of larger parts will get closer to the truth | Punctuation of experience is basically arbitrary |

| Labeling of parts is a banal event | Pattern identification is limited by the labeler’s experience and choices |

| Problem-oriented – identify causes | Goal-Oriented – solves the task |

| Pathology-“uncovering” – disease can be uncovered | Health-discovering helps build desired resources |

| Past-oriented – causes lie in past | Future-oriented – purpose lies in present and immediate future |

| Individuals operate independent of environment | Individuals and environments form an ecosystem |

| Causes are inside of the individual | Problems are reciprocally and cyclically between and with parts of the system |

| Experts”give” treatment | Change agents help create a context for problem solving |

Traditional epistemology is also based on a separateness from nature and an adversarial posture toward nature. We might trace this too to Plato but the principle of mind-body dualism, found in Plato was greatly magnified by the Latin church father Saint Augustine, 354-430 when he wrote with authority the City of God. Already blinded in their world view, people had come to seek the truth by rising above the adversarial human body which seemed to tether them to the lesser world of the senses. In this atmosphere it is easy to understand how an entire race could delude their senses for 14 centuries until the Copernican revolution was triggered. We developed centuries of presuppositions that we were separate from nature and able to seek an independent Truth.

This began when the Pole, Nicholas Copernicus, circulated his model of the Universe anonymously in 1514 a.d. It was nearly 100 years before the heretical idea, that Earth was not the center of the Universe, could take root in 1609. And this came only after the invention of the telescope – when Galileo using the Kepler telescope discovered the moons in orbit around Jupiter. This was, at last evidence that all of the heavens did not obit the Earth. Finally people began to have the evidence and the courage to reason from our more careful observations. In a way, as I will explain, this stroke of brilliance known as the Enlightenment proved to be a mixed blessing for psychology. This was due primarily to the slightly misguided notion that we could observe linear-causality in the universe without effecting it – but I’m getting ahead of my story. I want to build the drama and impact of the growing traditional epistemology so I can better emphasize the climate in which we now reach for an alternative.

The age of reason was born and with it enormous scientific and intellectual advancement of the 17th century. But it further alienated us from a sense of cooperation and participation in nature. For instance, in 1620, the empiricist, Francis Bacon wrote Novum Organum and put forth the idea that we must torture nature and make her give up her secrets. This, by the way, was the same year that the first ships carrying slaves landed on our colonial shores. Why am I telling you all of this in a paper on psychotherapy? Because we should look at the deep impact which gave rise to psychology: In this age of Enlightenment the Truth exists in nature independent of the observer, who is separate from and at times extremely adversarial toward it, even torturing it. We came to expect it as fact that we were impartial observers and if nature or even some race of people did not seem to conform to our conception, we could torture them and make them give up their secrets. This has far reaching ramifications for our culture and one of which is that it is easy to see how we could come to label people as resistive, pathological, and treat them with suspicion even in this post-modern age of therapy.

Referring to my chart we see that I have now illustrated what I mean by saying the traditional epistemology embodies the concepts of “truth,” “observing,” “separate,” and “adversarial.” The next two items are “reduction” and “labeling.” I see these as part of the traditional epistemology rising from the incredible ideas that emerged within the next 150 years. Just to illustrate briefly, Ole Roemer in 1676 determined the speed of light fairly closely for his time. This sort of knowledge was an advancement of incredible dimension! It must have seemed that there was nothing we could not reduce, label and measure! I’m sure that none of us in this room could come anywhere close to such a feat today with all of our desktop computing power – and what a reinforcement for a reliance upon the traditional epistemology that was developing. To add further reinforcement, Descartes’ student Newton, in 1687, developed the laws of motion, calculus and the principle of gravity, space and time.

I am so enthusiastic about how these accomplishments were achieved by these individuals that I am always tempted to deviate from my central point and illustrate in detail. But I will keep on the point, that this world-view was incredibly seductive and it was quickly developing a forceful momentum as all sorts of learning and knowledge was advanced. To illustrate, I’ll add the following few: Within less than 200 years Clerk Maxwell had developed the wave theory. Twenty years later Michelson and Morley performed their famous experiments with light that was later re-examined by Einstein. My point is that the changes brought by observation and reductionism were so incredibly remarkable that they gave the world enormously moving details about the nature of things. At this point the tools of mathematics and observations had taken us from the heavens all the way to the inside of the atom and all the while taught us to reduce and label, to observe and feel separate from, and to seek the truth as if we did not influence that which we sought. This movement told us that we could observe the Truth in nature and it must be that this methodology, this epistemology was correct and should be followed. And, most importantly for my thesis today, is that this was 1887, just 9 years before Freud’s work on hysteria. In 1986 Sigmund Freud entered the scene and launched the ship of psychology. Naturally, he would be hugely influenced by the science of his day and the belief in natural law and universal order. And it was in these waters his ship was to sail. Naturally, he could be expected to invent an approach that searched for problems with linear causes, rooted in the past. By reduction he would look inside the individual and consider himself capable of finding a truth by observation. The scientist and the psychiatrist was an expert who would gather the facts and provide the passive patient with a treatment leading to a “cure” just as a physician would provide surgery or medication. Of course, therapists would reduce and label reified parts of individuals as they looked for the cunningly hidden causes within. When the subject did not respond to the expert he or she was “resistant” or worse.

Let’s sort of flip the channel for a moment. Contrary to this growing force there was a rising problem in the epistemology. Hume and later Kant in 1871 had mentioned aspects of it. In the natural sciences several experiments were leading thinkers to the conclusion that we imposed order on the universe by our attempts to merely observe it. One could see this in the “wave-particle” theory (11 years before Kant), in the Michelson/Morley problem with light, in the conceptualization of the quantum principle in 1920 by Max Plank, and, of course, in the “Indeterminacy Principle” of Heisenberg in 1926 – better known as the “uncertainty principle.” But in light of the scientific achievements, I suppose, none of this made much sense at the time. In fact Freud had actually aggressively dismissed Kant’s ideas (Freud, 1966, p. 538). Yet, particle physics and quantum math arose help theorists to come to grips with the anomalies of this epistemology (Hawking, 1988) and begin to understand a participatory universe. These understandings were vague to those outside of the advanced science labs and so, psychology continued to travel in the direction it was launched. Unfortunately, it is still doing so today in many ways and, of course, that is why I am emphasizing Erickson’s contribution to illustrate this emerging epistemology.

So, let’s turn our attention to more recent times. As physics and mathematics changed to develop a different epistemology the same began to happen in social science. Perhaps the most articulate and capable of the thinkers grappling with this was Gregory Bateson. After his work on self-governing mechanisms and cybernetics he turned to the human systems and created a study team known as the “communication project.”

In 1952, Bateson’s research project on communication elected to investigate Erickson’s work since he, more than any other therapist known to the team, was concerned with how people change (Haley, 1985a) and not how they were sick. Erickson’s pragmatic contributions were appreciated by the aesthetically oriented Bateson (Keeney, 1983) and the members of the research project John Weakland, Jay Haley, Don Jackson, and William Fry. The group recognized this in the important 1956 paper, “Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia” (Jackson, 1968a) wherein Bateson, Jackson, Haley and Weakland discussed examples of Erickson’s work. Subsequently, members of the clinically oriented Mental Research Institute continued to cite Erickson for several years (Bateson, 1972; Haley, 1963, 1967; Jackson, 1968a, 1968b; Satir, 1964) as they developed family therapy. Under the later direction of Watzlawick, Weakland, and Fisch, MRI continued to provide robust models for ideas and techniques of Erickson’s work throughout the 1970s, especially as they related to change in human systems and brief strategic therapy. Much of Erickson’s work was simultaneously attended to by hypnotherapists, as he was the founder, in 1957, of the American of Society of Clinical Hypnosis and editor for ten years of its Journal.

As the Bateson team attempted to articulate a transactional approach to therapy, Haley published a remarkable work elucidating many examples of Erickson’s “strategic therapy” work with both individuals and couples (1963). It seems clear in retrospect that Erickson’s work contained some of the sparks of inspiration regarding an emerging approach and an emerging language in therapy.

Bateson frequently attempted to clarify the difference between the traditional approach and emerging approach with ideas such as: “The difference between the Newtonian world and the world of communication is simply this: that the Newtonian world ascribes reality to objects and achieves its simplicity by excluding the context…In contrast, the theorist of communication insists upon examining the metarelationships while achieving its simplicity by excluding all objects (Bateson, 1972, p. 250).” He saw that with little exception, the entire profession of therapy had been influenced with the belief, common to psychoanalysis, that we could know the truth of a separate reality and that acts of observation did not alter this external reality. Psychology’s posture toward reality was separation from it – studying it by reduction. The simple act of reducing and labeling seems innocent enough on the one hand but does not credit the “observer” with the action of inventing the label which is applied, then punctuating the stream of experience and ordering the events. Consequently, Bateson felt that traditional therapy, in its attempts to search for problems rooted in the past, developed a rich language to describe the intrapsychic domain of single individuals. This description often pathologizes the individual and typically excludes or diminishes his or her present life context.

The therapeutic stance of “separateness,” pathology orientation, and search for problems occasionally result in an adversarial position being taken. The developed language of therapy reflects this adversarial position with metaphors of resistance, conflict, defense, hidden motive, suppression, power, and so on. Szasz (1961) and Laing (1967, 1972) have spoken eloquently about the individual and social injuries which are the by-product of attempting to help within such a framework. Placed in an adversarial position, purposefully or inadvertently, labeled individuals will easily demonstrate more behavior which will reinforce a therapist’s conviction about the independent existence of an internal pathology. It was this very trend that Erickson wished to avoid throughout his career (Erickson, 1985) and which seemed to attract Bateson and his team.

In an attempt to clarify the unique differences between the traditional and emerging views I listed the features of this Ericksonian approach in the right hand column of the chart. I hope my language is more palatable than Bateson’s and yet respectful to his conception of the distinctions. Instead of believing in an observable truth, might we better say that we co-create the truth with our participating. I can’t think a a more obvious way to understand Erickson‘s use of reframing and retrieving experiential potentials. To summarize a well known case: When the newlyweds came for counsel due to the lack of sexual intercourse, it was not that the husband did not have love for his bride (which might have seemed true to the observer) and it was not formulated that the man had erotic desires for his mother but experienced internal conflicts due to his fear of retribution from his father. Rather, Erickson offered the view that he was attempting to express his unique and profound desire for her in a way he had not previously been able to do and he needed to develop some special manner to make his superlative expression now. In this simple case we see Erickson’s contribution clearly: his way of viewing the situation as not that of an expert viewing the truth linked to the past in a causal and linear manner, but that of an active participant, helping create a context for change, discovering health as it unfolds, and orienting them toward the current and future goal by retrieving resources.

Indications Of The New Epistemology

I want to briefly discuss 4 aspects of therapy as they can reflect the difference between the traditional and emergent epistemologies. I will then demonstrate Erickson’s position regarding these issues. The four issues I will consider here are the purpose and use of suggestion, metaphor as indirect intervention, the meaning of a symptom, and what constitutes a cure.

Some of the distinctive features of therapy and interventions associated with Erickson’s work are important, not for their “uncommon-ness” but for their function as a vehicle to bind the therapist and client in the process of co-creating a context for change. We might look at indirection and its use as one example. The traditional epistemology favors the use of direct suggestion. Direct suggestion could be used by the expert to tell the observed subject just what he or she should do to improve from the problem he or she brings to the office. Indirect suggestion, on the other hand, is presented so that a client will apprehend that portion which is of subjective value and apply it to the process of retrieving and associating experiences needed to reach the current goals. Indirect suggestion assumes an active and participating client with a certain innate wisdom. The therapist learns from the response of the client when to elaborate the presented ambiguity in even more helpful ways.

The Uses of Suggestion

| Use of suggestion | direct, authoritarian | indirect, permissive |

| Indirection, metaphor | if done by client it is an indication of primary process, a sign of client regression | resource retrieval, allowing client to create a unique response, an experiential context which helps build a bridge for learning |

| Meaning of symptom | internal conflict, not well defended | a communication about developmental needs |

| Cure | due to insight, ego strengthening, internal conflict resolution | development of new relational pattern and creative response to environment |

It is easy to see that the conception of a problem or symptom as a sign or a communication is another facet of the emerging epistemology. The existence of and continuance of the symptom is many things: it is feedback the client can not associate to the needed resources, it is a probe by the client to stimulate the environment, it is a communication and so on. These views are part of the interaction, goal-oriented, future-oriented view. Contrast this to the view that a symptom is a sign of an internal conflict within an individual. People are indeed conflicted when they are not solving problems in an adaptive and creative manner. The decisive feature between the old and new epistemologies may lie in the conception of priority as it pertains to the idea of a symptom. Is this strip of experiences we call a symptom due to the conflict within or is the symptom a sign of the person’s attempts to solve a relational problem? It seems reasonable to me to suggest that if we say a symptom is the former, we are of the old tradition, if we say the latter is more accurate, we operate from the emergent view.

The final area of “cure” can also be seen to reflect the differences in approach. The traditional view of cure, as I have understood it in my education, is related to the resolution of an internal conflict, building of ego strength in the individual, the removal of resistance, removal of symptoms, and finally the capacity for work and love. The emphasis in this scenario is on an individual in a vacuum who has somehow “worked through” events from the past about which he or she was conflicted, lacked ego strength, and from which he or she developed parataxic distortions. Of course this often involved insight and sometimes involved corrective emotional experiences. This is a concept of cure based upon a past-orientation. From a future-oriented perspective a cure would be evaluated on the basis of the loss of the symptom, development of adaptive relationships with those persons in the current social environment, and the acquisition of new skills for handling developmental demands. Let’s now look at how Erickson’s contribution is expressed in these different areas as a means to evaluate his reliance upon the emerging epistemology.

Erickson’s Changing Views

I suspect that many students of Erickson’s work have encountered the difficulty of sorting out the “real” Erickson. Some may have read articles which claimed that Erickson was very directive and not indirect as others have claimed. Some contend that he was very authoritarian and others claim he was permissive. One can either check the sources of these comments and sift through them for signs of professional jealousies and alliance, first hand accounts versus second hand knowledge, or perhaps just decide not to over-generalize and conclude that Erickson displayed a wide range of conduct which subsumed both positions. But, like most of us, Erickson’s views changed and developed over time. Seeing his work in 1945 one would take a different awareness than one would viewing his work in 1975. In order to demonstrate how his view of clients and problems reflected this emerging epistemology I want to chronicle this change in those 4 previously mentioned areas which have bearing on the discussion. Those areas are; purpose and use of suggestion, use of metaphor as indirection, meaning of symptom, and what is a cure.

Direct suggestions and redundant suggestions

We see in Erickson’s early explanations of hypnosis a sign that he moved from the position of an authoritarian expert who “did” something to a client, to a position of co-creator of a context for change where he “offered stimuli” to the subject who as to put ideas together for him or herself. In a 1945 published transcript we find him using the redundant repetition of “sleep” in the following sentence: “Now I want you to go deeper and deeper asleep.” (p. 54) and the statement “I can put you in any level of trance” (p. 64) [italics mine] (Erickson, M. With Haley, J. & Weakland, J. 1967)

Interesting, by 1976 we find Erickson making a full reverse on this method of redundant suggestion and writing that he believed indirect suggestion to be a “significant factor” in his work (Erickson, M. H., Rossi, E. L., & Rossi, S. I, 1976, p. 452). But more interestingly still, is the growth we see by the end of his life published after his death in 1980. Here he has come to take the position, not of authoritative expert who makes someone go into trance, but of someone who will “offer” ideas and suggestions (p. 1-2). Contrary to his early conduct he stated, “I don’t like this matter of telling a patient I want you to get tired and sleepy” (p. 4) [italics mine] (Erickson, M., Rossi, E., 1981). This is the exact opposite position and represents a straight departure from the traditional to the emerging epistemology!

Metaphor as indirect intervention

There can be little doubt that Dr. Erickson was comfortable with the role of ambiguity in therapy. In 1944 Erickson used a complex story to help stimulate a client’s neurotic mechanisms (Erickson, 1967). So, we see from very early work that he, nevertheless, felt that therapy was a matter of offering ambiguity for the client to develop his or her own unique response. Still in 1954 Erickson was delivering what he called “fabricated case histories” to help a client be relieved of fleeting symptomatology (Erickson, M., 1980, p. 152). And, of course, by the year 1973 we see several examples of case stories used for illustrating points in therapy and normal communication (Haley, J., 1973). Finally, in a 1979 publication, we actually see section headings on “metaphor” as intervention (Erickson, M., Rossi, E., 1979). It would be most correct to conclude from this evidence that Erickson’s use of ambiguity, permissiveness, and indirection in therapy was present from the beginning of his work and progressed with increasing frequency.

The meaning of symptoms

Regarding the meaning that Dr. Erickson attributed to symptoms we find a pattern of change from the traditional, analytic view in his early career to that of the systemic and interpersonal view by his death. You might recall that his medical degree was obtained in 1928 and he then went to Colorado General Hospital for his internship and was there until 1938 or 39. But as late as 1954, he wrote “The development of neurotic symptoms constitutes behavior of a defensive, protective character” (Erickson, M., 1980, p. 149). This strikes me as a traditional analytic view with concepts like “defense and attack.”

But, again we see movement to the emergent epistemology by 1966, when he wrote “Mental disease is the breaking down of communication between people” (Erickson, M., 1980, p.75). And, finally, in 1979 he had arrived at the fully formed idea state in “Symptoms are forms of communication” and “cues of developmental problems that are in the process of becoming conscious” (Erickson, M., Rossi, E., 1979, p. 143). This view is much more in keeping with the ideas expressed verbally by Erickson on repeated occasion, that he did not have a theory of personality and invented a new theory with each unique client.

Cure seen as reassociation of experience not direct suggestion

One of the most revealing comparisons we could do is to look at what Erickson thought of the idea of cure. Here we see that there was essentially no change between his view from 1948 to the end of his work. In 1948 he recognized that cure was not the result of suggestion but rather, developed from reassociation of experience (Erickson, M. , 1980, vol. 4, p. 38). (In this citation we also can see that Erickson did not wish to use direct suggestion in treatment but preferred to use indirect suggestion for treatment and, in the earlier 1954 quote, he still used direct suggestion for induction.) We see essentially the same quote in Erickson’s writing at the end of his career (Erickson, 1979; Erickson, M. & Rossi, E., 1980, p. 464; and Erickson, M. & Rossi, E., 1981).

The point which we might draw from this, is that, while his use of suggestion and redundancy changed over the course of his career from the traditional to more permissive, his use of permissive ambiguity, what constituted a symptom, and what facilitated a cure was consistent from his earliest records until his latest works. We also see that reliance upon this emergent epistemology increased in frequency over time. Clearly, in these important and revealing ways, Erickson’s work evolved from a modification of the traditional approach to a full representation of the emergent epistemology. And, this happened increasingly from the period covered from 1944 until the end of his career.

The Epistemology Of Use

Are we thinking about therapy to analyze it or to use it? Perhaps the answer to this should determine our guiding principle. Restricted as we are by an inability to speak a language of phenomenology, discourse regarding the on-going process of therapy easily digresses into an explanation formed from traditional epistemology. The solution to this dilemma is the development and acceptance of a more adequate language…but then, as I began, I recall that speech is linear. Perhaps living in a participatory epistemology and speaking in a linear and causal epistemology is the horse we must ride. And, too, perhaps the tension between our ability to conceptualize and participate in creating our own future and that of our clients in therapy must continue. Indeed, I rather wonder if that tension is not like a motivating force in the evolution of mind. And, in the end, we must only be partially satisfied with writing about the change process and not let this limitation distract us from attempts to research and refine the participatory process of the emerging epistemology which we actually find ourselves working toward in therapy. But I do not believe Erickson’s greatest contribution was his remarkable interventions. In fact, his interventions can be used by therapists bound in the traditional epistemology and they will “work” so to speak – but they will be no more useful, exciting, or dramatic than the conventional interventions on most occasions. Furthermore, it will be a chore to conceive of them from that framework. However, they seem to almost flow from the posture created with the emerging epistemology and create a total package for powerful change even, at times, in a brief number of sessions. I have to conclude then, that interventions are not the greatest contribution made by Erickson’s life-work but rather it is his epistemology and from that the interventions Dan Goleman spoke of are secondary and almost unimportant.