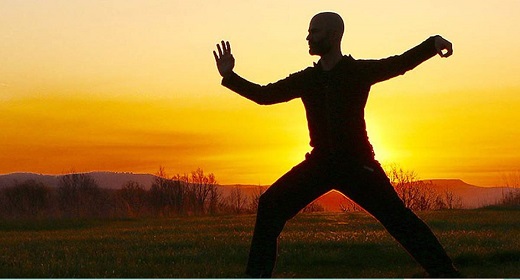

by Claudia Cummins: In 1985, Adrian Piper stopped having sex. A longtime yoga practitioner, Piper committed herself to the practice of brahmacharya (celibacy), which is touted as an important step along the pathway to enlightenment…

Still resolutely committed 17 years later, Piper calls this practice the greatest spiritual gift she’s ever been given.

“Brahmacharya has changed my perception of myself, of others, of everything,” she says. “It’s been so interesting to realize how much of my ego-self was bound up with sexuality and sexual desire. And the effect on my sadhana [spiritual practice] has been most profound. I’m not sure I can put it into words. Let’s just say there’s definitely a good reason why all spiritual traditions recommend celibacy. Sex is great, but no sexual experience-and I’ve had a lot of them-could even come close to this.”

Piper is not alone in praising the transformational gifts of brahmacharya. Celibacy plays an important role in the yoga tradition-indeed, some would say, a critical one. The father of classical yoga, Patanjali, made brahmacharya one of the five yamas, or ethical precepts in the Yoga Sutra[Chapter 11, verse 30] that all aspirants should adhere to. Other yogic texts name abstinence as the surest and speediest way to boost our deepest reserves of vitality and power. And as Piper notes, many other spiritual traditions-including Buddhism and Christianity-incorporate chastity into their codes of conduct. Spiritual luminaries ranging from Mother Teresa to Ramakrishna to Mahatma Gandhi all practiced celibacy for at least some period of their lives. Gandhi went so far as to call life without celibacy “insipid and animal-like.”

But the thought that yogis shouldn’t have sex-or at the very least should rein in their sexual energy-challenges our modern notions about both yoga and sex. We live in a radically different world from that of the ancient yogis who spelled out the discipline’s original precepts. Those yogis lived lives of total renunciation; today, we toss in a Friday yoga class as a prelude to a gourmet meal, a fine wine, and-if we’re lucky-sex for the grand finale. Even though much of yoga is based on ascetic precepts that counsel denial, today the practice is often touted for its ability to improve one’s sex life, not eradicate it-and some people even seem to view yoga classes as prime pick-up spots.

So how do we square time-honored ascetic traditions like brahmacharya with our modern lives? Can we pick and choose among yoga’s practices, adopting those we like and sweeping the trickier ones like brahmacharya under the yoga mat? Or can we fashion a modern reinterpretation of this precept, adhering to the spirit of brahmacharya if not the letter of the ancient law? In other words, can we have our sex and our yoga too?

The Gifts of Abstinence

Ask students at a typical American yoga class if they’re ready for yogic celibacy, and they’ll likely roll their eyes, furrow their brows, or simply laugh at the absurdity of such a question. But according to yoga’s long tradition, celibacy offers potent benefits that far outweigh its difficulties. Abstention is said to free us from earthly distractions so we can devote ourselves more fully to spiritual transcendence. It is said to move us toward a nondual, genderless state that promotes a profound sense of relationship and intimacy with all beings, not just a select few. Celibacy is also said to support the important yogic principles of truth and nonviolence, since promiscuity often leads to secrecy, deceit, anger, and suffering. And it is touted as a way to transform our most primitive instinctual energies into a deeper, brighter vitality that promises good health, great courage, incredible stamina, and a very long life.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika, a key fourteenth-century text, says those who practice brahmacharya need no longer fear death. The Bhagavad Gita names brahmacharya as a fundamental precept for a true yogi. And according to Patanjali‘s Yoga Sutra-a sort of bible for many Western yogis-brahmacharya is a crucial practice that leads to profound vigor, valor, and vitality. Patanjali even says that brahmacharya leads to disgust for the body and for intimate contact with others. “ForPatanjali, brahmacharya has a very strict interpretation-celibacy-to be practiced at all times under all circumstances,” says Georg Feuerstein, founder of the Yoga Research and Education Center in Santa Rosa, California. “For him, there are no excuses.”

A Modern Interpretation

Fortunately for spiritual aspirants who aren’t interested in giving up sex altogether, other ancient yoga texts are a little more lenient in their interpretations. These offer special exceptions for married yoga practitioners, for whom brahmacharya is understood as “chastity at the right time,” Feuerstein says. “In other words, when you’re not with your wife or husband, you practice brahmacharya in body, speech, and mind. It means you abstain from casual sexual contact and casual sexual conversation, like sexual jokes. You are also not supposed to think sexually about the other gender-or the same gender, if that’s your inclination. So you restrict your sexuality to moments of intimacy with your spouse.”

Many of today’s yoga masters have gone even further-indeed, some purists would say, too far-offering a modern interpretation that they say adheres to the intent if not the details of the traditional precept. Today brahmacharya is often interpreted as moderation, monogamy, continence, or restraint. Since the literal translation of brahmacharya is “prayerful conduct,” luminaries including B. K. S. Iyengar and T. K. V. Desikachar say the precept doesn’t necessarily rule out responsible sex. But these teachers also tell us that brahmacharya requires us to carefully consider the relationship between our lives on the yoga mat and our lives under the sheets.

“What brahmacharya means is a deep clarity about sexual energy,” says Judith Hanson Lasater, Ph.D., a San Francisco physical therapist and yoga teacher since 1971 and author of Living Your Yoga (Rodmell, 2000). “First and foremost, it means being aware of your own sexuality, being clear about your feelings and needs at every moment. I don’t think one needs to be celibate in order to progress in yoga and spiritual practice, but I definitely think one has to be very careful and clear about the sexual choices one makes. You’re not going to be a whole healthy person unless you’re whole and healthy in your sexuality.”

Lasater explains that in previous eras, celibacy was the only certain way to prevent parenthood, offering a pragmatic reason to require abstinence among those who devoted themselves to a spiritual path. “In other words, if I’m having a sexual relationship in the time of Patanjali, I’m going to have babies, I’m going to have a family, I’m going to become enmeshed in the world,” she says. “That’s going to change my spiritual practice.”

This is the very motive Mahatma Gandhi offered when he took his first vow of brahmacharya, after marrying and having four children with his wife, Kasturba. Gandhi said fathering and supporting children robbed him of precious energy during a time when he wanted to devote himself more completely to public service. However, over a period of many celibate years-admittedly struggling with the practice and even breaking his vow on several occasions-Gandhi discovered that the benefits of brahmacharya far exceeded birth control. His home life became more “peaceful, sweet, and happy,” he developed a new measure of self-restraint, and he found increasing reserves of time and energy to devote to humanitarian and spiritual pursuits. “I realized that a vow, far from closing the door to real freedom, opened it,” he wrote in his autobiography. “What formerly appeared to me to be extravagant praise of brahmacharya in our religious books seems now, with increasing clearness every day, to be absolutely proper and founded on experience.”

A Spiritual Elixir

Beyond conserving energy, yoga philosophy also describes a more esoteric benefit of celibacy: a sort of alchemical transmutation of base sexual energies into spiritual vigor. According to the ancient Indian science of Ayurveda, semen was considered to be a vital elixir that housed important subtle energies. Ejaculation was said to lead to loss of power, energy, concentration, and even spiritual merit. And conserving it through celibacy and other yoga practices was said to help develop rich stores of this subtle energy, called ojas, thereby building vitality, character, and health.

Feuerstein says he’s witnessed firsthand evidence of celibacy’s power to transmute sex into spirit. He recalls encountering Swami Chidananda, a celibate leader of the Divine Life Society, in India in the late 1960s. “He always seemed to be wearing this beautiful perfume; he always exuded this beautiful scent, very subtle but beautiful,” Feuerstein says. “One day I was curious enough about it to ask my friend who ran the center, ‘What is this perfume he’s wearing?’ She laughed and said, ‘He’s not wearing any perfume! It is because he has mastery of brahmacharya and his body simply uses the hormones differently.’ ”

But what about women? Never fear, Feuerstein says, the same principle of energy transmutation applies-it’s just that until the last century yoga practitioners were almost always male. “People often get confused about this,” he says. “They always think it’s the seminal discharge that’s undesirable, but it’s actually the firing of the nervous system during sexual stimulation. And that applies to both men and women.”

The Four Stages of Life

In orthodox Indian philosophy, brahmacharya means more than just celibacy. It is also the term used to denote the first of the four purusharthas (stages of life) spelled out in ancient Vedic texts. In this tradition, brahmacharya designates the period of studenthood-roughly the first 21 years of life-and during this time celibacy was to be strictly followed in order to keep one focused on study and education.

During the second stage, the grihastha (householder) phase, sexual activity was considered an integral aspect of family building. Abstinence returned as a common practice at age 42 or so, when householders turned inward for the final two stages of life, the vanaprasthya (forest dweller) phase and the sannyasa (renunciate) phase. Yogis and monks were typically the only exception to this pattern, skipping the householder stage altogether and remaining celibate throughout their lives.

Some modern yoga teachers point to the “life stage” approach as an important model not just for the practice of celibacy but also for other practices, interests, and values. According to this model, codes of conduct vary with age. “It’s reasonable to think that celibacy is not a black and white choice,” Lasater says. “There might be periods in your life when you practice it, and others when you do not.”

That’s certainly the way Adrian Piper sees it. She didn’t turn to celibacy until age 36, after a long and active sex life, after marriage and divorce, and after achieving success as both a philosophy professor and a conceptual artist. “I definitely think it’s OK and healthy to abstain at certain times,” she says. “Sex is a lot of work, and negotiating a long-term sexual relationship is even more work. Sometimes it is very important to do that work. But there are some other kinds of work-inner work, creative work, intellectual work, healing work-that it’s sometimes even more important to do, and no one has an infinite amount of time and energy. And sex is so consuming that sometimes it can be really useful to take a time-out to do the inner work of processing the lessons it offers us.”

Piper, who contributed an essay about brahmacharya for the book How We Live Our Yoga(Beacon Press, 2001), says that she was surprised to see how far-reaching the benefits of this practice have been for her. “One of the gifts brahmacharya has given me is the discovery of how much I like men,” she says. “Now that I’m no longer duking it out with them trying to get my needs satisfied, I find that I really enjoy their company. The most amazing part is that this seems to generalize beyond the narrowly sexual sphere to all of my social relationships. My friendships with men-and women-have deepened enormously.

“I believe that Patanjali and others spelled out these principles as guides to help us tune into the deeper parts of the self that are hidden or silenced by the call of our desires and impulses, which are usually so loud that they drown out the signals from these deeper levels,” she adds. “If we don’t realize there’s an alternative to being driven by our desires, we don’t have any choice in how we act. Our culture does a really good job of encouraging us to indulge our desires and ignore any signals beyond them.”

After reaping the benefits of celibacy for nearly two decades, Piper challenges the less stringent modern reinterpretations of brahmacharya. “I think continence, moderation, responsibility, et cetera, are all valid and very important spiritual practices,” she says. “I also think it only creates confusion to interpret all of them as varieties of brahmacharya. The problem with talk about more moderate interpretations of brahmacharya is that it makes practicing brahmacharya in the traditional monastic sense of celibacy sound extreme and radical.”

Still, Piper is quick to admit that celibacy isn’t for everyone. In her case brahmacharya evolved naturally out of her spiritual practice; in fact, she never actually took a formal vow. Rather, she explains, brahmacharya chose her. “I think being able to say to oneself simply and clearly that brahmacharya is not appropriate for one’s particular circumstances shows a lot of self-knowledge and spiritual maturity,” she says. “I would recommend trying brahmacharya to anyone who feels like trying it, but I would not recommend it to anyone who finds it really difficult. From what I’ve seen, making a vow to practice brahmacharya is practically asking for some gigantic tidal wave of sexual desire to come rolling in and toss you out to sea.”

And that’s exactly what critics of strict celibacy say is the problem with it: Denying such a primal instinct is just asking for trouble. The recent revelations of sexual misconduct and subsequent cover-ups in the Catholic Church are only the latest, most visible evidence of sex in supposed bastions of celibacy.

Many spiritual traditions-from Christianity to Hindu yoga to Buddhism-have been ripped by scandal when spiritual leaders preached chastity to their followers and yet secretly sought out sex, often in ways that produced heartache and trauma for everyone involved. As Feuerstein sees it, “The ascetic variety of brahmacharya is pretty much out of the question for most people, for 99.9 percent of us. Even those who want to do it, I feel, are by and large incapable. If sexual energy doesn’t come out one way, it comes out some other way, often manifesting in negative forms.”

Celibacy’s Dark Side

Residents of the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health in Lenox, Massachusetts, have had firsthand experience with the perils and pitfalls of celibacy. For its first 20 years, all Kripalu residents-even married ones-aspired to practice strict brahmacharya. While preaching such celibacy to his disciples, however, Kripalu founder Amrit Desai secretly solicited sex from a number of his female students. And Desai’s behavior, when it finally came to light, sent the organization into a massive tailspin and a period of deep soul searching. Desai was asked to leave Kripalu, and the organization carefully reconsidered its attitudes toward sex, celibacy, and brahmacharya.

“In the early days we were so focused on celibacy-we held it as such a central value-that we created a charge around it,” says Richard Faulds, chair of Kripalu’s Board of Trustees and a senior teacher. “Brahmacharya was overemphasized, and to the extent that we enforced it as a lifestyle, we created dysfunction. People have a tendency, when they’re having such a basic urge denied, to express it in some other, less-than-straightforward, inappropriate ways.”

As a result, today only new arrivals to Kripalu’s resident program are required to practice celibacy, and they are only encouraged to continue the practice for a maximum of two years. “Celibacy really helps people heal and become physically vibrant, and it also shows you all of your dependencies,” Faulds says. “We’ve found if people practice celibacy for a year or so, they really strengthen their sense of self. But our experience, looking back, is that celibacy is not a healthy long-term lifestyle for most people.”

For all but the incoming residents, today Kripalu offers a more moderate-and some would say more manageable-vision of brahmacharya: a regular yoga practice, a wholesome lifestyle, and moderation in sensory pleasures, especially food and sex.

“Yoga is about building your energy and awareness so it leads you in a spiritual direction, and for most people, healthy and natural sex is not an obstacle to that,” Faulds explains. “Sexual energy has to be awakened, because if it’s not awakened, there’s a lot of subconscious denial and repression that keeps you from being fully alive. What happens for many of us, especially in our society, is that the mind arouses the body in an obsessive way-for tension release, for approval seeking, for distraction, and just for fun. That’s where it depletes your energy.

“There’s nothing wrong with responsible sex; it’s not a bad thing,” he adds. “Yoga is not making a moral statement with its teachings on brahmacharya; I think it’s very important to realize that. But yoga is saying that you will have more pleasure and bliss in the long run through moderation and through channeling a portion of your sexual energy into spiritual growth and meditation.”

What’s a Yogi to Do?

So what does brahmacharya in action mean today? For some like Piper, it means exactly what Patanjali said: total abstinence. For others, brahmacharya means practicing celibacy only during certain times-at a relationship’s end in order to recover, during a yoga retreat in order to focus more clearly, or perhaps when one’s practice is particularly deep and celibacy naturally evolves out of it. For still others, brahmacharya means merely refraining from suggestive speech or promiscuous behavior, or at the very least taking note of how much time and energy we and our culture devote to sex-sex as marketing tool, sex as conquest, sex as distraction, and sex as jackpot.

“There’s nothing wrong with the radical version of brahmacharya, except that we may not be up to it,” Feuerstein says. “So then we modify, depending on our capacity. I think we should make every attempt to economize our sexual impulses: If we have a partner, we confine our sexuality to that partner instead of driving it all over the place and becoming promiscuous. Especially if we are teachers-and I know teachers who are failing at this miserably-then we make every attempt not to do that with our students. Brahmacharya has to become at least an ideal. Even if we fail, we should not indulge in feelings of guilt; instead, we should just try to hold that ideal as something to aspire to. If the ideal is not there, well, then we are at a lower level of the game.”

Feuerstein thinks it’s possible to more deeply explore brahmacharya without necessarily becoming a monk. He suggests experimenting with a short period of celibacy-a week, a month, a year-to observe its transformative power, or at the very least to learn about the fierce grip that sexual thoughts, words, and actions have upon our consciousness. “I did it myself at one point in time, and it’s an amazingly instructional practice,” Feuerstein says. “It offers a wonderful sense of freedom and-apart from the agony-it’s very liberating. It’s a superb exercise.

“Every time we get out of a habitual groove, we are training the mind, we are channeling the mind’s energy in a more benign manner,” he adds. “And that’s really the purpose of all these yoga practices: to discipline the mind so that we are not driven by our biological or unconscious nature. We become mindful, and in that way we can attain great self-knowledge and also this wonderful thing we call self-transcendence.”

For Lasater, it’s not just our actions but also our attitudes behind them that really matter. “I could become a nun and lead a celibate life and still not have clarity about sexuality,” she says. “Or I could even run from sexuality by being promiscuous. But what is considered promiscuous to my grandmother and what’s promiscuous to my daughter might be completely different things. So it’s not the action; it’s the clarity.

“Brahmacharya is not an answer; it’s a question,” Lasater adds. “And the question is, How will I use my sexuality in a way that honors my divinity and the divinity of others?”

Claudia Cummins lives, writes, and teaches yoga from her home in Mansfield, Ohio. To maintain her balance while writing this article, she read both The History of Celibacy and Lady Chatterley’s Lover.